We’ve constructed a ruthless exam system where bereavement barely matters

I met a woman on a train last week who told me about her two sons currently sitting their GCSEs and A-levels. Stressed teens are difficult to live with, so I commiserated with her. But these teens have it worse than most, she explained: their father died last November. Astonishingly, she told me: “The exam boards can take it into account and give you up to 5% extra marks. But the bereavement has to be within the past six months.” She looked painfully sad for a moment. “Apparently he died two weeks too early.”

Related: A century of adult education has been tossed aside – is it too late to rescue it? | Laura McInerney

I Googled, hoping she was wrong, but found she was heartbreakingly correct. I discovered a misery rate card, published each year by the Joint Council of Qualifications. Severe bodily injury at the time of examination gives you 4% extra marks. Physical assault before the exam is 3%. Minor ailments (such as hayfever): 1%.

Exam boards try to be fair. Every year, special consideration is applied for in more than half a million GCSE and A-level exams, and the vast majority are accepted. In my time as a teacher I saw pupils taken out of exams by illness, accidents, even one stuck in an armed hold-up. (Witnessing a distressing event: 3%). Death of a family member provides the highest boost but the rules are harsh: “recent” grief can last four months.

Evidence that death has a lengthy impact on GCSE results is strong. A study in 2004 found that bereaved young people scored on average half a grade below expectation in each exam. A Swedish national cohortstudy found that parental death lowered grades even when controlling for just about every other imaginable factor, including socio-economics, criminality, and parental mental health. And this has a lasting impact, with a recent Danish study finding that bereaved males were up to 26% less likely to get degrees than their peers.

Related: No other European country tests children at 16: let’s scrap pointless GCSEs | Sandra Leaton Gray

Yet, despite this evidence, there is no official support for children who suffer bereavement. At secondary school, most teachers have no idea if a child has lost a parent – and there’s not much they can do if they have. As a sixth-form manager I remember giving one pupil a hard time about her grades, when she noted that her mum had died the year before. “Can’t you give me a break?” she shouted. The answer, sadly, was no. Six months later she would leave our school. I couldn’t bring her mum back but what I could do was push her to get into university, which would help her get the graduate job she wanted, and the life she craved.

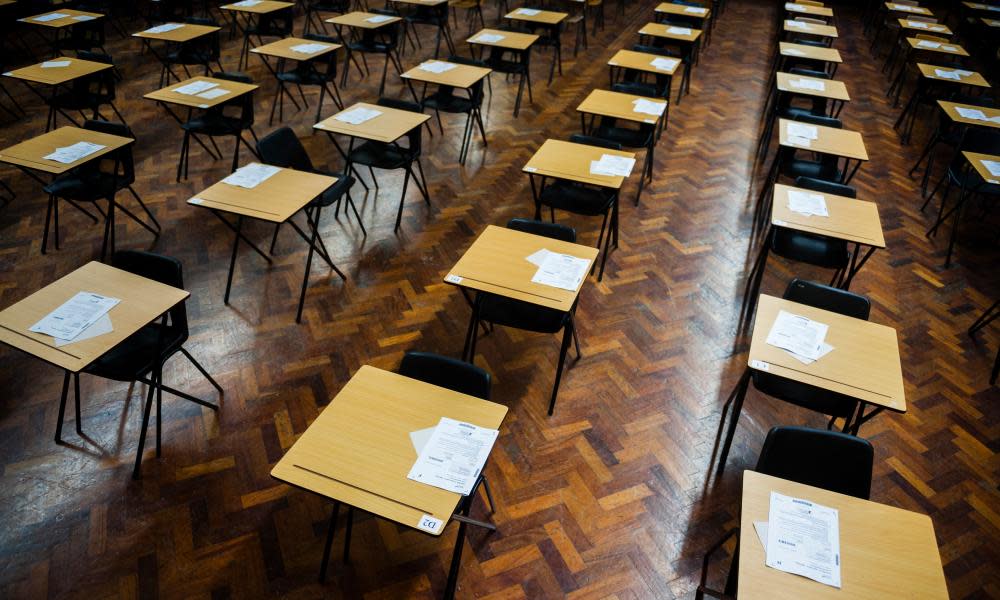

She had one shot. Almost no one gets to resit their GCSEs, other than English and maths, and A-level resits have patchy availability. We’ve in effect constructed a system that relies on young people being perfectly poised in the summers when they are 16 and 18, to give their best performance. In the past, a setback could be overcome through night school or the Open University, but with these options now more limited and more expensive, not being ready on a random day in June is potentially disastrous.

Related: Stress and serious anxiety: how the new GCSE is affecting mental health

People looking for easy answers might call for the scrapping of GCSEs, or the resurrection of modular exams. Frankly, I don’t think either solution helps. But I do wish exam boards would create ways to bump up results. Universities offer immediate resits each summer, why not for GCSEs and A-levels? Or allow people to continue resitting exams as they get older? If exams were online, each candidate could receive questions relating to the syllabus they studied and have them auto-marked. If you’re doing better at history by age 21, why not have this reflected in updated scores?

Ultimately, it would take imagination to implement these ideas, but it seems a kinder, more positive solution than the current algorithms of despair.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News