How the Waco inferno lit the flames of dissent among today’s radical right

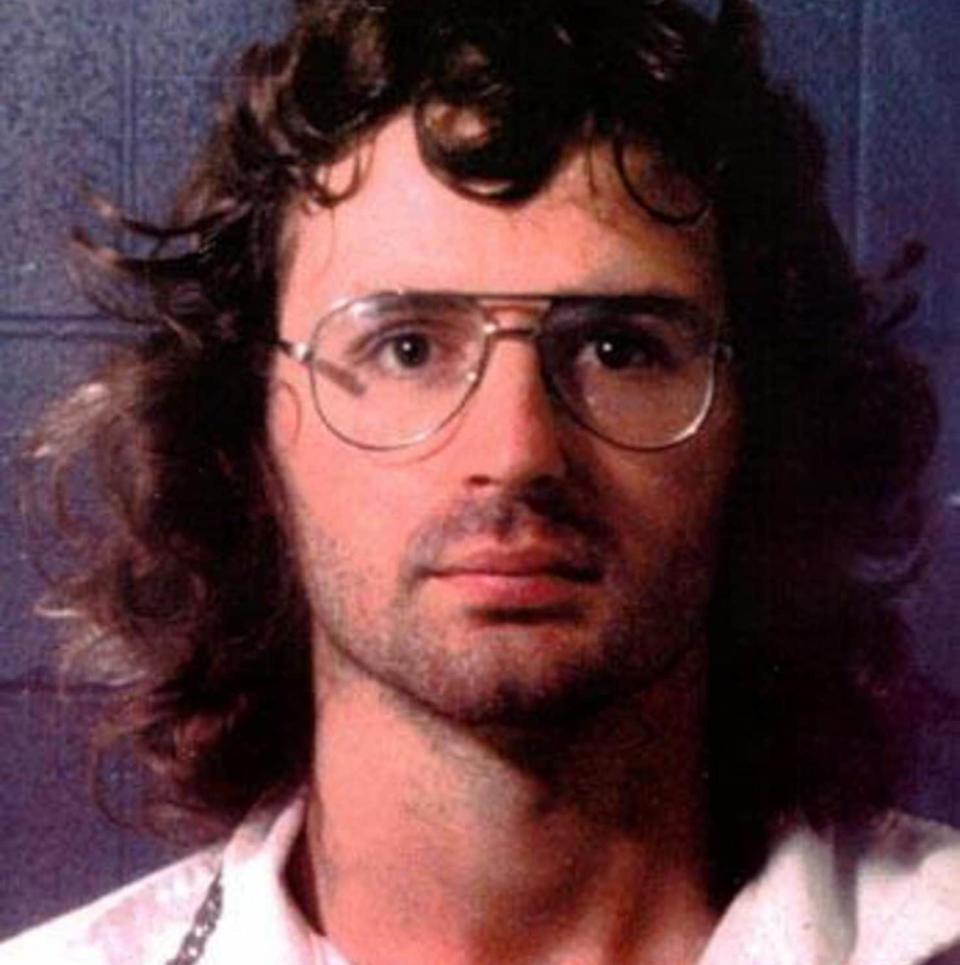

It was 19 April 1993. A fire had erupted at the Branch Davidian compound just outside Waco, Texas, killing 72 men, women and children. I was living in New York at the time, working evening shifts as a proofreader, which gave me plenty of free time to watch the eerie drama of the blaze, as well as the 51 days of FBI siege that preceded it, unfold on CNN.

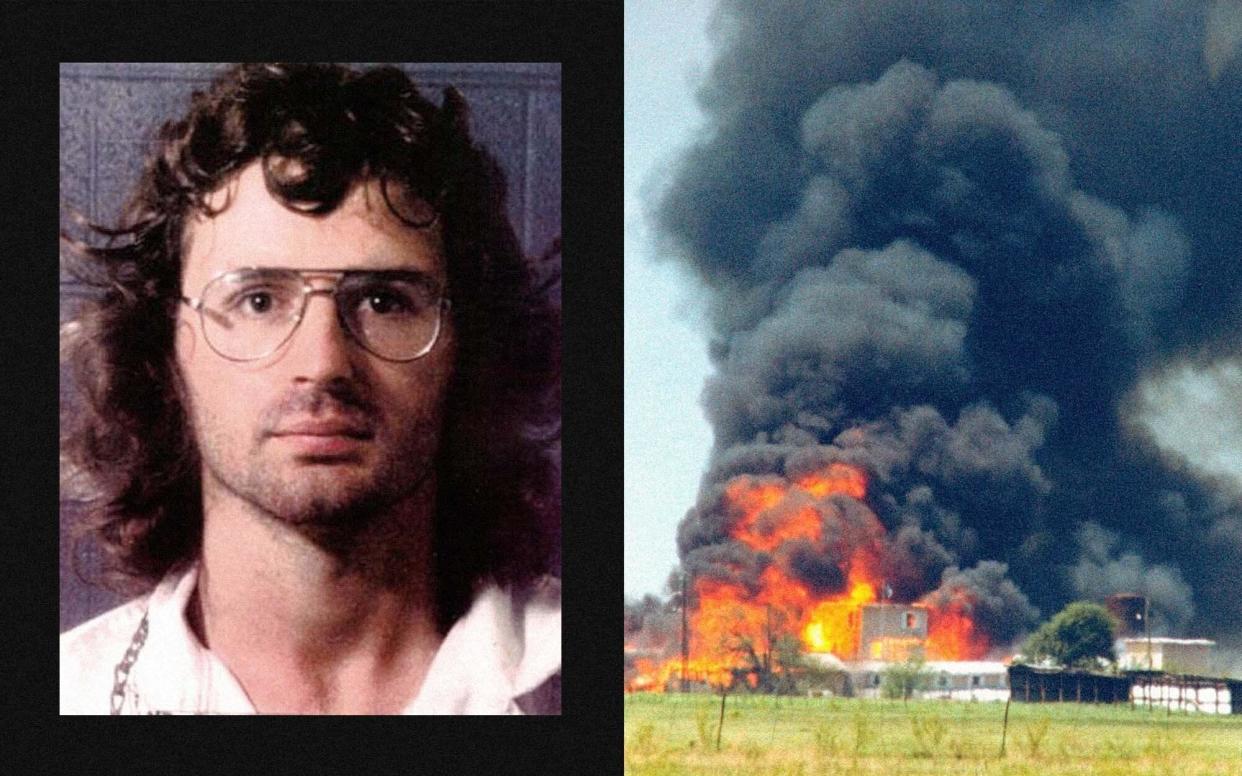

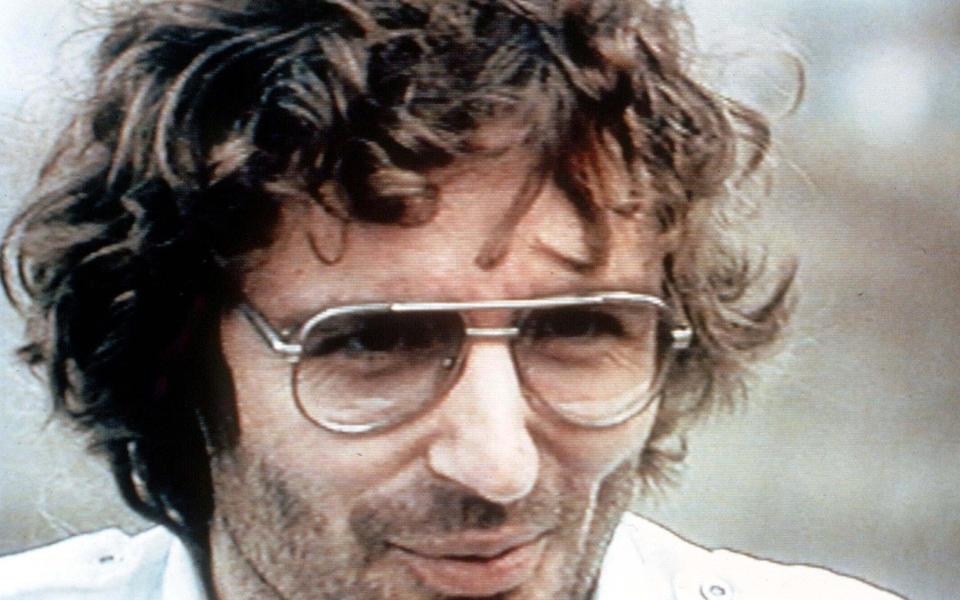

The compound had been occupied by the cult leader David Koresh and his followers. Koresh was accused of possessing a menacing cache of illegal weapons, and there had been reports he was sexually abusing young girls. This prompted a federal raid, which went badly wrong, resulting in the deaths of multiple Davidians and four federal agents.

Seven weeks on and the fire had ended the siege, but as I stared at the smoking pit where the Branch Davidian compound used to be, I felt unsettled. I didn’t really understand what had occurred at Waco. Perhaps it had been the inability even to spot a person in the window of the compound, to put a face to the enigmatic Branch Davidians, but the mystery ate at me. What had brought David Koresh – a self-proclaimed messiah – and the United States government into a lethal conflict?

So, three years ago, I began working on a book about the notorious Koresh and his road to Waco. I interviewed dozens of Koresh’s family and childhood friends, his followers, defectors, Department of Justice officials, agents from the FBI and ATF (Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives), and many others. What I heard repeatedly from people on both sides of the issue was that the tragedy had foretold things even darker than the blackened ruins in Waco.

For the far Right, Waco made a secret world, one of government oppression and tyranny, visible for the first time. ‘Waco became a door,’ wrote one poster on a Right-wing website soon after the tragedy ‘and a finger of God for the nation’. The conspiratorial Right not only gained a set of martyrs in Koresh and his followers; the reputations of its enemies, especially the federal government, were tarnished. Listening to the hundreds of hours of negotiation tapes that Koresh and others recorded with the FBI, I was shocked at how often Koresh’s lieutenants mentioned conspiracy theories about the Illuminati or the Council of Foreign Relations. It was as if they were already tuned to the future.

A year after the fire, the first major militia sprang up in Michigan. Many more such outfits followed. And they didn’t merely lie in wait. In the early ’90s, the FBI was opening about a hundred domestic terrorism cases a year. At the end of the decade, it was 10 times that. By the mid-’90s, militias were operating in every state in the union, with as many as 250,000 total members. Because of Waco, millions were introduced to a world where conspiracies grew like wild bamboo. Ordinary people – your mailman, your doctor, your husband or daughter – learned that America was being corrupted and sold to evil forces.

One thing strikes me about the two groups, the Davidians and the far Right. All his life, Koresh refused to accept the judgment of others; he refused to accept anything that didn’t exalt his own existence. In his need to be celebrated, Koresh created a place in his own mind where he could live with some degree of self-love. That place sustained him for years.

In talking with the men and women who believe Koresh was a martyr for their cause, I found they often do the same thing. They privilege their own imaginations over real things. They see portents and signs of the government’s despotism in small, everyday happenings. They tend the narcissist within and seek out leaders who are egotists themselves, and who are capable of this same kind of fabulous world-building. The conspiracy theories are often ancient, but the way their believers seem to live inside of them is something new.

Koresh’s followers looked on their leader as a kind-hearted prophet, when the truth was he’d become a dark, menacing figure, berating and raping his followers as he preached the coming joys of Armegeddon. But what made Koresh like this? Where did he come from?

After spending weeks in his native Texas, talking with his family and high-school buddies and listening to hour after hour of his lectures, it was clear to me that his peculiar obsessions could be traced back to his disastrous childhood. I found, too, that it was the men in his life who failed him. Over and over again, Koresh – born Vernon Wayne Howell in 1959, a name he kept until he restyled himself David Koresh in 1990 – tried to get close to his real father, his stepfather, his grandfather and a handful of older male authority figures. Each time, he walked away rejected and often humiliated.

Koresh’s stepfather Roy Haldeman was a key offender. Koresh’s real father, Bobby Howell, had disappeared from his life early on, and he’d lived with Haldeman from around age four. According to sources and Koresh’s own account, which he shared with several of the people I spoke to, Haldeman belittled Koresh, whipped him with belts and branches, and mocked him for not being manly enough – although Haldeman denied Koresh grew up in an abusive household. The sources add that his mother beat him in front of his friends; and that bigger boys sexually assaulted Koresh, as did a member of his mother’s family.

The school bullies targeted Koresh almost from day one. Not only was he in the ‘slow class’, a result of a learning disability, but he was shy. His large, metal-rimmed glasses didn’t help. Whenever he’d try to play basketball or climb on the swings in the schoolyard, the kids would gather around, chanting, ‘Retard, retard,’ or, ‘Four eyes.’ After third grade, they switched to ‘Mr Retardo’, which stuck for years.

The way Koresh’s aunt Sharon and the rest of his family described his early days to me, life carved a deep hole inside him, and the only thing big enough to fill it, the only thing that would match his grandiose need for deliverance, was God.

The young Koresh started spending a lot of time praying out in the barn. He’d stay there until dinnertime some nights, praying. Koresh’s half-brother Roger found this bizarre. Sometimes he’d leave Koresh kneeling by the side of his bed, his hands folded, and come back eight or 10 hours later and find him still there in the exact same position. It was like a magic trick. Had he even gotten up to pee? For Koresh, God loved him like no one else did.

When he was in his late teens, Koresh went off on his own, hoping to meet a great destiny. In Tyler, Texas, he met Sandy, the daughter of the preacher at the local Seventh Day Adventist Church. He fell for her.

Sandy gave me the first extended interviews she’s done in 30 years. She’d spent decades fleeing her connection with Koresh, and was terrified of being targeted again. But over many weeks, I was able to gain her trust. And the details she provided of this missing period in Koresh’s life were crucial. They showed that, even as he found love and was filled with plans for the future, Koresh was unsatisfied. Or unsatisfiable. He craved more control over himself and others. He even began to have visions of his own.

Sandy quickly realised her new boyfriend had a fanatic streak. He told her God was speaking to him. But those visions were curiously tailored to what Koresh himself wanted. More than once, Sandy told him, ‘Just because you have a dream doesn’t mean the Lord is talking to you.’ Koresh only scoffed. And when Sandy grew distant, he stalked her and even tried to kidnap her in his trunk. (He always hated the idea of people leaving him.)

In the summer of 1981, after Sandy had rejected his demands to run away with him, a shattered Koresh headed for Waco, Texas, where a fellow Adventist had told him there was a sect who were preaching the coming end of the world. There, at the Mount Carmel compound, Koresh found two things: an obscure Christian sect looking for a prophet, and a place that would feed his desire to manipulate women, to possess them wholly.

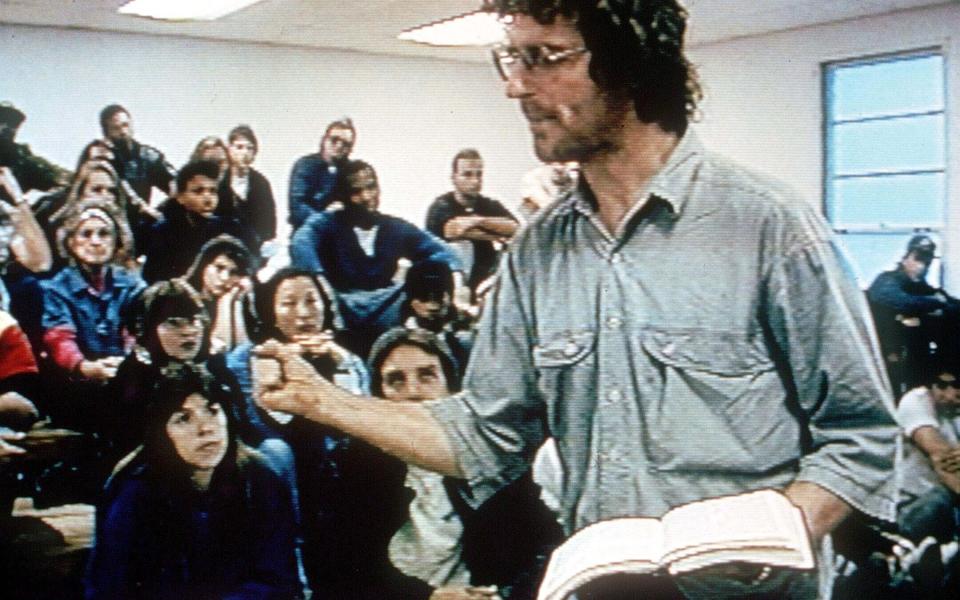

For two years, Koresh listened and studied. He became a kind of handy-man, fixing things around the compound. He learned Branch Davidian theology. And then he was given permission to deliver his first Bible study.

At first, Koresh was tentative, hard to hear from the back of the room. But he soon grew more confident. After a few months, the rhythms of his talks carried the Davidians along as if they were sweeping forward on an ocean wave, up and down until they began to feel almost dizzy. People fell to their knees right there in the chapel.

His star rising, Koresh met Rachel Jones, just 14. After pursuing her for months, in the middle of a winter’s night in early 1984, he went to her bedroom and shook her awake. ‘Rachel, you’re going to be my wife, OK?’ he said. ‘But don’t be afraid, we’re gonna just be married in name only.’ Rachel agreed. They went to the courthouse and got their marriage licence. When they were officially husband and wife, Koresh took Rachel back to a blue Chevy van he’d parked nearby. He told Rachel to get into the back. Those who knew Rachel – who would go on to die in the fire – said it was then that he raped her for the first time, breaking his vow to her before it was a day old.

The pattern deepened over the next few years. Koresh groomed and seduced dozens of girls and young women, and fathered a brood of young children he preached would become the judges and rulers of God’s new kingdom. As time passed, Koresh desired younger and younger girls.

It caused him to spiral into self-loathing and depression. It was as if there were two Koreshes, fighting for control. But whenever he had a crisis of confidence, it was always the darker side of his personality that emerged stronger.

Koresh did set up some guardrails to protect young girls, but they only emphasised just how all-encompassing his paedophilia had become. He decreed that the Davidian men shouldn’t change the diapers of their baby daughters, lest they be tempted. His reason: once, when he was changing his own infant daughter, he’d become aroused. Koresh imagined this was a common response, and so he forbade men from being around naked infants.

Koresh had started out as a young man with deep psychological wounds who wanted to heal the world. By the early ’90s, however, he was a seductive, manipulative figure who’d recreated the world of his childhood – of rules and beatings, of sexual abuse and terror – on a much larger scale, then set himself to rule over it.

He grew increasingly suspicious of the outside world, said God had told him to start building an army to fight in the coming Armageddon, and began to exercise strict control over his followers, including their romantic choices. In 1990, he declared that all the women in the compound belonged to him. All the married men had to give up their wives and pretend their children belonged to others. Couples wept together as Koresh explained the teaching.

Koresh tested his followers constantly. Stepping out of line could mean a beating with a fence paling or getting locked inside a small cabin and raped, which happened to one female follower. The children had it even harder than the adults. If a child displeased Koresh, they were spanked, often violently. Koresh would be set off by a variety of things: a sour glance, crying, backtalk. If a child accidentally spilled a drink or knocked over a plate, they would often turn their head and crouch, face near the floor, anticipating a blow. David’s own children weren’t exempt from the abuse; in fact, I learned from affidavits signed by his Australian followers that he subjected his son Cyrus to terrible, sustained beatings and psychological torment that far outstripped anything that Koresh had suffered in his boyhood.

Those followers who wouldn’t accept his new teachings were pressured to leave, or they were banished. It was a total erasure: their families were told to even throw away photos of their loved ones. David – who had, he proclaimed, renamed himself after the biblical ‘god of life and death’ – decreed that to question him in any way was to question God himself.

In 1992, hand-grenade casings, discovered by a vigilant UPS driver, tipped off the authorities that something untoward was happening at the compound. The ATF was assigned the case, and surveillance of Mount Carmel began in January 1993. ATF agents, pretending to be local college students, set up their watch in a house across from the compound.

The planning of the raid was erratic. Among other missteps, the surveillance team failed to detect Koresh’s frequent trips into Waco, where he could have been arrested. The plan was a case study in how your government can kill you. It wasn’t a jack-booted conspiracy; far more mundane factors – mismanagement, hubris, sheer laziness – led to the disaster at Waco. The ATF planners created a hugely dangerous mission that was almost bound to go wrong.

The raid went off on 28 February 1993 and negotiations began even before the gunfire died down. The FBI, ordered in by President Bill Clinton, took over the scene, and a long, hallucinatory debate began: David Koresh vs the USA. A lone telephone line snaked its way from the negotiators’ headquarters at an air base miles away to where Koresh lay in a dirty T-shirt and jeans. The two sides spoke for many hours, on subjects sacred and profane. There were times when their talks seemed more like therapy than negotiations. Koresh’s mind roamed back to his childhood, his family life, schooldays.

His mood could turn easily, the FBI found. At times, he seemed to want to befriend the negotiators, guys mostly in their 30s and 40s. In his drawling voice, he even told them he loved them. He had an old-boy charm about him that could work on your mind.

But Koresh was all over the map: screaming in rage one moment, chuckling the next. When he was introduced to one FBI negotiator, Byron Sage, he drawled, ‘Agent Sage, have you ever heard a person die?’

Calm as could be. As if they were sitting in the park playing checkers, Sage thought. ‘Yes, I have,’ Sage said.

‘Then you know how to pronounce my name.’

Sage didn’t understand. ‘What do you mean by that?’

‘It’s pronounced like that last breath of someone dying. Kor-essssshhhhhhh.’

Sage felt the hair on the back of his neck rise.

The FBI negotiated the release of dozens of men, women and children away from Koresh’s control over the course of those seven weeks, during which the world’s media remained transfixed on the ongoing siege. The situation inside was dire, with food and water supplies running out. But on 19 April, in an effort to end the siege, the FBI decided to move in on the Davidians. Specially adapted armoured vehicles punched holes in the side of the buildings and inserted tear gas. Soon, it was everywhere.

Inside, Koresh’s longtime follower Clive Doyle – who would be one of just nine Davidians to survive the fire – was in the chapel. He could hear the crying of children from the concrete bunker that sat under the tower in the middle of the compound. The tear gas powder had got on their skin and they were scratching at their arms, whimpering with pain. Although many of the adults had gas masks, there were none for the kids so Davidian mothers and fathers in the concrete bunker grabbed towels and stuck them in buckets of water. Then they held the drenched cloths to their children’s faces.

Around midday, a fire was lit by the Davidians in pre-planned spots around the compound. One family huddled together, seven of them. As they expired from the gasses released by the fire, their bodies fell forward, until they were found in a clump of entangled limbs. On the second floor, just below the tower, a number of Davidians were found together. They were carrying handguns and bayonets. As the fumes overcame them, they dropped the weapons at their feet.

The victims of Waco are testament to Koresh’s bitter manipulations. It was he and he alone who built the road to the deaths at Waco. But in almost every other American tragedy, from Pearl Harbor to 9/11, a hero was eventually found amidst the darkness, a man or woman who expressed the idea that the country was not and never would be dominated by events, no matter how awful.

Waco, it turns out, was different. It was a vision of America so dark that no hero at all emerged from it. None was even created, nor even proposed. Perhaps that’s a sign that the event isn’t truly over. We remember the smoking hole that the debris collapsed into, and we wait uneasily to see what else will crawl out of it.

Koresh: The True Story of David Koresh and the Tragedy at Waco, by Stephan Talty, is published on 6 April by Head of Zeus at £25. Pre-order at books.telegraph.co.uk

Yahoo News

Yahoo News