Why animal activists want to cancel the RSPCA

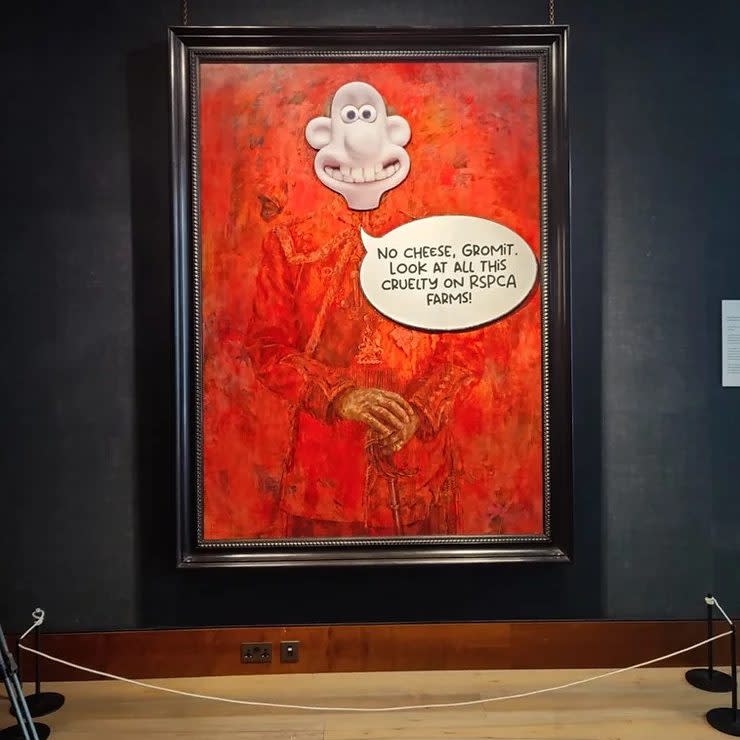

When two activists defaced the King’s portrait in a London gallery this week, it wasn’t in outrage over Big Oil for once.

A picture of Wallace from Wallace and Gromit was stuck on top of his stately shoulders with a speech bubble reading, “No cheese, Gromit. Look at all this cruelty on RSPCA farms!”

The King is the Royal Patron of the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, which runs an accreditation scheme known as RSPCA Assured that “charges hatcheries, farms, hauliers and abattoirs an annual membership fee”.

This week’s stunt follows the publication of an investigation by campaigning organisation Animal Rising into 45 farms signed up to the scheme in which it alleged animal cruelty and suffering at every one as well as 280 legal breaches across the farms.

Activists accused the RSPCA of being happy to rubber-stamp cruelty on factory farms and industrial animal abuse, while naturalist Chris Packham, president of the RSPCA, called on the charity to immediately suspend the scheme.

On Saturday, a different animal rights organisation, Animal Justice Project, which has led similar investigations into the RSPCA Assured scheme, held a protest outside the charity’s headquarters in Horsham, West Sussex. Its activists delivered a cake carrying the message: “DROP RSPCA ASSURED.”

It has cast a shadow over celebrations for the charity which marks its 200-year anniversary on Sunday. The RSPCA was founded on 16 June 1824 when a small group of people met in a London coffee shop, determined to change animals’ lives. Instead of lauding its numerous achievements, the RSPCA has been forced to release a statement saying: “RSPCA Assured is acting swiftly to look into these allegations [...] Any concerns about welfare on RSPCA Assured certified farms are taken extremely seriously.”

While livestock producers are used to being the target of animal activists, for an organisation that was set up to improve the welfare of animals, this will feel like a shot to the very heart of its mission.

The criticisms come just two months after the RSPCA sought to assert its identity as a body that cares for all of Mother Nature’s creatures, not just cats and dogs, by releasing an advertising campaign featuring spiders and snails being saved from harm.

The rebrand infuriated farmers and long-term donors who accused the organisation of woke pandering. It certainly appeared to be an attempt to align the RSPCA with more hardline animal activist groups such as PETA.

Now it seems the organisation’s bluff has been called. Does the RSPCA stand against any kind of harm for all animals, as the activists would have it, or does it seek simply to mitigate the suffering of those that we will eventually slaughter?

“The Assured scheme flies in the face of everything the RSPCA should stand for,” says Animal Rising spokesperson Nathan McGovern. “In the past, RSPCA members have died breaking up illegal animal sports, and their work for cats and dogs has been exemplary, it’s time to extend that to other animals across Britain.”

At the heart of the controversy is the RSPCA Assured scheme which, in 2022, covered more than 24 million UK animals, or 11.67 per cent of the total recorded by Defra. In the view of McGovern and his fellow activists, the RSPCA should not be putting its stamp of approval on farm animals: “The world’s oldest and most respected animal charity needs to be leading the way on protecting animals – not contributing to their suffering.”

Originally called Freedom Food, the scheme was founded in 1994. After a rebrand in 2015 to RSPCA Assured, this year it turns 30 years old. The scheme has about 4,000 members, including hauliers and abattoirs, as well as farms.

In 2021, an independent review of RSPCA Assured found it was making a “positive and significant impact on improving the lives of 136 million animals a year in the UK”.

It has succeeded in raising baseline standards for animal farming in the UK, says Anthony Field, head of UK Compassion in World Farming, an animal welfare lobby group; encouraging producers to provide better living conditions for farmed animals, such as keeping them in cage-free environments, using healthier breeds or providing them with more space and enrichment. “This surpasses UK legal standards where cages, fast-growing breeds or extreme crowding sadly result in poor welfare,” says Field.

Campaigners have also accused the charity of “greenwashing”. Salmon farms, in particular, are in the spotlight for gaining accredited status amid growing concerns over industry methods and animal welfare. Almost 100 per cent of Scottish farmed salmon is produced under the RSPCA Assured scheme.

Rachel Mulrenan, Scotland director of WildFish, a charity campaigning for wild fish and their environment, said that “the requirements of the scheme were not as stringent as consumers might reasonably expect (sometimes not going beyond national regulation), and that there was little, or no, enforcement of these standards if breached.”

Membership costs for RSPCA Assured are based on the size and type of operation. In addition to charging farms, hatcheries, hauliers and abattoirs an annual membership fee to cover the cost of carrying out assessments, the RSPCA takes a licence fee from food manufacturers to use the RSPCA Assured label. “These fees are reinvested back into the scheme to cover running costs […] and bring about welfare improvements, and not taken as profit,” says a spokesperson for the charity. Total income from the scheme in 2022 was £5,298,631. After expenditure, the RSPCA was able to move £1,012,699 in funds “to promote higher animal welfare, conduct research and improve the lives of farm animals”.

For other animal welfare charities, this represents a clear conflict of interest.

Still, for those involved in farming and agriculture, there is no doubt that we should be welcoming and encouraging schemes that support and promote the highest quality of animal welfare when it comes to livestock farming.

“Given the vast bulk of the British public eats meat and dairy as part of their diet, this is an important and valued consideration for consumers,” says Mo Metcalf-Fisher, external affairs director for the Countryside Alliance.

There are an estimated 2.5 million vegans in the UK (4.7 per cent of the adult population), meaning animal farming is a reality of our food system. As such the RSPCA is an important bulwark for the meat-eating majority.

Indeed, not all animal welfare groups want to see an end to RSPCA Assured.

Of the one billion chickens raised each year in the UK, the vast majority are indoor-reared birds. Most of these are fast-growing breeds (known as Frankenchickens) that often spend their final days in agony because their bodies can’t cope with the extreme growth rate. “Slower growing chickens, on the other hand, experience over 50 per cent less pain throughout their lives on average,” says Connor Jackson, CEO & founder of Open Cages, a British animal advocacy organisation.

Farms that use slower-growing chickens, such as RSPCA Assured members, still make up only a very very small percentage of the total. However, these birds command a higher price in the supermarkets; Sainsbury’s sells an ordinary British fresh medium whole chicken (1.6kg) for £4.95, while the closest RSPCA Assured equivalent, a corn-fed whole British chicken (1.55kg), costs £8.85.

“So I believe that improved welfare schemes like RSPCA Assured – whilst far from perfect – serve an important role in incentivising and encouraging the industry to move away from practices like this in order to reduce the massive scale of animal suffering within animal agriculture.“

Animal Justice Project however wants the RSPCA to drop RSPCA Assured: “[It] perpetuates animal exploitation and cruelty, misleading consumers into feeling good about their purchases,” says Claire Palmer, founder and director of Animal Justice Project.

In a meat-eating society, the RSPCA is in an unenviable position. Does it make perfect the enemy of good, or aim to protect what animals it can and incur the wrath of animal activists?

“It seems bizarre that any group describing itself as being pro-animal welfare wouldn’t want such a scheme, unless of course, their true motive was to push a plant-based only eating agenda,” says Metcalf-Fisher.

Palmer makes no pretence of disguising this: “We believe that the RSPCA should not operate an assurance scheme, as animal suffering and exploitation are inevitable in farming. Instead, the RSPCA should advocate for plant-based farming, helping farmers transition and promoting veganism.”

Regardless, the RSPCA’s failure to uphold its standards leaves those consumers who do seek to make better welfare choices in a quandary.

“To be worth anything, animal welfare assurance schemes must ensure they live up to their claims,” says Jackson: “They hold an immense amount of power over the public’s attitudes and purchasing habits, and thus they have an immense amount of responsibility.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News