A woman unmasked her catfisher after finding 2 more victims. They were surprised to find the catfisher's true identity.

Anna Akbari fell for a man on a dating site. They never met in person as he kept canceling.

She challenged him seven weeks after they met when she became suspicious about his identity.

Akbari, who has now written a book, was catfished. She met other victims, and they got to the truth.

Scrolling through the profiles on OkCupid, Anna Akbari was drawn to a man who seemed handsome, witty, and highly intelligent.

The pair connected via Gchat and email. They'd write to each other for hours — often throughout the night — discussing everything from their past relationships, families, and careers to the state of the economy.

Soon, Akbari fell for her admirer — Ethan Schuman, who claimed to be a 35-year-old graduate of Columbia University and MIT — and the pair arranged to meet in person.

But they never did. Every time they made a date, Schuman canceled at the last minute for health, weather, or work reasons.

Her suspicions were raised; she did some detective work and found that Schuman was not who he said he was. He was a catfisher — a person who fakes their online identity to trick victims into thinking they are someone else.

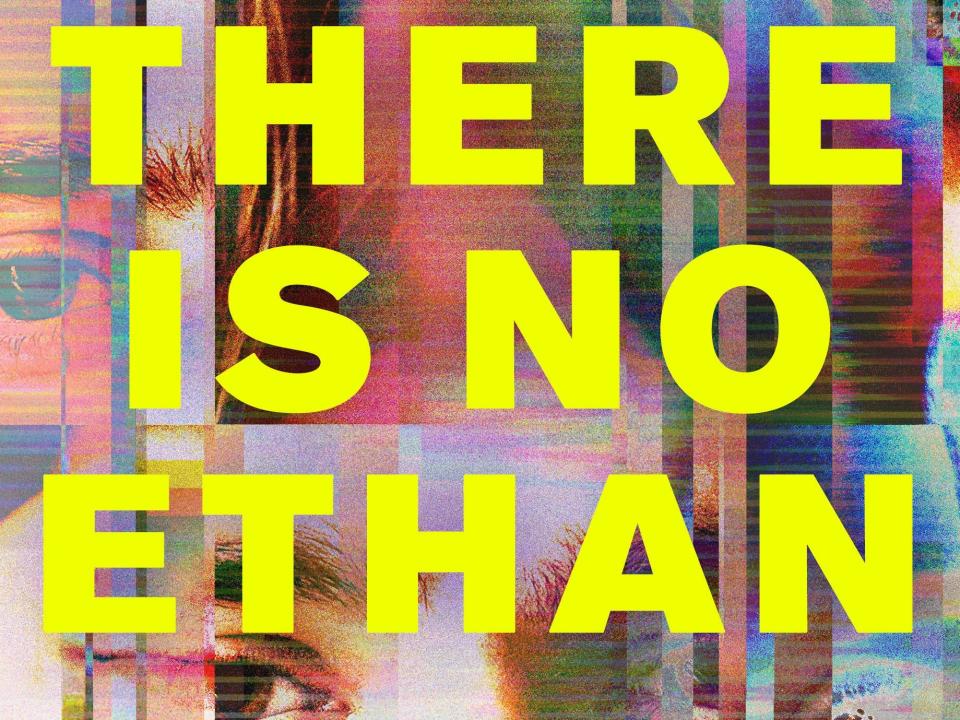

Akbari's new book, "There Is No Ethan," chronicles her traumatic experience. It tells how she was taken in but discovered he was too good to be true. She then tracked down two of his other targets.

The conversations were flirtatious

When she met Schuman in December 2010, the former professor at New York University told BI that she wanted a meaningful relationship.

"He made it clear that he was looking for something real," she told Business Insider. "It sounded very promising and exciting."

She said they typed lengthy emails or did instant messaging.

"Gchat was popular because texting on phones wasn't as ubiquitous as it is today, " Akbari added. "It was easier to use your computer."

The pair exchanged photographs, and their conversations occasionally turned intimate. "It wasn't raunchy, but it was flirtatious — and sexual at times," Akbari said.

Schuman, who said he split his time between Washington, DC, New York, and Ireland, talked about his stressful job in the financial industry.

The pair never spoke on the phone — Schuman had an Irish cellphone that was too expensive to call — and decided not to video chat.

"FaceTime didn't exist at the time, and Skype was grainy and weird," Akbari, a sociologist, told BI.

They arranged two dates in New York City, but heavy snowstorms thwarted them. "He couldn't drive from DC to see me," Akbari said. Another time, Schuman canceled because he said he was sent on a business trip to Japan at the last minute.

Meanwhile, important family occasions would happen out of the blue. "It was frustrating, but his excuses seemed plausible," she said.

The catfisher said he had cancer

Then, around two weeks after they met, Schuman said he'd been diagnosed with esophageal cancer.

"I had lost my grandfather to cancer about a month prior, and Ethan knew how close we'd been," Akbari said. "Of course, once I learned that he was sick, I wasn't going to abandon him." Adding how she felt devastated for him.

But Schuman fobbed her off when she asked to visit him during his treatment. He manipulated her by saying she was coming on too strong. Then he'd be remorseful and needy.

"I was hooked. Ethan felt more like a drug than a boyfriend," Akbari wrote in her book.

Then, after being strung along for almost a month, she contacted a friend in his mid-30s who was educated at the prestigious high school Schuman claimed to have attended. They also appeared to have overlapped at Columbia University.

"They were big schools, but my friend was very social and heavily networked," Akbari told BI. "I said I was excited because I'd met someone he might know."

She sent Schuman's photo, but the friend didn't recognize him. He asked his cohorts, checked yearbooks, and came up blank. "That's when I started to feel something odd here," Akbari said, who still gave Schuman the benefit of the doubt.

But she finally lost patience a few days before Valentine's Day 2011. Schuman backed out of plans to spend the weekend at a friend's home as part of a house swap.

She found more women who had been catfished

Soon afterward, a stranger, Gina Dallago, contacted her friend from Columbia through Facebook. She'd also been involved with Schuman and searched online for other people who attended his supposed schools in overlapping years.

Dallago sent the friend a photo of Schuman. The friend connected the two women since the man in the photo appeared to be the same man in the virtual relationship with Akbari.

They compared notes and discovered that Schuman had fed them an assortment of lies, including the cancer diagnosis and stories about serious car accidents that hadn't happened. They discussed his mentioning an on-off, long-distance relationship with a woman named Anna from the UK. The pair pieced together enough of the jigsaw to find Anna on Facebook. Akbari has honored her wishes not to disclose her last name.

Schuman had managed to con Anna for two and a half years. He'd sent her a forged driving license, power points from his supposed job, and even copies of papers he claimed to have written at MIT.

The women wondered how many other victims there were

Worse, they shared their experience of Schuman's mind games — the way he'd played hot and cold, toxically manipulating them into revealing their emotions and secrets. His other favorite tactic was to make them jealous of other women he claimed were in his life.

"We didn't know who this person was or why they were doing it," Akbari told BI. "We thought, 'How many people are out there like us?'"

Dallago confronted Schuman online. The women discovered they'd been catfished after he admitted adopting the fake name for the sake of "caution." It later transpired that he'd sent them photos of a high school friend, not him.

Akbari wrote in "There Is No Ethan," "This was not one silly fake email he'd sent. This was months and hundreds of hours spent forging a real, intimate connection while presenting us with dramatic events and life-threatening illnesses, interspersed with very real verbal and emotional abuse — all based on lies."

Still, of all the revelations, the most shocking was that Schuman was a woman. Anna recalled Schuman once telling her about his "chill" cousin and former roommate, Emily Slutsky.

They checked out Slutsky on LinkedIn — even her Goodreads profile. Her interests and biographical details — including her studies at Columbia and MIT — mirrored Schuman's.

Dallago called Slutsky's parents after finding their number on Spokeo. She posed as a friend who'd lost touch with his daughter. The dad said she was at medical school in Cork, Ireland, and gave her Slutsky's email and cell.

The women sent a message to Slutsky's email. "Received," she simply wrote back. Next, she reverted to communicating on Schuman's email. "Emily was Ethan, and Ethan was Emily," Akbari wrote in the book.

Akbari believed the mind games were about power

Slutsky, now employed as an OB/GYN at a leading teaching hospital, spoke with Dallago and Anna on the phone. She came clean but didn't explain her actions or motives. Later, she claimed she imagined the trio as characters in a novel "in her head." Akbari and the others were not convinced.

"I believe it had to do with power," Akbari said. "We know it wasn't for financial gain, but I can't speak to whether any sexual gratification was derived from this.

As for Akbari's current trust in others, she said she hadn't given Slutsky the satisfaction of ruining her relationships. "I refuse to give away that power," she said. "The exploitation of one person is not going to scare me into not living a full life."

BI contacted Slutsky for comment but has not yet received a reply. In the afterword of "There Is No Ethan," Akbari wrote that, as the book was going to print, Slutsky's lawyer sent a letter stating that "the events were in the past" and that publication of the book "would carry a very human cost."

Read the original article on Business Insider

Yahoo News

Yahoo News