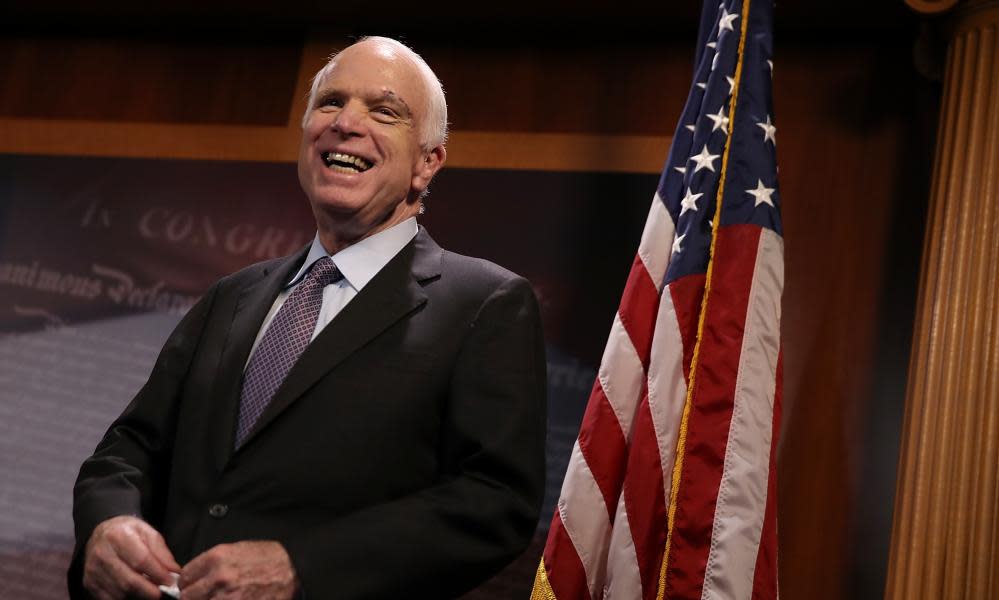

'Wait for the show': How John McCain torpedoed the Republican health plan

Minutes after the clock struck midnight, John McCain, the senior senator from Arizona, strode into the basement of the US Capitol. He was on his way to the Senate floor to cast a critical vote, as the Republican effort to repeal Barack Obama’s Affordable Care Act hung in the balance.

“Have you decided how you’ll vote?” a reporter asked McCain, as a crush of journalists surrounded the senator.

“Yes,” he said.

“How?” they responded. McCain, the 2008 Republican presidential nominee who has earned a reputation as a political maverick willing to break with his party, was recently diagnosed with brain cancer but delayed treatment to return to Washington for the debate over repealing the healthcare law.

“Wait for the show,” he replied.

Nearly two hours later, McCain delivered a dramatic thumbs-down on the floor of the Senate. Republican majority leader Mitch McConnell remained unmoved, his arms folded across his chest, as he watched McCain, the scar above his left eye still fresh from surgery, extinguish their party’s seven-year dream to repeal the Affordable Care Act – at least for now.

The moment drew audible gasps from the floor and gallery, where reporters and onlookers leaned over the balcony in suspense. Two Republican senators, Lisa Murkowski of Alaska, and Susan Collins of Maine, had already voted against the bill, a scaled-down plan to repeal aspects of Obama’s signature domestic legislative achievement that was the most the Senate GOP leadership could hope to pass. McCain’s vote was decisive.

Tension inside the US capitol built as the hours wound down. Republican leaders needed support from 50 of the 52 senators in the conference to pass the healthcare plan, a skeletal repeal plan unveiled only two hours in advance that was intended to act as a placeholder to allow further negotiations with the House.

Two no votes were expected. Murkowski and Collins had been consistent critics of the hurried and secretive process that had led to the so-called “skinny repeal” and opposed a procedural vote to open debate earlier in the week.

Throughout the evening, Republican senators derided the plan, though none as colorfully as Lindsay Graham, who called it a “fraud”, a “disaster” and a “pig in a poke”. Graham was part of a quartet of conservative senators whose prerequisite for a yes vote was an assurance from the House that the repeal plan – which at that point had not been finalized – would not be passed into law.

The House speaker, Paul Ryan, eventually committed to entering into a conference committee, where the plan could be rewritten by members of both chambers. Still, some senators conceded it was a gamble.

In the days prior, McCain surprised his colleagues with an announcement that he would return to Washington in time to help his colleagues pass a procedural motion to open debate on healthcare reform. But after that vote, seen as test of support for a later vote on repeal, McCain offered an unsparing critique of the state of the Senate, which he lamented had become “more partisan, more tribal more of the time than any other time I remember.” He also had a warning for his own party about their disregard for Senate protocol in the effort to repeal the healthcare law.

“We’ve tried to do this by coming up with a proposal behind closed doors in consultation with the administration, then springing it on skeptical members, trying to convince them it’s better than nothing, asking us to swallow our doubts and force it past a unified opposition,” McCain said in an emotional appeal on the Senate floor. “I don’t think that is going to work in the end. And it probably shouldn’t.”

In the days that followed, the Senate rejected a plan to replace the Affordable Care Act and a measure to repeal it entirely. It was unclear what compromise lawmakers could reach in conference that could win enough support in the Senate. The bill Republicans settled on, their last hope for passing healthcare legislation before the summer recess, would have removed the individual mandate – a key aspect of Obamacare which requires all Americans to have health insurance or pay a fine – and made other changes to the Affordable Care Act’s structure.

Still, the watered-down “skinny repeal” would increase the number of people who are uninsured by 15 million next year compared with current law, the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office estimated. It would also raise premiums by 20%, the budget office said.

At around 11.30pm, vice-president Mike Pence’s motorcade swept into the Capitol. As president of the Senate, his vote would be needed in the event of a tie. His arrival set of speculation that perhaps Republican leaders had wrangled 50 votes to pass the bill.

“Here we go,” McCain said playfully as he stepped on to the Senate floor.

In the chamber, McCain sat next to Graham, his closest friend in the Senate. John Cornyn, the No 2 Senate Republican and majority whip, gave a thumbs-down, which was interpreted ominously by observers. Then Pence walked over, and he and McCain engaged in a protracted and animated discussion.

Though no votes had yet been cast, the delay and the body language between them suggested that the White House had failed to persuade McCain, the senator Donald Trump had hailed as an “American hero” for returning to Washington to vote on healthcare – a complete reversal from Trump’s vicious attacks on McCain, a former prisoner of war, during the election campaign.

McCain placed his hand affectionately on the vice-president’s arm and shook his head.

The discussion continued until Pence eventually walked off the floor. When he returned, an aide informed McCain that he had a call. CNN reported it was Trump on the line.

After the call, McCain returned to the floor and crossed over to the Democratic side to speak to Chuck Schumer, the Senate minority leader. At least 20 Democrats joined the huddle, unable to mask their smiles. McCain, a senator later recounted, told the group he was worried that the reporters watching from the gallery would read his lips. Senator Dianne Feinstein hugged him.

Then, so did Orrin Hatch, a Utah Republican.

“I don’t know why he does what he does,” Hatch told reporters after the vote. “But he’s still a hero of mine.”

Voting began a few minutes before 1.30am. Murkowski and Collins had already cast their votes by the time McCain returned to the floor, approached the bench and raised his arm. He tilted his thumb down, said a clear “no”.

“Certainly Senator McCain knows how to improve the drama,” Senator Bill Cassidy, a Republican from Louisiana, said after the vote.

Asked later if he could remember a more dramatic night than that, Schumer shook his head. Then he turned around and corrected himself: “The birth of my daughter.”

The final tally was announced, and the plan had narrowly failed, 49 votes to 51. It was a humiliating setback for McConnell, a supposed master tactician who had spent the last three months writing and rewriting drafts of legislation that could earn the bare minimum number of votes and cajoling his members to support it. But he had refused to open the process to public debate – and insisted on a vote before the legislation was finalized.

McConnell’s voice swelled with emotion as he conceded defeat in a speech from the Senate floor.

“This is a disappointment, a disappointment indeed,” the majority leader said. “I regret that our efforts were simply not enough this time.”

For seven years, Republicans have promised voters that they would repeal the Affordable Care Act, Barack Obama’s signature legislative achievement that extended health coverage to more than 20 million people. Before Trump took office, Republicans – who vociferously opposed it as unwarranted government intrusion – voted dozens of times to repeal the law, and in 2015 succeeded in sending a bill to Obama’s desk, which he vetoed.

Now, Trump sat, “pen in hand”, ready to sign just about any healthcare bill that came his way.

Though he earned raucous applause as a candidate for promising to repeal the law, Trump also assured voters he would not scale back Medicaid and Medicare, the insurance programs that help cover low-income and older Americans. Before his inauguration, Trump promised his healthcare replacement plan would provide “healthcare for all”. The plans put forward by the House and Senate, however – which Trump seemed eager to sign – did anything but.

Over the past seven months of furious negotiations in the House and Senate, Republicans struggled to overcome deep ideological and demographic divisions about how to move forward.

In May, after a series of fits and starts, the House passed a bill that would eliminate the law’s individual mandate. It would also roll back the state expansion of Medicaid. Trump celebrated with Republicans in the White House rose garden.

The Senate rejected the House plan, but quickly ran into obstacles as they began drafting their own. Moderates – such as Collins and Murkowski – were concerned about cuts to Medicaid, while conservatives who championed small government were not satisfied with any plan that fell short of a wholesale repeal. McConnell established a working group – originally comprised of 13 Republican men – and eventually set about writing the Senate bill himself.

Despite pleas from Democrats and members of his own party, McConnell kept the bill under wraps for most of the negotiating period, and refused to hold a public hearing on the legislation.

The options that emerged in the final days were a straight repeal of the law, with a delayed implementation period that would give Republicans two more years to find a replacement; and a replacement plan that would have repealed key provisions of the law and rolled back Medicaid. Analyses by the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office found that, if enacted, between 22 million and 30 million people would lose coverage over the next decade.

Meanwhile, opinion polls showed growing support for the Affordable Care Act, compared with dismal approval ratings for the replacement plan.

Neither the straight repeal nor the replacement plan appeared to have the votes to pass – and McConnell was ready to move on. But in a last-ditch effort, the president intervened, and encouraged Republicans to return to the table. Trump had been largely hands-off during negotiations, tweeting sporadically and inconsistently about what he wanted from the Senate.

At one point, he endorsed a strategy to repeal the law without a replacement, which would create chaos in the insurance markets and, he calculated, force Democrats to the table. Then he demanded Republicans deliver a replacement plan as well. In a lunch with Republican senators before the vote, he threatened that the lawmakers who were his friends “might not be very much longer” if they voted against the bill.

Perhaps most insightful was his comment that under Obama, Republicans had an “easy route: we’ll repeal and replace and he’s never going to sign it”. But, he added: “I’m signing it.”

The vote’s failure represented a humiliating defeat for Republicans. It was also an embarrassing setback for an unpopular president, who, mired in controversy and stymied by opposition, has yet to chalk up a major legislative achievement.

As they consider their next steps, Republicans must also acknowledge the growing American consensus that the government has a responsibility to guarantee healthcare. A Pew survey found that 60% of Americans believe the federal government should be responsible for ensuring healthcare coverage, compared with 38% who say it should not. The share of people with this view grew from 51% last year and now stands at its highest point in nearly a decade, according to Pew.

Leaving the floor in the early hours of Friday morning, Republicans looked stunned and despondent after the theater of the past few hours, a denouement to a dramatic several months. Some conservatives vowed to continue fighting for repeal, while others suggested a bipartisan route was the only way forward.

“Mark my words, this journey is not yet done,” said Senator Ted Cruz, a conservative from Texas, who wants the healthcare law eliminated entirely.

Trump himself suggested sabotaging the ACA and forcing Democrats to the table. “As I said from the beginning, let Obamacare implode, then deal. Watch!” he tweeted.

But Murkowski, who disappointed her colleagues with a decision she described as “very difficult”, said she hoped the vote would lead to an “open and full committee process, bipartisan participation and then hopefully we’ll be able to build something”.

McCain, who would still like to see the law reformed, endorsed that view. “The vote last night presents the Senate with an opportunity to start fresh,” he said in a statement. “It is now time to return to regular order with input from all of our members – Republicans and Democrats – and bring a bill to the floor of the Senate for amendment and debate.”

He added: “I encourage my colleagues on both sides of the aisle to trust each other, stop the political gamesmanship, and put the healthcare needs of the American people first. We can do this.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News