Should charities accept contrition cash from dubious donors? Beth Breeze

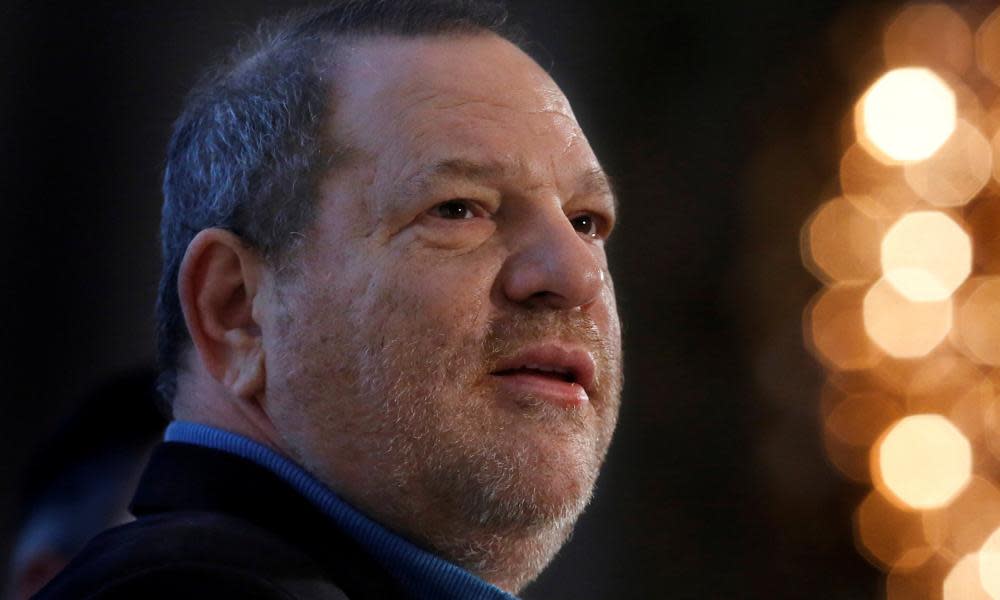

Hollywood mogul Harvey Weinstein faces multiple claims of sexual harassment and now also stands accused in the court of public opinion of trying to redeem his reputation through charitable donations. His offer of a $5m fund to support female film-makers was rejected after widespread criticism of this seemingly calculated “contrition cash”, including a petition calling on the University of Southern California to reject his gift.

The textbook example is the refusal of tobacco money by cancer charities

How to respond to such offers is a longstanding challenge for charities. When William Booth, who founded the Salvation Army in 1865, was asked about the ethics of accepting charitable donations from questionable sources he is supposed to have replied: “The trouble with tainted money is t’aint enough of it.”

That nonchalant response reflects the perennial need for more income to fund good works and, perhaps, a lack of concern about consequences. Today’s charity leaders need a more nuanced position to avoid getting on the wrong side of the powers that be or, arguably worse, of public opinion.

Official guidance on the acceptance or refusal of donations is clear-cut in principle: the Charity Commission compels trustees to act in the “best interests” of their charity and guidance from the UK Institute of Fundraising encourages all charities to have a policy in place that sets out what this means in practice. The textbook example is the refusal of tobacco money by cancer charities.

Unfortunately, such scenarios are rarely so straightforward, and the challenges for charities faced with potentially dubious donors involve both pragmatic and ethical decisions.

The pragmatic challenge is essentially a cost-benefit analysis: does the promised cash outweigh any potential drop in income if a backlash occurs? The “price of acceptance” goes beyond the impact on existing and future donors who might fear taint by association. It also includes the cost of offending beneficiaries and demoralising employees who believed they were working for a different sort of organisation.

These latter factors segue into the ethical challenge: charities are meant to be values-based, and need to operate with especially high levels of integrity to maintain that. Even if a charity is experiencing a severe funding crisis, accepting a gift that risks actual or apparent conflict with its core values could cause long-term harm to the charity’s reputation and raison d’etre.

The public might be surprised to hear how much these questions vex fundraisers and the polarised opinions that exist in the sector. Some dispute the notion that money can be “infected” by its owner’s deeds, while others will refrain from applying to charitable trusts and foundations if there are any concerns about the character of its historic founder.

Of those who do accept contentious donations, some take Booth’s “greater good” position, believing it is more important to keep their doors open and serve beneficiaries. Others, especially, in my experience, those working in charities with religious roots or ethos, embrace the idea that a donation can offer redemption for the donor, asking that they should not stand in the way of a repentant sinner.

There are those charities that err on the side of caution. That might, for instance, include the Shropshire hospital that refused a donation raised by men dressed as female nurses and the Scottish homelessness charity that declined a donation raised from selling a calendar featuring images of clothed pole dancers. In both cases, I would suggest more pragmatic fundraisers would have taken the cash. Overall, the most common view I’ve encountered is a willingness to set aside personal judgments of any given donor where there is no direct conflict with the charity’s objectives.

Fundraisers are also keenly aware that the role of donation door-keeping involves a large dose of guesswork, because the true costs of accepting tainted donations are unknowable. The potential for a bad news story to blow up is not always realised; who now recalls which charities did and did not accept donations from the final edition of the News of the World in 2011? And did those who rejected it – including the RSPCA and the Salvation Army – wish they had followed the Disasters Emergency Committee’s example in clarifying that they did not condone the “unconscionable behaviour” of some News of the World journalists and executives, but were rather following a humanitarian imperative to raise the maximum income to help their beneficiaries?

We will never know whether Weinstein’s spurned $5m donation could have had a positive impact on gender equity in the film industry, or whether acceptance of that gift would have undermined advances made by the exposure of long-term, systemic sexual harassment in Hollywood and beyond. With no hard data to model the relative pros and cons of “contrition cash”, these are not easy calls to make.

Beth Breeze is the director of the Centre for Philanthropy at the University of Kent. Her book, The new fundraisers: who organizes charitable giving in contemporary society? describes the identity, motivation and everyday working practices of successful fundraisers.

Talk to us on Twitter via @Gdnvoluntary and join our community for your free fortnightly Guardian Voluntary Sector newsletter, with analysis and opinion sent direct to you on the first Thursday of the month.

Looking for a role in the not-for-profit sector, or need to recruit staff? Take a look at Guardian Jobs.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News