Democrats are being swept up in idealism – but are they ignoring political realism?

The Democratic National Convention that will take place in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, this July is almost certain to make history. The party may choose the first openly gay presidential candidate ever, or the first Jewish candidate, or the first democratic socialist candidate from either of the two major parties. The convention could choose the oldest presidential nominee in US history, or the second youngest, or the richest. It may select the second woman ever to head the ballot.

But the Milwaukee gathering may also turn into the first brokered convention since 1952 – a dream come true for political junkies who would revel in the Game of Thrones level of intrigue it would entail, but a nightmare for party strategists. And the convention may be most remembered for choosing the candidate who ended up losing to Donald Trump – an outcome that seems likelier after last week’s Democratic debate in Las Vegas, Nevada.

Related: Bernie Sanders is cruising towards the Democratic nomination. But can he win? | Richard Wolffe

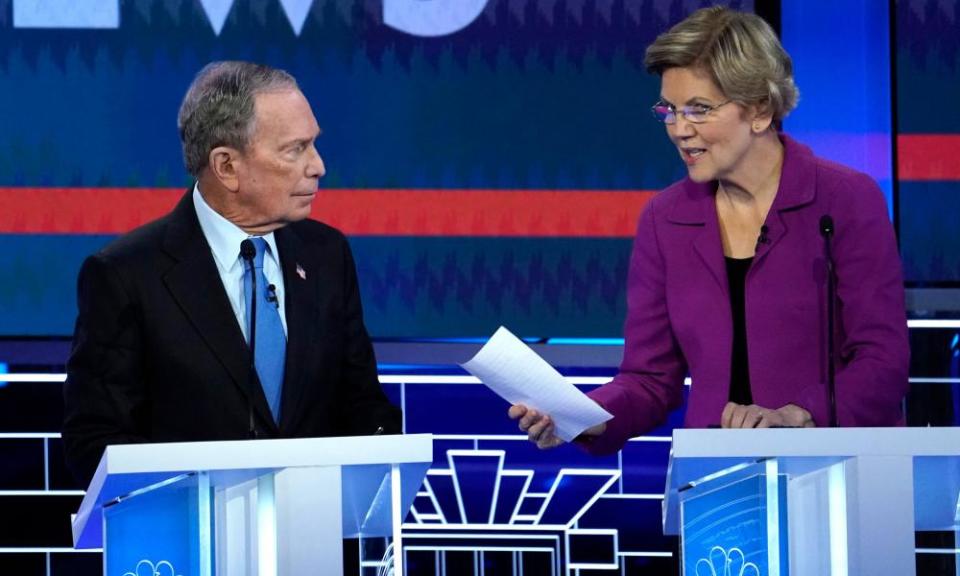

That event marked the disastrous debate premiere of the former New York City mayor Mike Bloomberg, whom the other candidates hammered like a piñata. But all of the candidates also attacked each other more vigorously than they had in any previous debate. In so doing, they laid bare the divisions within the Democratic party that are likely to lead to grief both at the convention and on election day.

Many Democratic moderates, alarmed by Bernie Sanders’ standing atop national polls, look to Bloomberg to thwart a socialist party takeover. In his ads, at any rate, Bloomberg comes across as a formidable candidate: a hugely successful entrepreneur, generous supporter of progressive causes, three-time electoral winner in a vast and diverse city and a manager of proven competence and toughness. Since Democratic voters say their top priority for a candidate is electability, it might appear logical to select a moderate nominee who’s an experienced national figure, who can torch Trump’s claims of business success, who can credibly promise an orderly and competent administration to replace Trump’s chaos and who can’t be intimidated or outspent.

But the other candidates in Las Vegas highlighted Bloomberg’s egregious vulnerabilities. These include claims of sexual harassment and gender discrimination at his company that led to an unknown number of women filing lawsuits resulting in settlements and non-disclosure agreements (or NDAs), as well as anger over the stop-and-frisk policies of New York’s police force during his mayoralty that targeted young black and Hispanic men. More generally, the other candidates charged that Bloomberg is an “arrogant billionaire” (according to Elizabeth Warren) “who thinks he can buy this election” (according to Pete Buttigieg).

Bloomberg had no real reply to these charges. He is, in fact, one of those billionaires whom Sanders and other progressive Democrats have effectively demonized, and he’s pouring Babylonian sums into his candidacy. Arrogance may be the flaw that politicians ascribe to other politicians who are just as egocentric as they are, but the debate clearly showed that Bloomberg isn’t accustomed to being challenged and apparently can’t be bothered to take advice from his debate prep coaches.

At age 78, Bloomberg is a product of the pre-#MeToo era and hasn’t learned how tone-deaf it sounds when he says that he won’t release women from NDAs because the contracts were “consensual”. And his signature achievement of reducing crime in New York City has become a liability because it was achieved in part through stop-and-frisk. Bloomberg might be tempted to point out (as he has in the past) that minorities, who are disproportionately victims of violent crime, were the greatest beneficiaries of his crime reduction efforts. But even conservatives who once advocated stop-and-frisk have conceded that crime rates have continued to fall in New York since the practice was discontinued, and further that since the vast majority of those who were stopped and searched were innocent of any crime, the practice unnecessarily and unjustly humiliated those who were subjected to it.

Despite Bloomberg’s epic debate fail, he’s no likelier to drop out of the race than he is to run out of money. Already he has spent 10 times as much as his rivals in the 14 states that will hold primaries on Super Tuesday (3 March). He won’t win anything close to a majority of primary votes, but the power of advertising means that he’s likely to come away with something like 15%. This will make it all but impossible for other moderate candidates, like the fading Joe Biden and cash-strapped Amy Klobuchar and Buttigieg, to break out from the pack. And it’s difficult to picture any of the moderates uniting behind any one candidate, given the animosity they showed toward each other in Las Vegas. (Buttigieg spent much of the debate needling Klobuchar, while Klobuchar glared at Buttigieg as if he were an uppity intern who needed a stapler thrown in his direction.)

Sanders is the only candidate who’s making that kind of breakout, and he’s the only candidate besides Bloomberg who’s sure to have enough funds to sustain his candidacy through the convention. But if Warren enjoys a resurgence as a result of her slashing debate performance, that will cut into Sanders’ margins. And his far-left policies, while they energize his young base, are likely to repel larger numbers of voters in most states. A Gallup poll that came out this month found that 53% of all Americans would not vote for a socialist, while majorities of Democrats oppose Sanders’ “Medicare for All” plan when pollsters specify that it would mean the end of private health insurance.

So it’s increasingly possible that Sanders could come to the Democratic convention with a plurality but not a majority of delegates. Sanders was the only candidate at the Las Vegas debate who insisted that “a candidate with the most votes should become the nominee”, while all the others maintained the official rules requiring a nominee to win an outright majority should be upheld.

What would happen in that situation? It doesn’t require a crystal ball to foresee that Sanders would cry that “the will of the people” was being thwarted by malign party elites, just as many of his supporters cling to the false claim that Hillary Clinton and the superdelegates cheated Sanders out of the 2020 nomination. Sanders, who has spent virtually all of his political career as an independent aside from those periods when he has run for president, has no institutional loyalty to the Democratic party. And only a little more than half of his supporters say they will definitely support the eventual Democratic nominee if it isn’t Sanders.

My guess is that under those circumstances, the party establishment would yield to a Sanders nomination rather than risk a mass defection of his supporters. But there would be hard feelings among the comparative moderates, particularly if – as was the case in the Iowa caucuses and New Hampshire primary – candidates other than Sanders and Warren received a majority of the primary votes.

So the likelihood is that a badly divided Democratic party will emerge from its convention with Sanders as the nominee. And then, for reasons that I have previously described, a united Republican party will go into full gear to portray Sanders as a treasonous, anti-American communist. That propaganda campaign will be brutal and unfair – and highly effective. Already Republican congressional candidates, particularly in the purple states and the suburban districts that swung Democratic in 2018, are salivating at the prospect of tying their opponents to Sanders’ Soviet-style socialism.

In vain will Sanders’ youthful supporters protest that his “democratic socialism” means something entirely different from plain old socialism, let alone communism. Presidential campaigns do not lend themselves to fine distinctions of that sort, and if Democrats are forced to spend all of their time on defense they will lose on an epic scale. I truly hope this isn’t the outcome. But I fear that 2020 will teach the Democrats a costly lesson about the dangers of getting swept up in ideological movements distinguished more by enthusiasm than political realism – which histories sometimes refer to as “children’s crusades”.

Geoffrey Kabaservice is the director of political studies at the Niskanen Center in Washington DC as well as the author of Rule and Ruin: The Downfall of Moderation and the Destruction of the Republican Party

Yahoo News

Yahoo News