The deranged Planet of the Apes sequels Charlton Heston tried to kill

Charlton Heston did not want to return to the Planet of the Apes. The original film, released in 1968, had been an unexpected, extraordinary smash hit. But in those days, as Heston later said, making a sequel “was considered faintly tacky”. Twentieth Century Fox, however, was on the verge of bankruptcy. The studio needed a hit. It needed another Apes picture: Beneath the Planet of the Apes, which landed in cinemas in June 1970.

Heston was persuaded to return – guilted into it by a desperate studio boss – but only on the condition that Heston’s character was killed. Heston didn’t stop there. He wanted to kill off the entire planet with an atomic bomb. Damn them all to hell indeed.

But even the annihilation of Earth couldn’t stop them from going, well, ape for more sequels. Indeed, Beneath the Planet of the Apes was one of the first of its kind – a primitive blockbuster sequel – that began an evolution of sequel-making.

The series, produced by Arthur P Jacobs, churned out four cash-in sequels in as many years – all interesting though sometimest bizarre – and became an inadvertent blueprint for movie franchises: sequels, TV spin-offs, and merchandise. And while navigating the same problems that would face many future sequels: stars not wanting to return, dwindling budgets, and writing out of creative corners.

“I saw the first Planet of the Apes when I was eight years old,” says Edward Gross, co-author on a new two-book series, The Unofficial Oral History of Planet of the Apes. “In those days you didn’t know a new one was coming out until you saw the trailer or the poster. There was no internet, no publications talking about it. Suddenly you’re in a movie theatre and see a trailer for Conquest of the Planet of the Apes. Oh my god!”

As the franchise’s latest evolutionary specimen, Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes, swings into cinemas, the 1970s sequels remain as big an influence as the original film. At the time of Beneath the Planet of the Apes, however, the original film – particularly the Statue of Liberty twist ending (it was Earth all along!) – cast a big shadow.

As described in Planet of the Apes Revisited – by Larry Landsman, Joe Russo, and Edward Gross – various ideas were discussed. Pierre Boulle, author of the original novel – La Planète des Singes – wrote a version called Planet of the Men, in which Dr Zaius would devolve into a regular old orangutan. The Twilight Zone creator Rod Serling – who wrote the first film and came up with the Statue of Liberty twist – offered an idea about Heston’s character trying to bring back mankind.

Serling was unavailable, however, so British writer Paul Dehn – screenwriter for Goldfinger – was hired. He suggested that the sequel should start with the end of the original movie. What was beneath the Statue of Liberty? The ruins of New York and the survivors of the nuclear war that wiped out most of mankind, as it turns out. (Which makes sense. It’s always seemed a tad daft – even in a film about talking chimps – that all that remains of New York in the original film is half a statue.)

Meanwhile, associate producer Mort Abrahams was fixated with creating a visual shock to rival the Statue of Liberty reveal. The result was the creation of a third species on the planet – human-looking mutants who descended from the survivors of a nuclear war 2,000 years earlier. They live in the subterranean ruins of New York and worship an unexploded Alpha-Omega atomic missile. The shock moment comes when they whip off their human masks and reveal their true appearance: hideous, veiny ham-like faces.

“Mort Abrahams came up with the mutants,” says Gross. “A lot of people tried to dissuade him from that idea, but it just didn’t work. He insisted!” Another idea, about a half-human half-ape child – which got as far as makeup tests – was abandoned over the implication of bestiality.

The man at the top – Fox’s head of production, Richard Zanuck – was more concerned with one man than he was mutants or apes: Charlton Heston. As detailed by Aubrey Solomon in his book, Twentieth Century Fox: A Corporate and Financial History, the studio had losses of $77.7 million in 1970. This studio had taken hits from big budget money-losers that included Dr Doolittle, Hello Dolly, and the Julie Andrews musical, Star! Twentieth Century Fox was not alone. Other studios were suffering in 1970. According to Solomon, just one in the eight films made back their cost. Fox’s woes eventually led Zanuck’s father, Darryl Zanuck – the studio boss – to oust his own son in a humiliating public power struggle.

In the meantime, Richard Zanuck talked Heston into returning as Taylor, the stranded astronaut from the first Apes film. Sequels at this time were sneered at – certainly not the stuff of Charlton Heston-starring studio pictures – but Zanuck reminded Heston that he’d taken a chance on the original, which was a financial risk and, on paper, quite ridiculous. Now he needed a favour from Heston. “If Charlton Heson signed for Planet of the Apes today, he’d sign for six movies,” says Gross.

It was agreed that Heston would appear at the start of the film and then return at the end to be killed off. Taking Heston’s place as leading man was James Franciscus (who is, to be fair, quite Heston-like). Maurice Evans returned as stuffy statesman orangutan Dr Zaius. But others were reluctant. Kim Hunter, who played chimp doctor, Zira, said, “I did not want to go back and do that ever again as long as I lived,” though she ultimately did return. Roddy McDowell, who emerged as the series’ true star as both Cornelius and Caesar, was unavailable – replaced for Beneath by David Watson – while director Franklin J Schaffner went off to make Patton. Ted Post, director of Hang ‘Em High, took the helm instead.

Nobody was happy with the script, including Ted Post and James Francisisus, who had a bash at rewriting it himself. Post had other frustrations. The budget was cut in half – from $5 million to $2.5 million. “They lowered the budget for each one,” explains Gross. “Now they’d pump in more money for a sequel – bigger is better! Though it doesn’t always work that way. Back then the formula was: your sequel will only make so much of what the original did, so the budget gets adjusted, so the budget for each sequel goes down.”

Heston was also unhappy during production. As noted in Planet of the Apes Revisited, he described the sequel in his journal as “my promised chore” and admitted “I’m beginning to regret it.” It was the first film “I’ve ever done in my life for which I have no enthusiasm”.

Beneath the Planet of the Apes is more strange than bad – somewhere between out-there, esoteric science-fiction and just scrambling around for any old nonsense. There’s some good gorilla-on-horseback-chasing-humans action – exactly what you want from Planet of the Apes – with disturbingly stark visuals: the apocalyptic ashes of New York and crucified apes, upside-down and burning. By the time mutants whip off their faces and sing All Things Bright and Beautiful to an atomic bomb, it’s gone utterly bonkers.

The end is bleak, which is part of the Apes tradition, as the heroes are all shot dead, and Heston’s Taylor detonates the Alpha-Omega bomb. “Name me a Planet of the Apes that doesn’t have a bleak ending,” says Gross, laughing. Heston took credit for pushing the button. “Heston always claimed it was his idea,” says Gross. “He really hated the idea of being in that movie. He felt there was nothing left to play except, as he put it, ‘adventures among the monkeys.’ It was his way of saying ‘no more sequels.’ It didn’t work that way!”

Beneath the Planet of the Apes opened in May 1970. It made $19 million, which – considering its lower budget – made it another money-spinner for Fox. Even with the world obliterated, writer Paul Dehn received a telegram that said: “Apes exist, sequel required.” The result was Escape from the Planet of the Apes, released exactly a year later.

Sequels often need to get creative and undo decisions made by previous installments. Back to the Future II had to come up with a plot in the future involving Marty McFly’s kids – because of a throwaway joke at the end of the original (“It’s your kids, Marty! Something has got to be done about your kids!”) – while Marvel has imported comics’ laziest plot device, the multiverse, to bring popular characters back from the dead.

Dehn came up with a shrewd idea: that Zira and Cornelius (played by Roddy McDowell again), plus a third chimp, Dr Milo (Sal Mineo), escape on Taylor’s spaceship just before the explosion and are blasted back to 1970s Los Angeles.

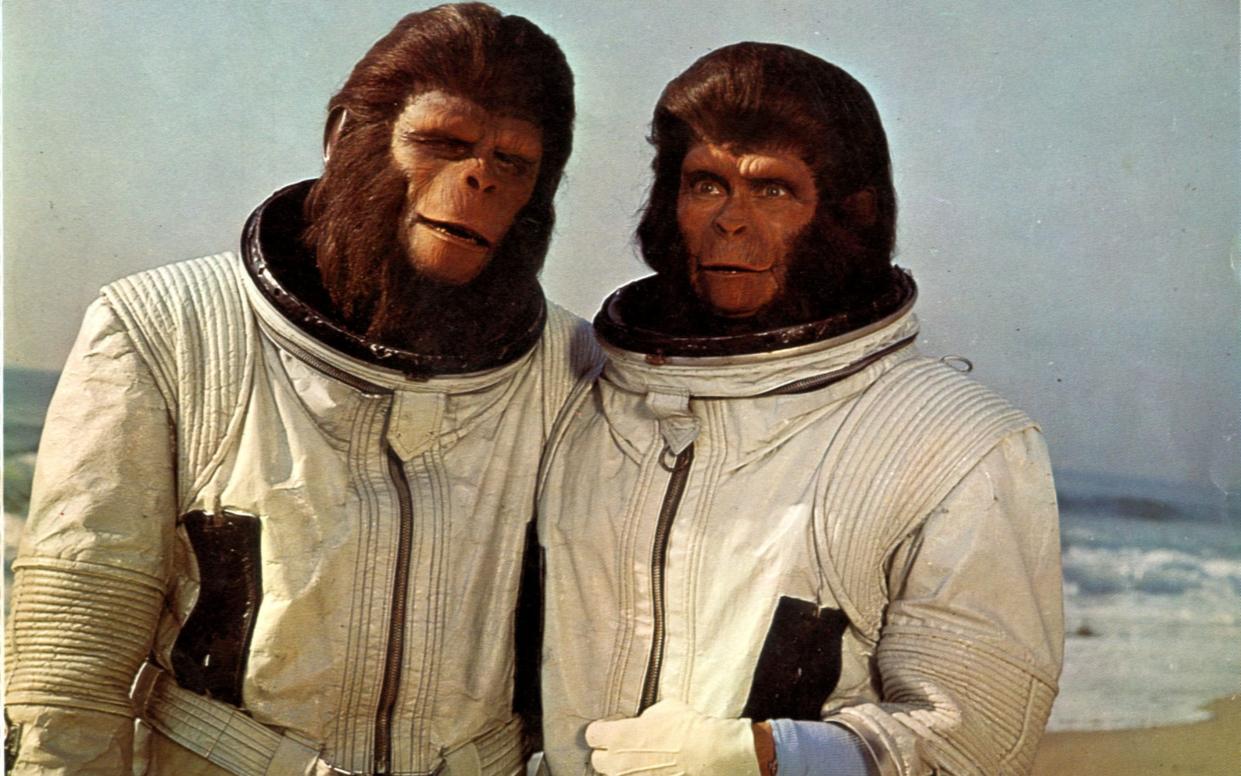

In the opening scene, the spaceship crash lands in the sea. The army rushes to meet the astronauts, who emerge from the craft and remove their helmets – revealing that they are in fact chimpanzees. Though Mort Abrahams had departed by this point – replaced as associate producer by Frank Capra Jr (son of the It’s a Wonderful Life director) – the opening scene of Escape from the Planet of the Apes is as close as the series got to recreating that the Statue of Liberty moment, punctuated by the beats of Jerry Goldsmith’s score. Director Don Taylor, who took over for Escape, recalled that viewers at the preview screening broke into applause when the ape astronauts took off their helmets.

There’s a cliché about film series going to space when they run out of ideas. The inverse can be true: science-fiction series that begin in space, or in sci-fi settings, come back to modern-day Earth (see the humpback whale-saving antics of Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home, or Red Dwarf coming up with contrivances to get back to Earth every other week).

“In this case it was a financial decision – they were driven to do something cheaper,” says Gross. “If you’re going to do a sequel after blowing the Earth up, you either go to a different planet or bring them to 1970s Los Angeles and your sets are already built. What they came up with happened to be a creative solution that worked out really well. I don’t think anyone expected Escape to be as good as it is.”

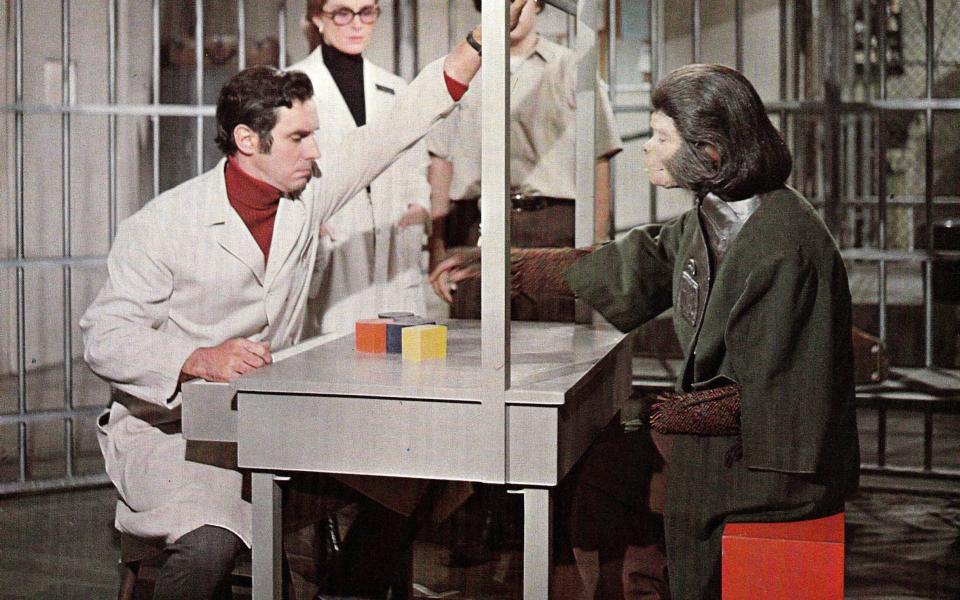

Certainly, it was cheaper, with the budget down to $2 million. Production only needed to do make-up for three chimps, plus a dodgy man-in-suit gorilla that throttles Dr Milo to death. But it’s a sharp idea, too. Cornelius and Zira are first locked up and experimented on before Zira reveals she can talk, which leads them to being put before a presidential inquiry. “Does the other one talk?” asks the examiner, pointing to Cornelius. “Only when she lets me,” says Cornelius, looking at the missus – a bit of ironic sexism that gets a rapturous applause.

In a story that feels just as prescient in the age of TikTok, the chimps become celebrities – wined and dined by high society and dressed up in fancy clothes. It’s the closest the films come to Pierre Boulle’s original book – in which a human astronaut is paraded about a contemporary ape society like a novelty talking pet – but with the roles reversed.

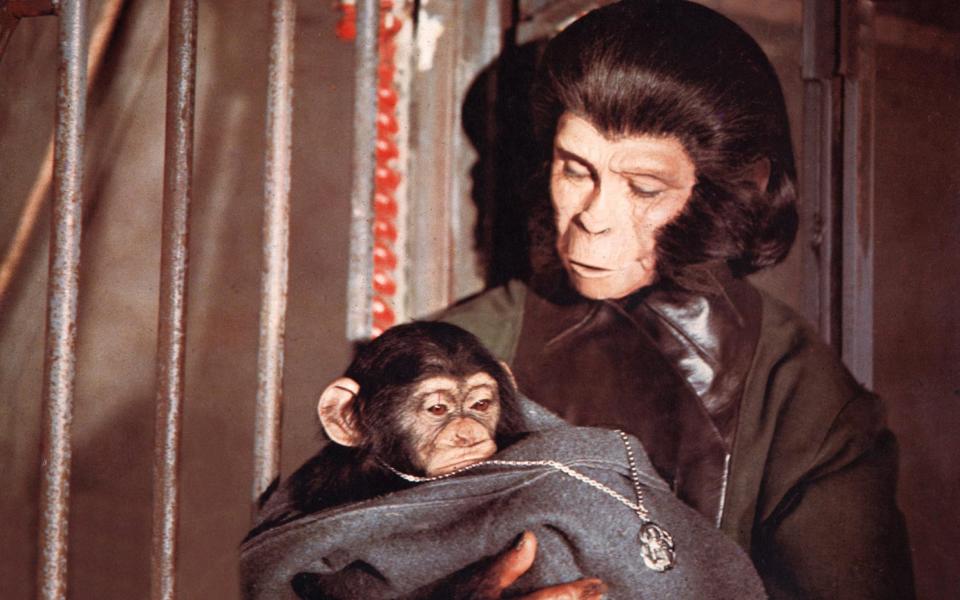

When the humans learn that apes will one day dominate the planet – and that Zira is in fact pregnant with a chimp that could overthrow mankind – the apes become a threat. “Escape starts off this lovely light comedy about these apes turned into celebrities,” says Gross. “It takes this dark turn when they’re hunted and slaughtered ultimately.”

Indeed, the ending is sinister stuff: Cornelius and Zira – and their newborn baby – are gunned down. Incredibly, it outdoes the end of the previous film – it manages to out-bleak the actual end of the world. Though we learn that their baby was switched with a circus chimp. The smart baby chimp lives.

Escape from the Planet of the Apes was another success – Roddy McDowell’s favourite and the critical high point of the Apes sequels. There was a feeling that it could have made more money, however. It was poorly supported by Fox marketing, and Don Taylor thought it was hurt by the disappointing weirdness of Beneath the Planet of the Apes.

Escape has a curious place in the series – a sequel, a prequel, and an origin story. Cornelius at one point explains the Apes backstory. A virus killed domestic killed cats and dogs, so humans took in apes as domestic pets. But humans treated the apes like slaves, so the apes rebelled after the first ape told the humans, “No”. In the next film, Cornelius and Zira’s son, Caesar, leads the rebellion that founded the ape society. The backstory is loosely recreated in the modern reboot series, which began with 2011’s Rise of the Planet of the Apes and stars a motion-captured Andy Serkis as Caesar. Other modern reboots erase previous sequels – such as the Halloween or Terminator reboots – but the recent Apes films take their lore from the sequels as much as the original.

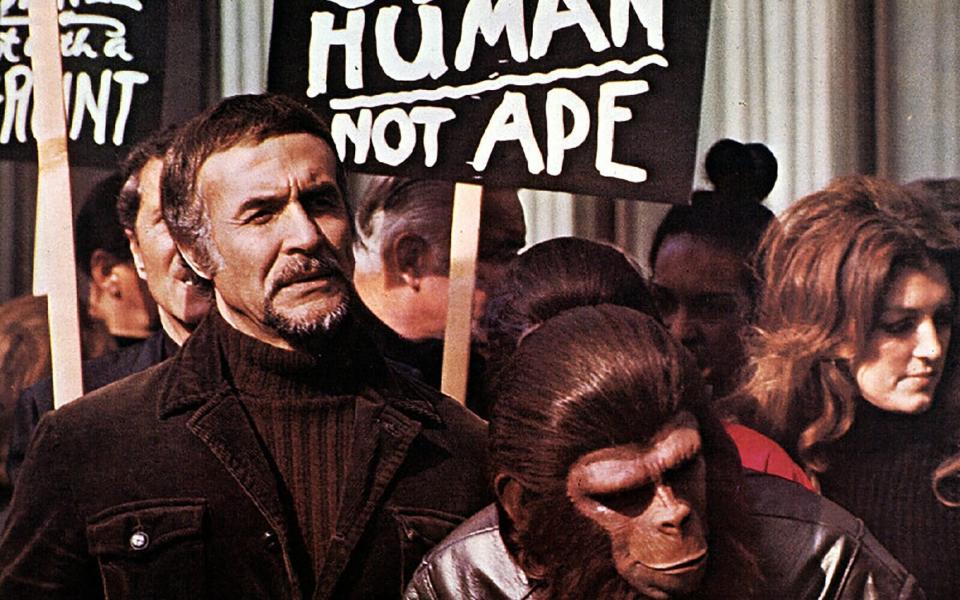

Following Escape, there was immediate talk of a fourth film. Written again by Paul Dehn and directed by J Lee Thompson (director of The Guns of Navarone), Conquest of the Planet of the Apes arrived in cinemas in June 1972. Set 20 years later, apes are enslaved by a totalitarian regime while Caesar – also played by Roddy McDowell – hides his identity and intelligence. Roped into the system of ape servitude, he leads an uprising.

There’s a dark, retro oddness to Conquest: a futuristic fascist state done 1970s style, where men in sort-of Nazi uniforms abuse apes – taunting them with bananas then blasting them with flame throwers – under vibing kaleidoscopic lights. Despite a few good eggs through the Apes films, humans are asking for their downfall at every turn. Scenes of apes being tortured are weirdly affecting – particularly Caesar being electrocuted. It’s literally darker, too. Lots of it was filmed at night to hide the ever-cheapening ape masks.

The apes go from serving drinks (badly) for their human masters and shining shoes (also badly) to gun-wielding revolution. The scenes of ape-on-human riots are still strikingly violent and emulate the 1965 Watts race riots. The rioting scenes, however, were toned down after the previews. “I remember seeing another cut,” says Gross. “When the apes are fighting back there was a lot of blood – a lot of murders of humans. People were freaking out – ‘Are we going to incite more violence?’

It’s fascinating that Planet of the Apes lends itself so well to social conscience and political allegory – from the morality play of the original to reality-based riots, via less-than-subtle recreations of Vietnam protests (“Wage peace not war,” the chimpanzee pacifists plead with the militaristic gorillas).The apes hold up a mirror to humankind – sometimes showing man at his most beastly.

At the end of Conquest, Caesar makes a searing speech, declaring that apes will take control of the planet from humans – “And that day is upon you now!” Originally, his army of gorilla rioters then battered the film’s ape-tormenting governor to death. But the scene was deemed too strong. With no time or money for reshoots, McDowell recorded some extra lines, declaring compassion for humans after all. The lines were badly dubbed over the top of the scene – a total contrast to what Caesar had said just one minute earlier.

The original end – included on the Blu-ray edition – is McDowell’s most glorious moment as Caesar. “What he does with that character is astounding,” says Gross. “He conveys so much emotion through the makeup. It blew me away. Even the badly dubbed version.” There’s a darkness in Caesar, shades of which carry over to Andy Serkis’s reboot version.

Conquest of the Planet of the Apes was another money-maker – $9.7 million from a $1.7 budget – and led to the final film of the original series, Battle for the Planet of the Apes, released in June 1973. Even before the production began, it was understood that Battle would be the end. “Everybody knew it was over,” says Gross. “I think the diminishing returns had diminished pretty much all the way – though it still made a profit.” He adds: “Conquest had a vision and a scope. I think everyone was burned out by Battle.”

On a budget of just $1.2 million, the ape makeup isn’t quite up to scratch (modern advancements in HD have not been kind to the background apes in any of the sequels). The script was passed between writers and J Lee Thompson – who returned to direct – wasn’t unhappy with the finished version. “It was the fifth film and it wasn’t very good,” he later told Gross and his co-authors. “Battle is weak,” says Gross. “Dramatically, it’s weak. It’s a kids’ movie. I guess they wanted to go in the opposite direction to Conquest, which is so dark.”

The film is set after nuclear war has destroyed civilisation. Caesar has started an ape settlement, living sort-of harmoniously with a handful of humans – though the thuggish, thick-headed gorillas are up to no good. Nuclear war survivors then turn up for a (budget conscious) war. It feels like a film destined for Sunday afternoon television, though it gives us the ape vs human smackdown – which has been on the cards for roughly 2,000 years by this point.

Caesar also breaks the most important rule of ape-kind – “ape shall never kill ape” – when he fights to the death with a gorilla named Aldo. The fight is recreated in 2014’s Dawn of the Planet of the Apes, when Andy Serkis’ Caesar battles human-hating troublemaker, Koba, played by Toby Kebbell.

A 14-episode TV series followed in 1974 and a cartoon series in 1975, Return to the Planet of the Apes. There were efforts to remake Planet of the Apes in the 1980s and 1990s, with various filmmakers attached at various stages: Adam Rifkin, Oliver Stone, Chris Colombus, James Cameron, and Arnold Schwarzenegger. The eventual Tim Burton-directed remake – or “reimagining”, as it was called – was released in 2001. Few people have got anything good to say about it. “The makeup looks great!” says Gross.

When Beneath the Planet of the Apes was released in 1970, the closest equivalent was the James Bond, though Bond has always existed on its own terms – individual adventures sold on being bigger, more outlandish, more expensive with each installment. The Apes films preceded a more common species of sequel: wringing every possible dollar from a tried-and-tested film brand. But in the case of Planet of the Apes there’s more to them than monkeying around in ropey masks: nuclear war, murder, morality, politics, and mankind’s more savage impulses. That’s perhaps why the latest films have been some of the smartest blockbusters in recent years.

As Edward Gross says about the Planet of the Apes sequels: “They’re dealing with some heavy stuff.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News