Detecting cancer: why advances in early diagnosis could mark a turning point

Finding cancer early has a huge impact on treatment and survival rates, yet this area has traditionally received far less funding than others. That is changing at last, with increased investment bringing remarkable innovation

Nobody likes to think they may have a serious illness, so it can be tempting to dismiss potentially concerning symptoms as nothing to worry about. But when it comes to cancer, the statistics are stark: if detected early, many types of cancer are easier to treat and people have a higher chance of surviving them.

Before the pandemic, about half of cancers in England were picked up early, helped by national screening programmes for breast, cervical and bowel cancer. But this figure, says Dr David Crosby, head of prevention and early detection research at Cancer Research UK (CRUK), is not where it could be, and has since been hit by the constraints of Covid. “It’s clear that the technologies and systems we currently have struggle to diagnose people with symptomatic cancers, and that’s for a range of reasons – staffing levels, capacity, and symptom awareness among both healthcare professionals and the public – and of course the impact of Covid.

“All these problems need addressing, of course. But there’s a deeper issue, which is that so many cancers don’t actually cause clear symptoms, or their symptoms are vague and hard to recognise. That’s why it’s so absolutely crucial to invest in research to discover the signals of the earliest cancers, and use these insights to develop the technologies capable of detecting them.”

It’s a challenge the research community is starting to rise to. It is increasingly focusing on detecting cancers at ever earlier stages – when they are smaller, less likely to have spread and most easy to treat. But compared with researchers working on cancer drugs, they face a range of hurdles – funding, testing, and the challenges of bringing their developments to market.

When it comes to testing a cancer drug, researchers know that it will be evaluated in clinical trials of people who already have cancer; there is a clear number of steps to follow, and relevant outcomes (does it keep the cancer at bay or extend survival?). There are also well-defined regulatory hurdles to clear. This approach is largely standardised in assessing the safety and effectiveness of a therapeutic intervention.

Top: A patient entering a CT scan; below: Prof Rebecca Fitzgerald

For early-detection researchers, the path is far less certain. They must potentially test hundreds of thousands of healthy people to find those with early cancers, and then follow them for prolonged periods to establish if any cancers have been spotted early enough to make a difference. They also need to be sure their detection method is accurate, with an acceptable rate of downsides such as false positives.

As their research progresses, the route to commercialising an early-detection product, and seeing it put into clinical use, is not well-defined. “So, it’s quite daunting,” says Prof Rebecca Fitzgerald, leader of the Early Detection Programme at the CRUK Cambridge Institute, whose own work focuses on the early detection of oesophageal cancers. “I think that has put researchers off, it has put funders off.”

But early detection is at last coming to the fore, says Fitzgerald, because, for all the advances in cancer therapeutics, survival hasn’t increased as much as many have hoped. This can partly be explained by the nature of advanced cancer – when cancer cells have spread to other parts of the body. By these later stages, cancers have often evolved into a patchwork quilt of different mutant cells, some of which can be intrinsically resistant to treatment, or subsequently become so.

Drug resistance is one of the biggest obstacles in the effort to cure more people of cancer – and arguably the best way to circumvent this is to diagnose cancers before they become too advanced. “Increasingly people realise that we need to be detecting it earlier because the [survival] figures speak for themselves,” says Fitzgerald. And with funding gaps starting to be addressed, she says, more researchers are finally becoming attracted to this field.

Advances in early detection

Fitzgerald herself has invented a device coupled to a lab test – the Cytosponge-TFF3 – designed to pick up Barrett’s oesophagus, a condition that can sometimes develop when the oesophagus has been damaged by acid reflux. This is known to put a person at a higher risk of oesophageal cancer, which is often found too late. If more people with Barrett’s were identified, they could be monitored for signs of cancer, allowing it to be picked up earlier.

The Cytosponge is a swallowable “sponge-on-a-string” that GPs can use in their surgeries, helping them easily spot patients with Barrett’s without the need for an endoscopy, an expensive examination that involves the insertion into the oesophagus of a long, thin, flexible tube with a light and camera.

In a recently published study of 13,000 patients with heartburn enrolled in GP surgeries across England, the researchers found 10 times more cases of Barrett’s oesophagus in patients offered a Cytosponge than in those who were offered conventional investigations such as endoscopy.

The test, which takes 10 minutes to administer, involves a capsule the size of multivitamin attached to a thread. As it is swallowed, the patient or nurse holds on to a retainer card. In the stomach the capsule dissolves to reveal a compressed sponge. When the sponge is pulled back up, it collects cells lining the oesophagus, which are then analysed, using Fitzgerald’s TFF3 lab test, for signs of Barrett’s oesophagus and cancer itself.

Motivated by heavier endoscopy waiting lists induced by Covid, the Cytosponge was rolled out in a pilot in England and Scotland last year. A randomised controlled trial is also being planned to assess whether using the Cytosponge to screen people, and so pick up cancer at an earlier stage, will save lives.

Such early interventions are gaining traction. Measurement technology has progressed to a point where it is now possible to detect tiny traces of molecules in small samples of blood, urine and other bodily fluids, including DNA shed by growing tumours. A blood test has been developed in the US that has potential to detect more than 50 cancers at early stages, including some that are difficult to diagnose early, such as head and neck, ovarian and pancreatic cancers. The test is about to be piloted by the NHS in partnership with CRUK scientists. It will invite 140,000 people with no symptoms who will have an annual blood test for three years. Depending on the study’s outcome, it has the potential to be rolled out to millions in the UK.

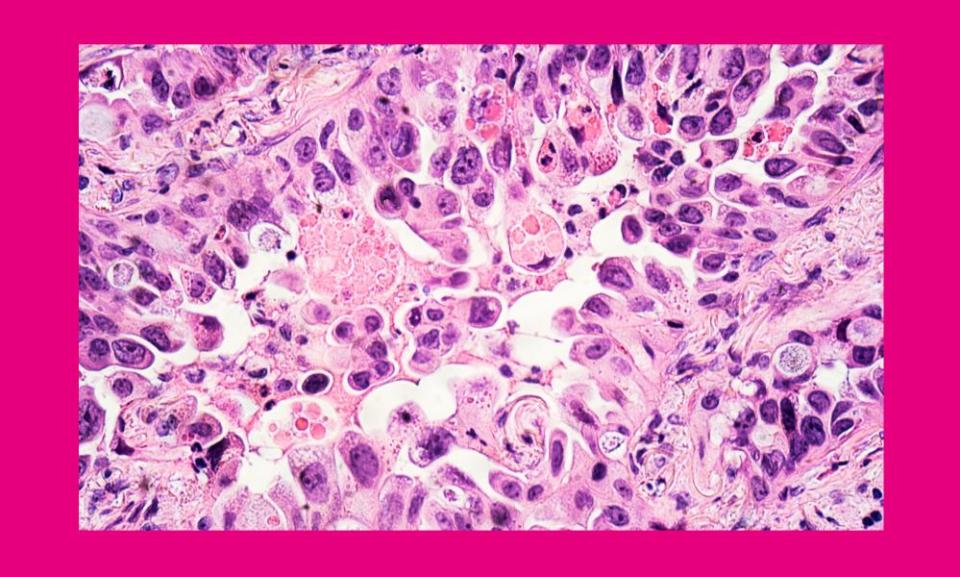

Top: Dr David Crosby; below: adenocarcinoma in the lung

The future of early detection

This comes at a time when scientists are realising that the field of early cancer detection requires not just more funding, but global collaboration between governments, academia and industry to hasten the pace of progress. This has spawned key partnerships such as CRUK’s International Alliance for Cancer Early Detection, bringing together expertise from the UK and the US.

Crosby, who co-authored CRUK’s recent roadmap for the early detection and diagnosis of cancer, points to one particular area of interest in researchers: the large swathes of NHS data that could provide insights into cancer risk at a population level. Access to this information (such as smoking history, BMI, or family history) could help researchers rapidly advance new early detection techniques that can target people at higher risk.

“Then we could target screening at more relevant populations,” he says. “So you’re more likely to help and to target intervention.” Public concern about privacy, he adds, needs to be addressed for this to be possible.

Ultimately, no matter how far biology and technology take us, early detection offers the best chances of good outcomes. “We still need to better understand how to really get the message out there,” says Fitzgerald. “And how do we make these tests really easy, really accessible, just part of normal life? It’s easier to say than do.”

To find out more about the importance of diagnosing cancer early, visit cruk.org/spotcancerearly, or you can support Cancer Research UK’s work in this area by visiting cruk.org/donate

Yahoo News

Yahoo News