What Does the UK Election Mean for Markets, Business and Economy: Q&A

(Bloomberg) -- In a live Q&A on the Markets Today blog, we asked experts from across the newsroom for their analysis of the July 4 UK election.

Most Read from Bloomberg

SpaceX Tender Offer Said to Value Company at Record $210 Billion

Supreme Court Ends OxyContin Settlement, Cracking Sackler Shield

Biden Struggles as He Spars With Trump on Economy: Debate Takeaways

Here is a lightly edited transcript of the conversation. For the latest on everything that matters for UK investors, check out Markets Today.

What is the outcome of the election likely to mean for the UK stock market?

Here’s UK equities reporter Joe Easton’s take:

“Equity investors are generally relaxed about the election’s impact on the broader market, given there isn’t a huge difference in the two main parties’ key policies. That said, the prospect of slightly higher spending under Labour than the Conservatives is seen as a positive for the FTSE 250 index, which is more geared toward the domestic economy than the FTSE 100.

Meanwhile, there are specific sectors to keep an eye on. Housebuilders are seen benefiting from Labour’s pledge to encourage new building approvals, while shares of some of the UK’s smaller energy firms dropped after Labour’s manifesto revealed plans for a £1.2 billion windfall tax on the sector and a vow not to issue new North Sea oil licences.”

And here’s what Cross-Asset Strategist Ven Ram thinks:

“The benchmark FTSE 100 has gained some 7% this year, but even so, the basket is considerably undervalued. With inflation mellowing and the Bank of England itching to cut rates, stocks may continue to be buoyant. A major headwind, though, will be what the new government does with its energy policy, which may sap earnings and weigh on the index. Building companies and banks may, however, fare better.”

Sticking to markets, what could the result mean for the pound?

Ven Ram says:

“The pound is likely to be well supported if Labour comes to power with a clear majority on optimism that a change of guard will augur well for closer ties with the European Union, boosting trade. Currency traders will be particularly receptive to the latter prospect, considering that sterling remains lower by 15% since before the UK voted to leave the EU in 2016. Stickier core and services inflation may also deter the Bank of England to deliver less in rate cuts this year than the markets expect, which will also buoy sterling.”

And what about UK government bonds?

Here’s Ven:

“The outlook for gilts is less clear than that of sterling — simply because it’s far from clear what Labour may do with fiscal policy and government finances if it comes to power. Given that now-infamous mini budget of 2022 that wreaked mega havoc on gilts is still fresh on policymakers’ minds, it’s unlikely that we will get vastly unorthodox fiscal policy.

Front-end gilts are already more than well priced for two rate cuts from the BOE this year, and any disappointment is likely to send yields higher. The 10-year yield is likely to hold above 4% for now as investors continue to demand a significant inflation premium as well as price in uncertainty surrounding the new government’s spending and fiscal plans.”

Bonds and FX reporter Greg Ritchie says:

“A Labour landslide victory has been well-priced by investors for some time now. That means any market impact on such an outcome should be muted. Should the initial results be much tighter than anticipated, that may lead to concern over a hung parliament and political uncertainty. This could weigh on UK assets.”

Speaking of the Bank of England, will the election impact interest rates at all?

Senior UK economics reporter Philip Aldrick says:

“According to the BOE, the election is irrelevant. The June interest rate decision did fall during the campaign but markets were not expecting a move anyway. A first rate cut could come in August, when the bank will also update its forecasts. If Labour wins, as expected, the big change will be the relationship at the top. Governor Andrew Bailey will confer not with Chancellor Jeremy Hunt but with his opposite number Rachel Reeves. Reeves is a former BOE economist.”

Greg Ritchie adds:

“While the BOE stressed last week that the timing of the election was not relevant to its decision, the fiscal choices of a new government do impact the outlook for inflation and growth, which feed directly into the BOE’s interest-rate decisions. That said, the fact neither party’s economic proposals are particularly radical should limit politics’ relevance to monetary policy. Both Starmer and Sunak have said they are confident interest rates will fall should they win the vote.”

And here’s Bloomberg TV’s UK correspondent Lizzy Burden:

“Given that the next government — whatever its hue — isn’t expected to inject a huge fiscal stimulus, the election is otherwise unlikely to slow the pace of rate cuts, though that will become clearer after the first budget, which under Labour would be expected within ten weeks of the election.”

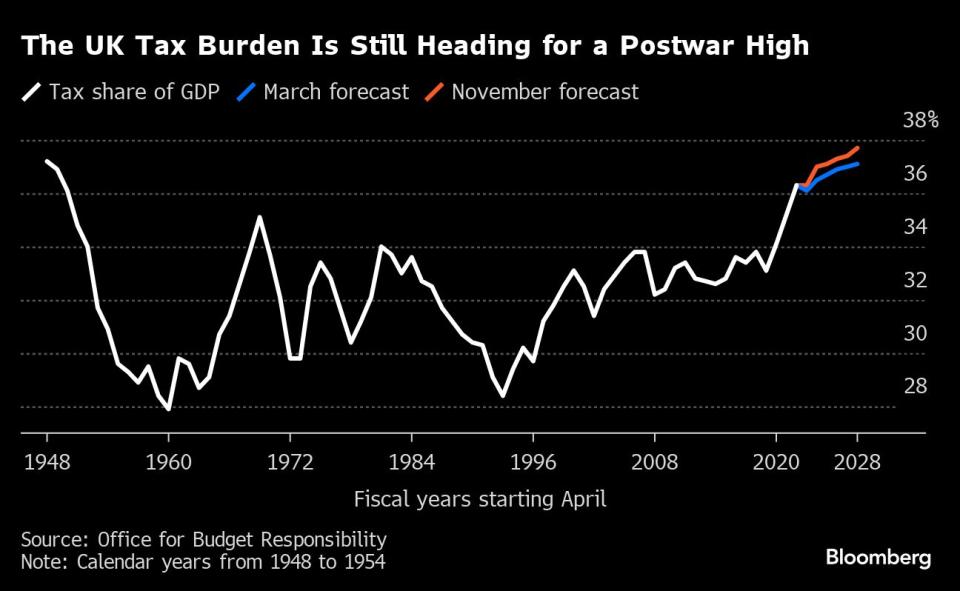

Turning to those fiscal plans, both the Conservatives and Labour say they won’t be raising most peoples taxes, but where might we see hikes?

UK Political Editor Alex Wickham says:

“Speak to pretty much any economist and they say some tax rises are inevitable whoever takes power. Bloomberg Economics reckons the next government needs to find £20 billion of revenue-raisers to deliver current spending plans, let alone do anything else.

Labour insist they don’t see tax hikes as the answer, but privately some aides admit some small rises are likely at the very least. That could mean a focus on wealth - possibly capital gains tax - pensions and businesses. If the growth miracle Labour is praying for doesn’t arrive, more tax rises may be the only way of plugging the spending gap.”

And here’s Lizzy Burden’s take:

“On balance, Labour’s manifesto is net tax-raising while the Conservatives’ is net tax-cutting but neither party will commit to increasing the three main revenue-generating levies: income tax, national insurance or value added tax. The Institute for Fiscal Studies says they are in a “tax lock arms race”.

Both parties also deny they’ll cut spending or borrow more (they saw what happened to Liz Truss). That leaves them in a fiscal bind. If the Bank of England’s growth forecast plays out, the IFS says it would leave a £30bn-a-year fiscal black hole.

So if Labour won’t hike taxes on “working people”, whoever they are (the definition seems to change daily), who would pay? The party has been silent on capital gains tax, inheritance tax, pensions tax, fuel duty and council tax, which leaves them possible targets, though within six months of taking office, Shadow Chancellor Rachel Reeves says she would publish a roadmap for business taxes.”

Here’s Money Distilled’s John Stepek take on what the election’s tax implications might mean for personal finances:

“Assuming you trust the manifestos (and to be clear, the manifestos are perfectly breakable - they are not a binding constraint), there are still plenty of options for a new government (in this case, I’ll focus on Labour as they seem most likely to win, judging by current polling).

Inheritance tax is one - changing the scope of reliefs, particularly the ability to inherit pensions, seems an obvious target and a relatively stealthy one, though it wouldn’t raise a huge amount of money. Revisiting council tax is another option, though this would be a major undertaking and the angry response from the losers would probably be louder than the cheers from the winners.

The scope of VAT could also be widened by getting rid of many more exemptions, not just private schooling. This could in fact be a good thing, as it would represent a tax simplification (no more courtroom battles over the precise confectionary status of Jaffa Cakes, for example) but it might be politically difficult (remember the “pasty tax”?).

I’d also keep a very close eye on what’s being said about pensions. The government could harness pension fund money to its purposes without explicitly raising taxes - you simply mandate various areas where DB pensions need to put their money. Remember this is already being discussed, and with corporate defined benefit pension schemes now collectively in surplus, you’d be daft not to imagine that a new Chancellor won’t be wondering how they can get their hands on said surplus.

But as the team at Capital Economics points out, the easiest way to raise a significant amount of money is simply to break pre-election promises and raise income tax, VAT or National Insurance. Without wanting to give Rachel Reeves ideas, I have a sinking feeling that Labour could easily reverse the “irresponsible Tory NI cuts” and get away with that politically without too much difficulty.”

What could Conservative and Labour tax plans mean for UK businesses?

UK Business Editor Julian Harris:

“The parties’ official tax plans have not provoked any particular concern for businesses, but the worry is what comes next. Labour’s spending commitments are likely to require further tax hikes and Keir Starmer has promised not to lift most personal taxes or to ramp up borrowing. That leaves businesses in the firing line.

At the same time, Labour says it is determined to boost economic growth so may be reluctant to raise levies on companies through fear of harming GDP. It has also said it will reform business rates — the divisive property tax loathed by high street retailers. A move in that direction could prove popular.”

And here’s Alex Wickham:

“Labour has guaranteed it will cap corporation tax at 25%, and would-be Chancellor Rachel Reeves has said she’d be ready to cut the rate should Britain’s competitiveness come under threat from other nations. She’s also said she’ll retain the current government’s full expensing policy.

Keir Starmer put “wealth creation” at the heart of Labour’s manifesto, prioritising boosting investment and working with businesses to unlock economic growth. But if there’s a fiscal black hole and Labour need revenue-raisers, it’s not impossible they will have to look at things like making employers’ pension contributions liable to employer NICs payments. That would yield some £8.5 billion, according to Bloomberg Economics, but would risk upsetting businesses.”

We’ve seen both main parties dial back commitments to net zero goals over the past year. What will their plans mean for businesses and the energy industry?

Alex Wickham says:

“Rishi Sunak’s government made a political decision to move away from a previously pretty pro-green agenda toward much more scepticism over net zero, in an attempt to shore up its core votes among right-wing Tories and voters worried about having to pay more green levies on their cars or gas boilers.

Labour took a different decision to pare back its £28 billion-a-year plan for the green transition to just £5 billion in order to avoid Tory attacks about spending largesse. The energy industry and indeed Labour insiders hope and expect that number to rise again once they’re in office. If it doesn’t, expect questions from industry about the credibility of hitting net zero targets.”

European Power and Renewables reporter Eamon Farhat says:

“Labour’s major plan is to have a fully decarbonized power grid by 2030 a goal the industry says is extraordinarily difficult. Carbon capture technology would have to be implemented to allow gas plants to keep running and an overhaul of the planning system is key to get enough grid upgrades and renewables on the system.

Meanwhile, consumers are going to have to pay up for heat pumps, electric cars and to insulate their homes to meet the goals. That’s going to be an unpopular message to deliver.”

What about utilities? Should we expect to see changes to regulation or water companies like Thames Water taken into public ownership under a Labour government?

Eamon Farhat says:

“A major concern in the UK utility sector is Thames Water, the company that provides water to millions of people in and around London. The company is running down a £2.4 billion funding pile while it seeks new investors — and if this runs out, the company would face being taken into special administration by the government, a form of temporary nationalisation.

The Labour Party said they would not want to take the company into state-ownership over the long-term. There are also concerns that the crisis in the water sector is making the UK into a less attractive place to invest, a view Labour won’t want seeping out.

A closely watched date for the company and the whole industry is July 11. This is when the water regulator Ofwat makes a decision about the five-year business plans that water companies have submitted. They are all hoping to raise bills to fund large investment programs, and for Thames Water, new equity is also needed.”

And here’s Alex Wickham:

“Labour’s likely incoming Business Secretary Jonathan Reynolds told Bloomberg’s Business Debate this week that they wouldn’t want to nationalise Thames Water. That might be a reasonable public line to take as they try to drum up interest from private investors, but many are sceptical that line can hold if things go south and its funding pile runs out. In that scenario, Labour may end up having to put it into “special administration,” a form of temporary nationalisation that may end up costing a bomb.”

What will the parties’ plans to tackle the UK’s housing crisis mean for builders and developers?

Alex Wickham said:

“The Tories have failed badly to reform Britain’s planning system and build new homes, while Starmer has put planning liberalisation and house-building at the heart of his plan for growth. He sees it as a non-negotiable, and he says he’s willing to go to war with vested interest and ‘NIMBYs’ (not-in-my-back-yard) stopping houses from being built.

Expect a raft of quick reforms in the opening weeks of a Labour government: written ministerial statements, statutory instruments and letters from ministers directing local planning chiefs to proceed with projects. They’ll also quickly amend the National Planning Policy Framework to restore mandatory local housing targets at the same level they were before the Tories removed their compulsory element. But privately they admit it’s going to take some time to make good progress on their 1.5 million new homes target for the next parliament.”

Here’s what Real Estate reporter Jack Sidders says:

“Labour has promised to allow construction on some of the uglier parts of the green belt, which it will call “grey belt” areas. This is a politically audacious move that should be a major boon to housebuilders. However, we don’t know how much land will be recategorised or how many homes will be built on it. Overall, Labour’s target of 300,000 new homes per year is not massively high; the UK managed close to 250,000 in the year before Covid.

Nonetheless, Starmer’s pledge to tackle the supply side has improved sentiment among housebuilders, and is one factor behind the sector’s string of mergers and proposed deals of late. There is also some hope that Labour, if they come to power, might mimic the Conservatives’ demand-side policies such as Help to Buy. The scheme was labelled “Help to Bonus” by critics who said it did nothing but raise prices and boost the pay of housebuilding executives — but that won’t worry bosses, let alone shareholders in the industry.”

And Joe Easton‘s take:

“Housebuilder stocks have been hit over the past few years by the jump in mortgage rates, but planning constraints have also weighed on the industry. Labour says it will reinstate mandatory housing targets and appoint hundreds of new planning bosses as as it eyes 1.5 million new homes over a five-year period.

While The Conservatives party announced a similar output target, they’ve generally gone for a demand-side, tax-cutting approach. They’d abolish stamp duty for first time buyers on properties worth less than £425,000, for example.

Equity analysts mostly favour Labour’s supply-side ideas, as demand should rebound anyway if mortgage rates come down as expected later this year. Social housing-focused Gleeson and Vistry are seen as key beneficiaries of Labour’s plans.”

So what does that mean for mortgage holders and those looking to buy a home?

Phil Aldrick says:

“Housing is unaffordable for too many people. To tackle that Labour plans to build 1.5 million homes over five years, which it will deliver by changing planning laws. The Conservatives made the same pledge in 2019 and failed to deliver, and are now promising to build 1.6 million homes over the next parliamentary term. Both parties are also hoping interest rate cuts will help homeowners.

The parties are targeting extra support at first time buyers. Labour will help 80,000 new buyers on to the housing ladder with “Freedom to Buy” mortgage guarantees. The scheme is designed for borrowers with deposits of just 5%. The number of 95% loan to value deals is limited and tend to cost more. The state will guarantee losses up to 20%, making the loan more affordable.

The Tories are raising the stamp duty threshold for first time buyers and providing equity loans of up to 20% of the value of the property under Help to Buy to tackle the same problem of mortgage access.”

What would a Labour government mean for the financial services and banking industry?

Bloomberg’s City Editor Katherine Griffiths says:

“Labour is pinning a lot on getting growth going, for which it wants to secure a wave of private investment alongside public funds. That should mean opportunities in areas ranging from green technology to housing for asset managers and banks.

Labour is planning pension reform, which should make some of that funding easier, but could also challenge established interests among pension funds and insurers who manage a large amount of retirement assets.

The party has said financial services will be key and has promised clear rules, which many believe have been missing for years under the current government. However, those rules will not all be positive for the City of London - Labour has already flagged a tax crackdown on carried interest for private equity firms and its plans to end benefits for non-doms.”

We’ve had a couple of questions through on the implications for M&A activity in the UK, should the polls prove true and Labour win the election.

Here’s what Markets Today’s own Sam Unsted says about that:

“There’s been a sharp rise in M&A interest in UK stocks in the past year or two. That’s been down to a combination of the very cheap valuations the UK stocks trade at compared to indexes in Europe and the US, and a view among potential buyers that this is disconnected from the fundamental value of those businesses.

Post-election, whomever is in government, there’s unlikely to be any change in that dynamic in the immediate term. Should the view that UK politics and policy will become more stable be borne out, then that could change the picture longer term by encouraging more investor flows into UK stocks. More flows might help to narrow the discount on stocks listed in London, making them less attractive for overseas buyers hunting for a bargain.

There’s broad commitment from the main parties on policies around pension reform and encouraging more investment in London stock market that could have that effect. But it’s likely to take some time, not to mention those policies proving successful, to have any tangible impact.”

What will a Labour government mean for the UK’s trading relationship with Europe?

UK Political Correspondent Ellen Milligan says:

“Keir Starmer, who campaigned to remain in the EU, wants to forge closer ties with Britain’s biggest trading partner. He’s eyeing a number of deals: on security cooperation, on checks on fresh food and on allowing certain professions to work more easily in the bloc.

EU diplomats tell me that these are all achievable through negotiation because they tinker around the edges of the Brexit deal and have mostly been previously offered to and rejected by the Conservative government. But that’s also in part because they are limited in ambition. Labour has set three clear red lines on their EU policy: they won’t re-join the customs union, single market or return to freedom of movement.

Their aim is to get as close as possible a relationship with the EU on trade, investment, defence and climate without having to re-open the Brexit deal. Labour aides have conceded to me that they doubt it will unlock the economic growth they’ve promised, but it’s a compromise they’re willing to make to win back Brexit-voting parts of the country and not let Brexit dominate government policy again.”

And here’s Phil Aldrick’s view:

“Labour has promised in its manifesto to “make Brexit work” and “reset the relationship and deepen ties with our European friends, neighbours and allies.”

To secure ensure frictionless trade in food, Labour may accept a role for the European Court of Justice. Jonathan Reynolds, Labour’s shadow business secretary, did not rule out ECJ involvement in an interview with Bloomberg.”

What about trade and inward investment from other countries?

Phil Aldrick says:

“Since Brexit, trade intensity in the UK has fallen behind European peers with damaging implications for productivity and long term growth. On the other hand, greenfield foreign direct investment - overseas money for new projects - has been strong, behind the US but well ahead of Germany and France.

Labour will hope to improve trade intensity and build on solid foreign investment. Its plans for growth need significant amounts of private capital invested in the UK, both domestically and from overseas, and it has co-investment plans to “crowd in” funds by providing public money.”

What are the parties’ attitudes to Chinese companies like fast-fashion giant Shein listing in London?

Joe Easton says:

“The two main parties have been quiet on Shein so far, but they may have taken note of Amnesty International this week describing plans for a London IPO as “troubling,” due to question marks about labour practices. However, it would be unprecedented for the government to intervene on ESG grounds. Likewise, the UK regulators and London Stock Exchange itself are not in a position to prevent a listing based on ESG.”

And Alex Wickham adds:

“China and the UK economy has been a thorny political issue for several Tory governments weighing the need for foreign investment with national security and human rights concerns. Those same questions will exist for Labour.

So far, we’re hearing a pretty welcoming stance from the likely incoming government on issues like Shein — Shadow Business Secretary Jonathan Reynolds told Bloomberg this week that having them list in the UK means they can be regulated to British standards, so in other words he’s keen on the listing. Others in Labour may point out that allegations about its practices in China don’t sit easily with the party’s push for better workers’ rights.”

Most Read from Bloomberg Businessweek

The FBI’s Star Cooperator May Have Been Running New Scams All Along

RTO Mandates Are Killing the Euphoric Work-Life Balance Some Moms Found

Japan’s Tiny Kei-Trucks Have a Cult Following in the US, and Some States Are Pushing Back

How Glossier Turned a Viral Moment for ‘You’ Perfume Into a Lasting Business

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News