‘You can expect everything’: what next for Julian Assange and WikiLeaks?

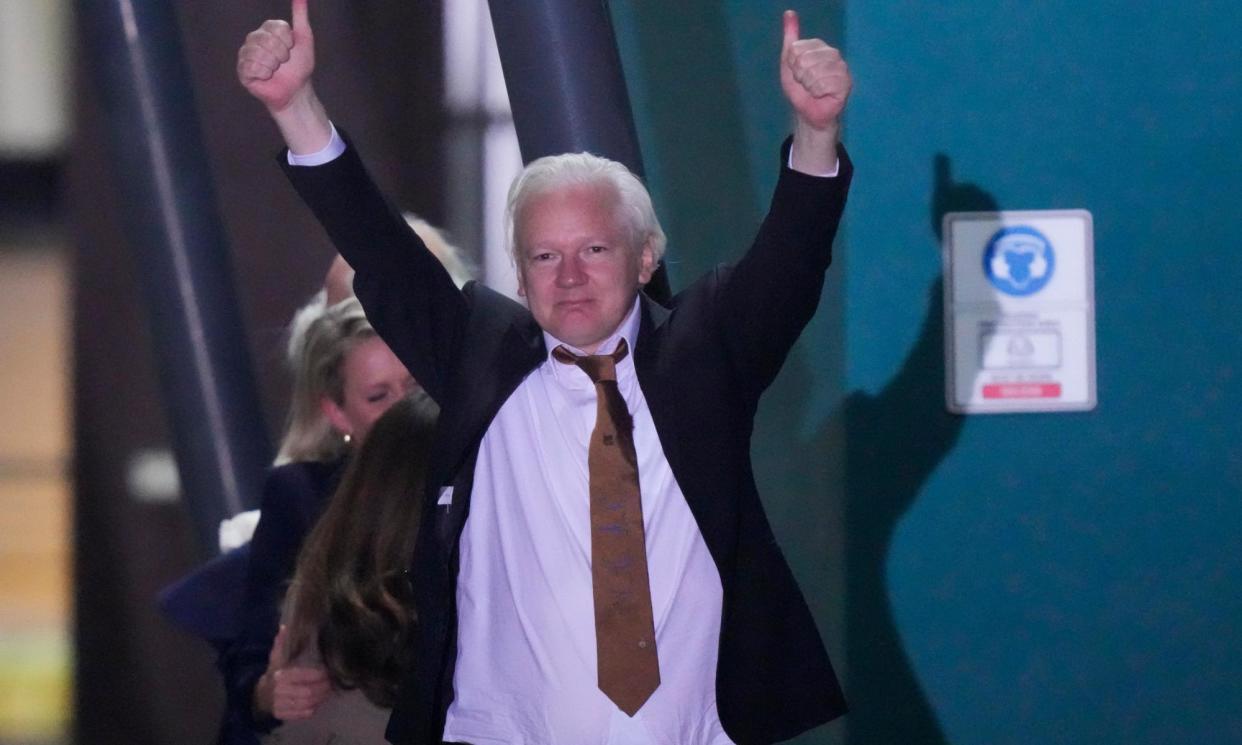

As Julian Assange enjoys his first weekend of freedom in years, there appeared to be no question in the mind of his wife, Stella, about what the family’s priorities were.

The WikiLeaks co-founder would need time to recover, she told reporters after they were reunited in his native Australia, after a deal with US authorities that allowed him to plead guilty to a single criminal count of conspiring to obtain and disclose classified defence documents.

What comes after that is one of the most intriguing questions for anyone familiar with how the site he founded in 2006 utterly changed the nature of whistleblowing. Will it return to its original mission?

While it remains online – and would-be whistleblowers can theoretically use it to pass on secrets – to all intents and purposes the organisation around it has been repurposed in recent years to campaign for Assange’s freedom.

Assange himself told the Nation magazine in an interview inside Belmarsh prison, London, that it had not been possible to publish leaks due to his imprisonment, surveillance by the US government and funding restrictions.

Other issues are also starkly unavoidable, not least the fact that the type of encryption technology and other processes which WikiLeaks in many ways pioneered now exist in every good news organisation.

James Harkin, the director of the London-based Centre for Investigative Journalism, said interest in WikiLeaks – which he characterised as “a loose alliance between investigative journalists and information anarchists” – emerged more than a decade ago from a profound frustration with the mainstream media’s inability to report what western states were really doing in places like Afghanistan and Iraq.

It was one reason the centre loaned Assange and WikiLeaks some of its time and interns – the site was doing something fresh.

But he added: “Now some of those lessons have been learned. The kind of cross-border, collaborative investigations into huge tranches of documents that WikiLeaks pioneered and its use of anonymous electronic information drops are now de rigueur – to a large extent passé.”

“In retrospect, it’s striking that everything WikiLeaks published was true – no small feat in the era of “disinformation” – but the tragedy is that much of its energy and ethos has now passed to blowhards and conspiracy theorists. Perhaps, in the light of our tepid new involvements in the Middle East and Ukraine, we need a new WikiLeaks.”

Another problem for many relates to some of the company kept and alliances formed by Assange, a mercurial character who has had his fair share of falling-outs – including with the Guardian. Before entering the Ecuadorian embassy, he had started hosting interview shows for RT, the Russian state media outlet, in a move that was relatively easier to defend at the time but which now takes on a different hue since the outbreak of the Ukraine war.

That said, even some critics of Assange suggest that there may be a role for WikiLeaks, with or without him onboard.

James Ball, a journalist and former WikiLeaks staff member, said “the smart move” would be for Assange and WikiLeaks to become a figurehead for transparency activism.

“It’s difficult to see how they can return to what they were doing before. They were well ahead of the curve originally, but frankly they became sloppy and there was a problem of inexperienced volunteers coming in and out, with people not being vetted,” he added.

“People around him have said that it’s taken a toll on his health and I’m sure he’ll want to catch his breath, so if he wanted a quiet life that would be understandable.”

While much of the WikiLeaks public output has been focused on Assange’s predicament, the site has continued to maintain a presence as a platform for amplifying the journalism of others.

As recently as this week, its X account was promoting the Gaza Project – a collaboration involving journalists from 13 different news organisations investigating the killing of journalists in Gaza.

As well as this, the ripples of its original leaks continue to have an impact in big and small ways. This week, in the UK, the populist rightwing Reform party dropped one of its election candidates after it was revealed that he had been named on a list originally leaked to WikiLeaks that showed the membership in 2016 of the far-right British National party (BNP).

Whatever happens, few who known him expect Assange to spend the rest of his life on an Australian beach.

Stefania Maurizi, a London-based Italian journalist who has worked as a media partner of WikiLeaks since 2009, emphasised what she described as the “exceptional resilience and determination” of the organisation and its founder.

She said that she would understand if Assange and the WikiLeaks journalists wanted to move on, adding: “They have given and sacrificed so much, while he and Stella deserve to enjoy their life with their kids.

“At the same time, many times in the past WikiLeaks has been considered dead, gone, and yet it is still making headlines around the world. You can expect everything from Julian Assange and WikiLeaks.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News