Exposure to sheep could trigger multiple sclerosis, study suggests

Exposure to a toxin primarily found in sheep could be linked to the development of multiple sclerosis, a new study suggests.

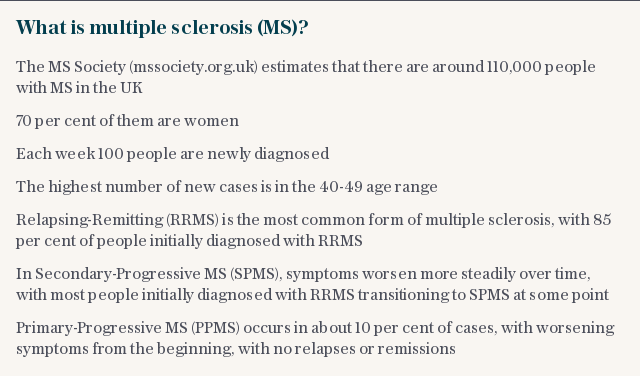

More than 100,000 people in Britain have been diagnosed with MS, which occurs when the immune system attacks the protective coating surrounding nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord.

The condition leads to inflammation, pain, disability and in severe cases, early death, but experts still do not know the underlying cause.

Now researchers at the University of Exeter have discovered that nearly half of the MS sufferers that they studied had been infected at some time in their lives by epsilon toxin.

The toxin is produced in the gut of sheep by the Clostridium Perfringens bacterium and can also be found in the soil.

Researchers looked at 250 people - half of whom had MS - and found 43 per cent of MS patients were carrying antibodies to epsilon toxin, proving it had been in the body long enough for the immune system to produce a response.

In comparison just 16 per cent of people without MS had been exposed.

“Our research suggests that there is a link between epsilon toxin and MS,” said Professor Rick Titball, of the University of Exeter.

“The causes of MS are still not fully understood and, while it’s possible that this toxin plays a role, it’s too early to say for certain.

“More research is now needed to understand how the toxin might play a role in MS, and how these findings might be used to develop new tests or treatments.”

MS was first recognised in the 1860s and it has long been established that it is more common in northern, less sunny climates, giving rise to theories that the condition could be triggered by a lack of Vitamin D.

But MS is also more common in latitudes and countries where sheep populations are high.

The researchers say people could become infected with the toxin from being near sheep, and the bacteria can also produce spores meaning it can travel for long distances in the air. It is unlikely to be caught through eating lamb however as the cooking kills the toxin.

The university embarked on the study with life sciences company MS Sciences Ltd after hearing that some MS patients in the US had tested positive for epsilon toxin antibodies.

Experts have suggested that the immune system may overreact to the toxin, or fail to turn off, leading it to begin attacking healthy cells in the body.

Trials in the US have shown it is possible to effectively cure some people of the condition by rebooting the immune system using chemotherapy drugs.

But if it can be proven that the condition is caused by a bacterial toxin then a vaccine could be created to inoculate people against ever getting MS, in the same that people are given shots against tetanus.

“We are confident that these significant findings from our latest study will help people get even closer to an answer for the elusive triggers of MS,” said Simon Slater, Director of MS Sciences Ltd.

“If the link between epsilon toxin and MS is proven, then this would suggest that vaccination would be an effective treatment for its prevention or in the early stages of the disease.

“Interestingly, although epsilon toxin is known to be highly potent, no human vaccine has ever been developed.”

MS, most commonly diagnosed in people in their 20s and 30s, and the majority of people who are diagnosed with the condition are told they have relapsing MS. Around half of those patients will develop secondary progressive MS within 15 to 20 years.

Dr Sorrel Bickley, Head of Biomedical Research at the MS Society, said: “There’s still a lot we don’t know about the cause of MS, which affects over 100,000 people in the UK.

“Research into environmental and genetic factors is important, and this study gives us some new clues, but it’s only a small part of the story.

“More research will be needed before we can truly know why people develop MS, which is why we’re funding research to better understand the cause and develop new treatments.”

The research will be published in the Multiple Sclerosis Journal.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News