First 'Twins' of Mysterious Erupting Star Found

A strange star that threw off huge amounts of gas and dust in a mammoth eruption more than 150 years ago isn't such an anomaly anymore.

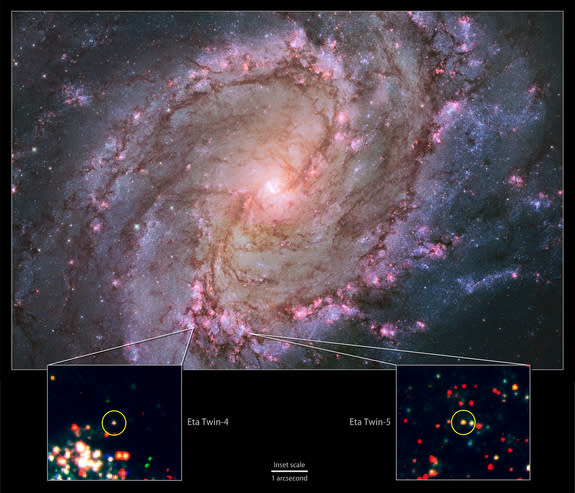

Astronomers have found five objects beyond the Milky Way galaxy that resemble Eta Carinae, a binary system composed of two enormous stars that lie 7,500 light-years from Earth. The larger of these two stars blasted out about 10 times the mass of the sun during a mysterious eruption in the 1840s, and the expelled gas and dust still cloak Eta Carinae like a veil.

No objects resembling the Eta Carinae system have yet been found in the Milky Way. But researchers searching farther afield have now spotted five Eta Carinae-like systems in four different galaxies. [Visualization of the 'Great Eruption' Eta Carinae Nebula (Video)]

"We knew others were out there," co-investigator Krzysztof Stanek, a professor of astronomy at Ohio State University, said in a statement. "It was really a matter of figuring out what to look for and of being persistent."

Eta Carinae is the brightest and most massive star system within 10,000 light-years of Earth; it is about 5 million times more luminous than Earth's sun. Astronomers think the two stars in the system, which circle a common center of mass on a 5.5-year orbit, are about 90 times and at least 30 times more massive than Earth's star, NASA officials said. The bigger star will likely die in a supernova explosion at some point in the not-too-distant future.

"The most massive stars are always rare, but they have tremendous impact on the chemical and physical evolution of their host galaxy," lead scientist Rubab Khan, a postdoctoral researcher at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, said in the same statement.

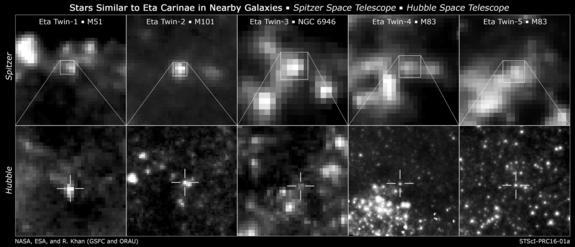

The Eta Carinae system offers clues about the evolution of massive stars and how they affect their surroundings, but there are limits to what can be gleaned from a single example. So Khan and his colleagues came up with a sort of spectroscopic fingerprinting system that could identify stars that have experienced massive eruptions recently, and then they began searching the heavens using NASA's Hubble and Spitzer space telescopes.

"With Spitzer, we see a steady increase in brightness starting at around 3 microns and peaking between 8 and 24 microns," Khan said. "By comparing this emission to the dimming we see in Hubble's optical images, we could determine how much dust was present and compare it to the amount we see around Eta Carinae."

This strategy turned up no candidate "Eta twins" during a seven-galaxy hunt from 2012 through 2014 .But a follow-on search in 2015 found two such systems in the galaxy M83, which lies 15 million light-years away, and one each in the galaxies NGC 6946, M101 and M51, which are located 18 million, 21 million and 26 million light-years from Earth, respectively.

NASA's $8.8 billion James Webb Space Telescope, which is scheduled to launch in late 2018, should be able to determine if these five objects are indeed true Eta twins — massive stars surrounded by huge amounts of gas and dust — NASA officials said.

The new study was published last month in The Astrophysical Journal Letters. Khan also presented the team's findings Wednesday (Jan. 6) at the American Astronomical Society's 227th Meeting in Kissimmee, Florida.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Copyright 2016 SPACE.com, a Purch company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News