The German who taught England to love itself

Like a greedy boy at prep school receiving a cake through the post, my eyes widened whenever I got hold of a new county volume to devour in the Buildings of England series, familiarly known as Pevsner.

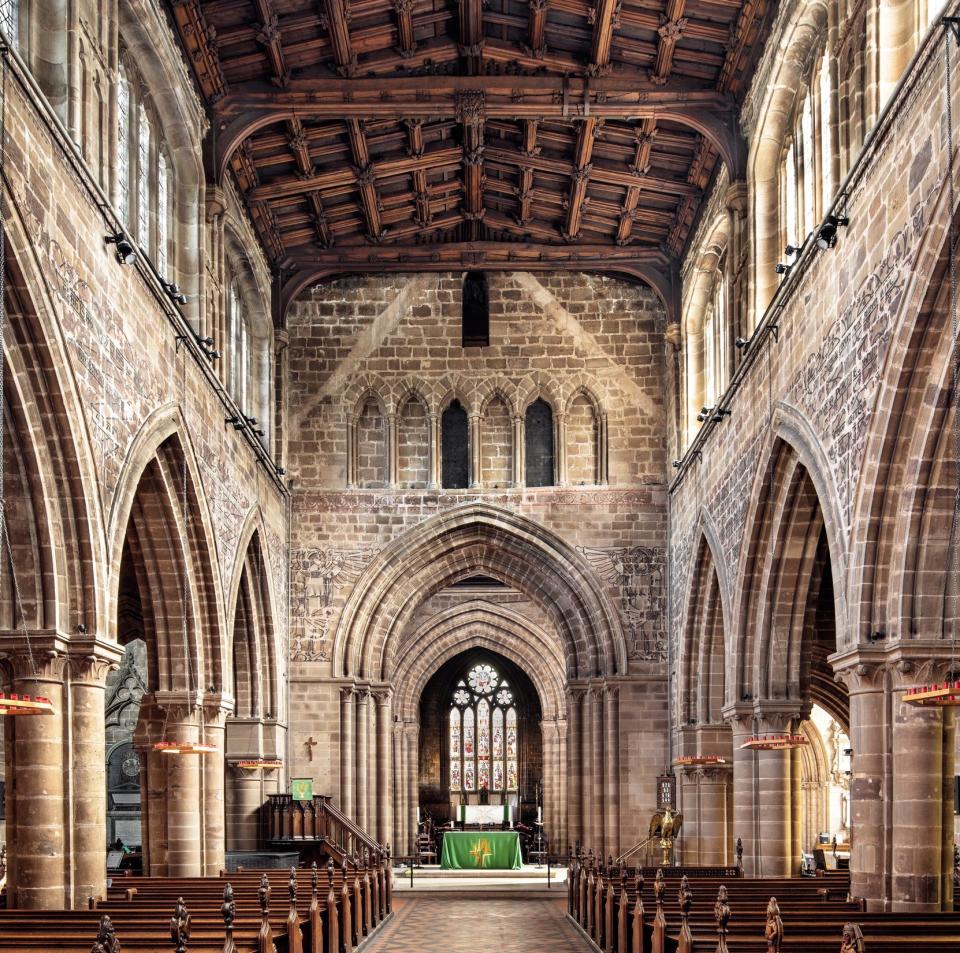

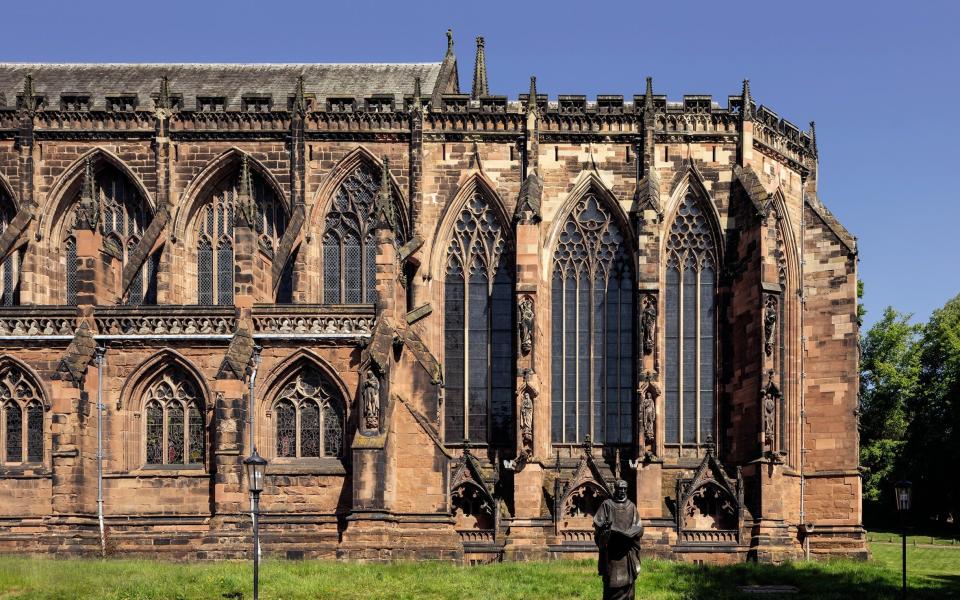

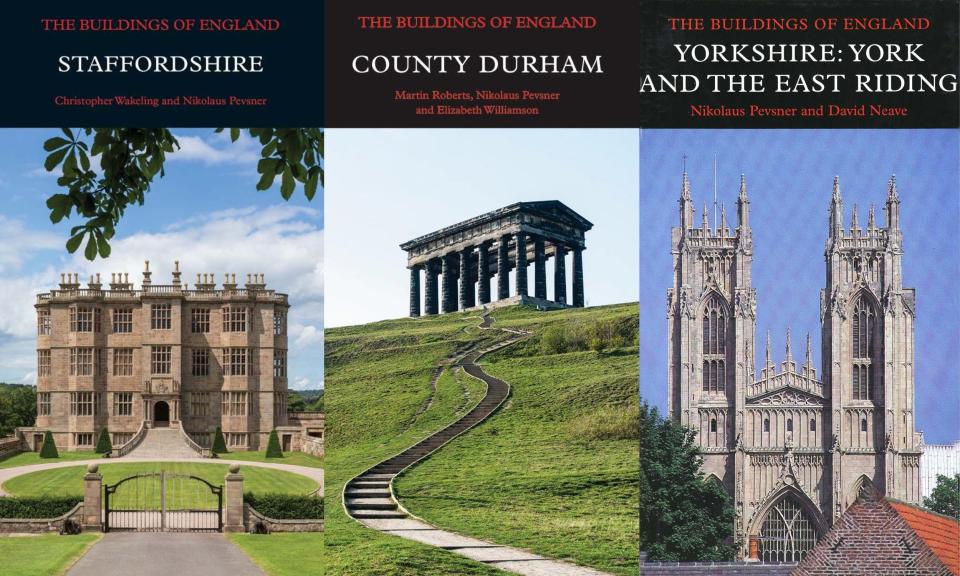

Now I have the new Staffordshire in my hands and I yearn to test drive it – to be off to Cheadle to see the spire, “one of the most perfect pieces of 19th-century Gothic Revival anywhere” (in a phrase preserved from Nikolaus Pevsner’s first edition of the guide in 1974).

I want to see the curious bas-relief on Samuel Johnson’s memorial in Lichfield and the monument in Rugeley Old Church to Thomas Lander (1670), with “his corpse in a winding sheet, as if it were a hammock”. Staffordshire is the last of the 56 revised and amplified volumes in this stupendous series. There are no more volumes to come like food parcels.

The Hercules who laboured over the series from 1951 and taught England to love its villages and towns, was not home-grown but born in Leipzig, fleeing in 1933, aged 31.

It was not until the end of the Second World War that Nikolaus Pevsner suggested an impossible project to Allen Lane, the genius behind Penguin Books. The plan was for him to visit and record every building of architectural significance in England and publish a guide to them county by county. He did it.

If it was a monument to thorough German grit, it was also, I feel, as English as the buildings he described. Nothing like the Pevsner series exists in any other country. But it resembles other British multi-volume enterprises, such as the Dictionary of National Biography, begun by Virginia Woolf’s father, or the Oxford English Dictionary, heaved into motion by Sir James Murray – who did not live to see it completed.

The Pevsner discipline was relentless. An assistant would spend a year researching sources for a county and filing the findings alphabetically under parish place-names, and then, in long days from 7am to 10pm, he would drive Professor Pevsner so he could view and record churches, manor houses, public lavatories. Pevsner did not drive. His wife Lola, like Clement Attlee’s wife, acted as chauffeur until her death in 1963.

Michael Taylor, the assistant for Warwickshire in 1965, left a painfully comic account of dismal lodgings and dreadful meals. (“I think he could have eaten sawdust.”) He was not paid but had to pay his own expenses.

I had not realised how theatrical Pevsner’s diction was until I read the comedy of embarrassment in the tale of chauffeuring the Professor down a half-mile drive to inspect the facade of a grand house, only to find that, on the lawn around which the drive looped, two women in pre-war bathing costumes were sitting on the grass, beside a man in a blazer and a butler witha tray of drinks.

The only way out was forward, but Pevsner cried out: “Slow down, slower my darling, three storeys, Dutch gables, central Venetian window first floor, my darling slow down.” By then they were 10ft from the group, moving at less than walking pace, while the group stared, “stunned by our contemptuously slow passage”. The Professor remained engrossed in his facade and clipboard and his exhortations to be still slower. Even the butler turned to follow their slow progress, while sweat poured off Taylor’s scarlet face.

In 1974 the clear-eyed Pevsner, by then Sir Nikolaus, wrote in the introduction to the last volume: “It is the second editions which count.” The second edition volumes are fatter, in larger format than the original pocket-books and contain 7,061 illustrative photographs in which the world has blossomed from black and white into colour.

The statistics are astounding: 225,000 buildings and memorials described in 44,890 pages or 20 million words. Scotland and Wales have their own series. Most impressively, 135 contributors have taken part in this national endeavour without it breaking apart.

It was a close run thing. By the 12th volume, Penguin had lost £36,000 on the endeavour, and Lane only saved it from destruction by finding charitable funds. Yale rescued the enterprise when Penguin quailed. The Paul Mellon Foundation became its chief benefactor. And all so that we can put a volume in the car when we’re visiting people for the weekend in Herefordshire.

Does Pevsner tell us what to think, as Baedekers told EM Forster’s characters in Florence? No, generally I think he makes readers look at things and make up their minds. “His curiosity about how a building achieves its effects remained unquenched even when he disliked the result,” commented Bridget Cherry, who edited the series from 1971 to 2002.

“He was not dry and precise; he was precise and enthusiastic, even at times exuberant,” remembered Michael Taylor. Partly because of the showmanship of John Betjeman, Nikolaus Pevsner is often unfairly regarded as a champion of Modernism and an enemy of Victorian architecture. Yet he chaired the Victorian Society, and his readers had to catch up with his taste for that era.

As for Modernism, he liked the International Style of the 1930s and was surprised by a radical change, heralded in 1934 by London Zoo’s penguin pool by Berthold Lubetkin – eventually abandoned because his concrete slopes gave the penguins sore feet. If Pevsner found the Victorian architect William Butterfield aggressive, he found modern Brutalism more so, and called James Stirling’s History Faculty building at Cambridge (1968) “anti-architecture” and “actively ugly”.

The new Staffordshire reprints Pevsner’s short essay on finishing the series first time round. In 1974, he declared that towns were now marked by “high blocks of flats, often unneeded and nearly always unwanted by those who have to move into them, and by speculative centre renewal, ie usually shopping precincts”. Fifty years on, those elements have ruined our high streets and produced disastrous housing estates.

What now for Pevnser? Simon Bradley, the series editor who has worked on it for 30 years (longer than Pevsner’s labours on the first edition) told me of an initiative that will revolutionise the volumes. It is simply to put them online.

Of course it is not so simple. Will each architect and squinch be given a hypertext link to examples in other counties? But to me, putting Pevsner online promises to add as much to its value as constructing an online Oxford English Dictionary did.

Bradley, himself a tireless encyclopaedic enthusiast, sees his career-long association with the series as a kind of patriotism (extended to Scotland, Wales and Ireland, which now have their own Pevsners).

He has taken on volumes requiring the greatest knowledge: the City of London, Westminster, Oxford, Cambridge. I’m surprised he is not, like the Professor, a knight. But he’s not even in Who’s Who.

Pevsners are not Baedekers giving starred ratings, but they are guidebooks. Will there continue to be an educated market for them? There are signs of hope, parallel to the growth of interest among the young in the stories of the heroes of D-Day. Buildings in landscapes are the things that people will want to understand if they wonder what makes England English, which was Nikolaus Pevsner’s fascination when first he reached these shores.

The new Pevsner guide to Staffordshire is available from June 25; £45, yalebooks.co.uk

Yahoo News

Yahoo News