Gladstone’s legacy is murky – my university shouldn't glorify it

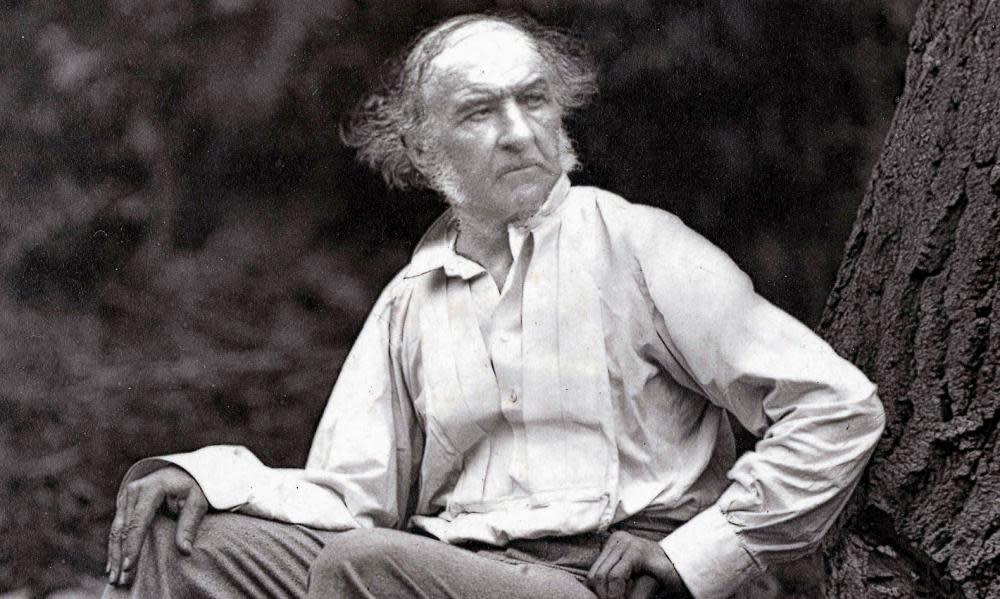

My friend Alisha Raithatha and I both used to live in Liverpool’s Roscoe and Gladstone student halls of residence. We came to dislike the name. The building is of course named after former prime minister William Gladstone, who used parliament to defend his father’s treatment of slaves, to secure some of the biggest pay-outs in slavery reparations, and to sanction forced labour post-abolition. We didn’t think he deserved to be honoured above our door.

That’s why my friends and I launched a petition: to give students an opportunity to change the building’s name and to start a conversation about slavery’s legacy in Britain. The halls are being refurbished, so it seemed a good opportunity for change. In a world where contemporary slavery continues to affect some 3 million people and where racism continues to blight society, we believe celebrating those who aided it is wrong.

We’ve been met with predictable criticism. Most often, Gladstone’s defenders will cite his political successes and the ubiquity of racism in the 19th century. But this is whataboutery, not a direct answer to our questioning of his actions. We mustn’t forget that his first parliamentary speech was a defence of the trade of human beings. Naming a building after Gladstone risks glorification as it doesn’t give due weight to his moral flaws.

Elsewhere, newspaper commentators who hit back at us with words like “erasure”. I doubt their sincerity, given their long-running attempts to try to silence young people on issues of race. A vicious media campaign was recently launched against activist Lola Olufemi, for merely asking to include more BAME writers on her English course. And Jason Osamede Okundaye, another Cambridge student, was subjected to a media pile-on after a supposedly controversial tweet. If students hadn’t spoken up, these mainstream discussions of race wouldn’t be happening at all. So much for erasure.

As a society, we have yet to get to grips with our imperial past. It makes what should be a reasonable argument considered divisive. On campuses, students like my friends and I can start to change things and contribute to the historical narrative. We should be able to kick up a fuss, put plaques on walls and write small petitions. Why? because history belongs to us too, and we should have a say as to who we get to honour and celebrate.

Our campaign makes no apologies about being emotional about slavery. Because it is insincere to expect only cold rationality about one of the darkest episodes of our past. We’re passionate, and we’re not ashamed of it.

Our petition suggests the university building should be instead named after university alumni, or hold a plaque which provides greater context to the Gladstone name. Liverpool has decided to hold a university-wide poll, so hopefully students will better feel they have a say. Whatever happens next, we are proud of starting a rare conversation about the legacy of slavery in Britain.

Tinaye Mapako is a student at the University of Liverpool

Follow Guardian Students on Twitter: @GdnStudents. For graduate career opportunities, take a look at Guardian Jobs.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News