The Guardian view on rising sea levels: a warning from Greenland

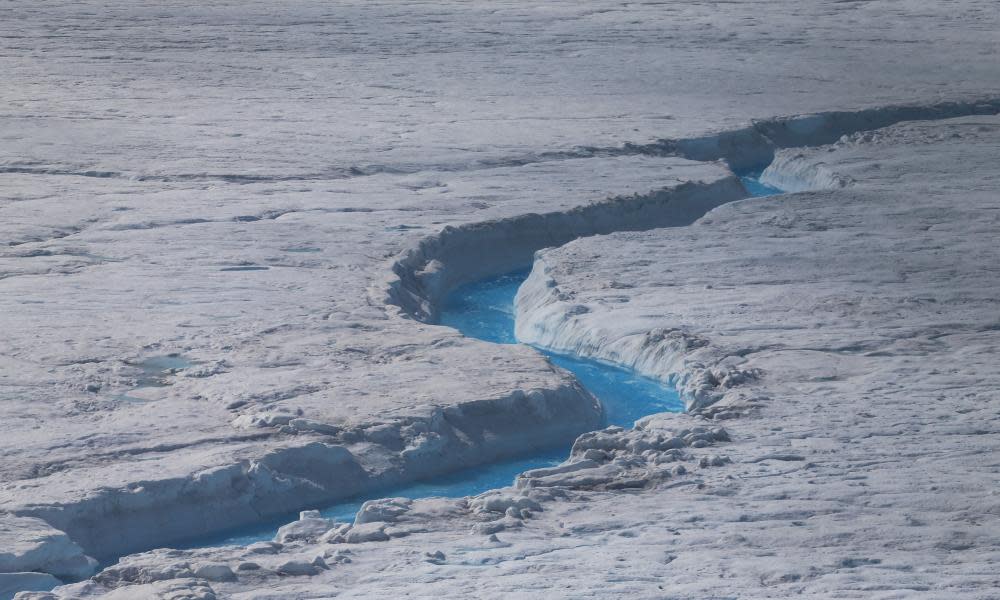

Dramatic increases in the rate at which ice on Greenland and East Antarctica is melting are, along with the heatwave gripping Australia, among the latest manifestations of the changes our planet and its atmosphere are undergoing. Concerns surrounding the risk of melting ice causing sea levels to rise were previously focused mainly on large glaciers. But scientists have discovered that the largest recent losses from Greenland’s vast ice sheet, which is two miles thick in places, have occurred in the island’s largely glacier-free south-west. Combined with recent analysis of retreating Antarctic glaciers that were previously thought to be stable, this new research makes unnerving reading. This is because of what it tells us about the extent of likely sea level rises, and warming seas linked to coral die-off and chaotic weather, but also because it highlights the difficulty of fully understanding the climate system.

Last year the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change urged governments to work towards the most ambitious targets in the 2015 Paris agreement, and a global temperature rise not greater than 1.5C. Many experts fear that factors including the election of Donald Trump in the US and Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil mean that even the more modest goal of sticking to current commitments, putting the world on course for a 3C rise, remains a huge challenge. Currently, global carbon emissions are still rising. But if people all over the world are getting used to the idea that higher temperatures and increased frequency of extreme weather events are the new normal – recent polling in the US suggests 72% of Americans believe global warming is important, the highest-ever figure – we are arguably less advanced in our understanding of warming oceans.

The sea level rises that scientists expect to accompany a temperature rise of 3C would submerge cities including Shanghai, Osaka and Miami along with parts of Rio de Janeiro and Alexandria – less than a century from now. Among nations, Bangladesh will be particularly severely affected, with one estimate suggesting that 250,000 people are already forced to move each year, making them environmental refugees. Such facts on the ground, as well as predictions, are why climate activists have long linked their cause to wider concerns around social justice. Just as carbon emissions must be limited to protect the livelihoods of people already struggling in areas vulnerable to drought and desertification, sea level rises must be restricted to protect the millions of people who live on coasts and in low-lying areas. The movement of peoples around the world, including but not limited to refugees, is in some cases a direct consequence of changes to the environment.

Weather and climate systems are complex, and sea levels are hard to predict confidently. Already, ice sheets and glaciers are surprising scientists by behaving in unexpected ways. But while trying to limit future emissions remains the most pressing task, these ominous findings highlight the need to address the consequences of carbon already emitted. Sea level rises will continue long after emissions have peaked. We will have to adapt to our world’s changing shape.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News