Hassan Nasrallah: the man who has led Hezbollah to the brink of war with Israel

Twenty-four years ago, on 26 May 2000, Hezbollah’s general secretary, Hassan Nasrallah, arrived in the small Lebanese town of Bint Jbeil a few kilometres from the Israeli border.

The day before, Israel had withdrawn its forces from southern Lebanon after a years-long occupation in which it was harried by Hezbollah and other groups. Thousands of supporters gathered there under Hezbollah’s yellow banners.

The cleric, then 39 and wearing his familiar black turban and a brown robe, gave one of the most famous speeches of his career.

Addressing the Arab world and the “oppressed people of Palestine”, Nasrallah claimed that Israel was “weak as spider’s web” despite its nuclear weapons. The themes in his speech that day would come to define Nasrallah’s worldview in the decades that followed, fusing notions of Shia theology and liberation rhetoric, and founded on the belief that authentic resistance can overcome a far superior military force.

Since then Hezbollah has been transformed, both as a fighting force and in its relationship with the fragile Lebanese state, becoming a political and social powerhouse. But while Nasrallah’s rhetoric may have remained unchanged, his appreciation of the fragility of power, even for the world’s most powerfully armed non-state actor, has mutated and he has led Hezbollah to the brink of its potentially most serious conflict. It has sent rockets and drones into Israel, as Israel hits Lebanon and Hezbollah targets with airstrikes.

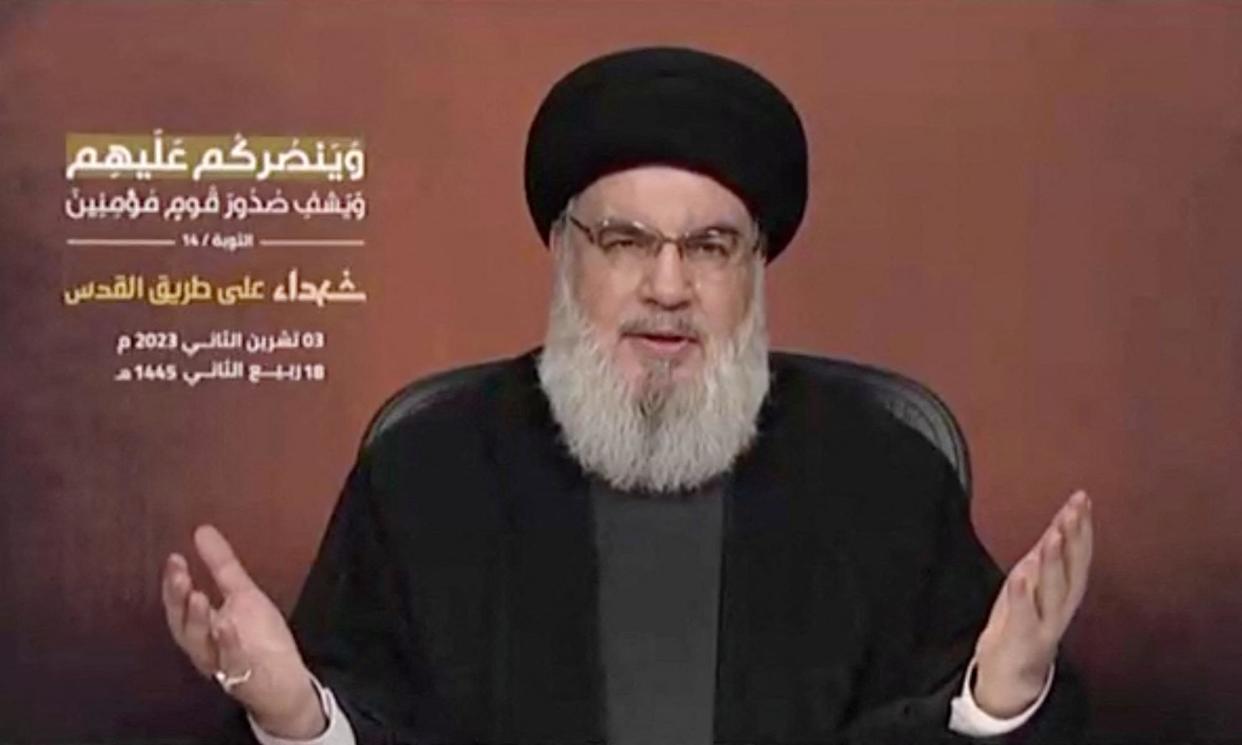

When Nasrallah makes a speech these days, it is not before the huge crowds that once greeted him, arriving in buses from Lebanon’s Shia heartlands. At carefully choreographed events, including memorial services for fallen Hezbollah commanders, Nasrallah appears not in person, but on a television screen. At one such event earlier this year, Hezbollah MPs in attendance explained to the Guardian, as they declined to comment, that Nasrallah’s words were not to be interpreted by them. For everyone else, however, Nasrallah’s long and often repetitive speeches have become the subject of endless exegesis in the past eight months of war in the Middle East.

While often painted as Iranian proxies, Nasrallah and Hezbollah are more than that. They are important regional players in their own right, despite the deep connection to Tehran.

And as Israel and Hezbollah have drawn ever closer to all-out conflict, two questions have collided: what does Nasrallah want, and how far is he in control of any outcome?

Nasrallah’s policy in the first weeks of the cross-border clashes that began on 8 October, a day after Hamas’s surprise attack on southern Israel, was ostensibly designed to relieve pressure on the Palestinian armed group in Gaza, a strategy that appears to have been more significant on the diplomatic than on the military front.

By explicitly making any demand to stop firing on Israel’s north contingent on an end to Israeli hostilities in Gaza, Nasrallah has woven in outstanding territorial issues on the Lebanese border including over the Israeli-occupied Shebaa farms, which Syria also claims, while framing the fighting in terms of a wider rejection of US-led policies in the Middle East.

The reality on the ground has created a far more complicated picture.

Related: The Guardian view on Israel and Hezbollah: the gathering storm endangers the region | Editorial

In casting aside the status quo between Israel and Hezbollah that held since the end of the month-long second Lebanon war in 2006 that brought huge destruction to Lebanon, Nasrallah has rolled a dice. It belies the deliberate ambiguity of his statements, which hover between threats to Israeli cities and the insistence that his group does not want all-out war.

“To some extent, what Hezbollah has been doing,” Heiko Wimmen, the director of the International Crisis Group’s Iraq, Syria, Lebanon project, told the New Arab in the first weeks of the war, “is to underline that they are ready to pay a price.

“But are they ready to pay the ultimate price? Nobody knows that because this is part of the constructive ambiguity mentioned by Nasrallah.”

In the subsequent months the escalating dynamics of the war have stretched the considerations that saw Nasrallah enter the conflict, to breaking point. A “managed conflict” has become increasingly unmanageable as Israel has targeted senior Hezbollah officials and Hezbollah has fired on Israeli military and civilian targets, and more recently threatened Haifa and other cities.

“It’s important to understand Hezbollah’s worldview,” said Sanam Vakil, the director of the Middle East and north Africa programme at Chatham House. “What many actors like this are good at is understanding adversaries through quiet repeated and deliberate observation … strategic patience is part of their outlook: knowing that adversaries have different pressures in democratic societies.”

Nasrallah has cited US opinion polling on Israel’s war in Gaza as evidence of the success of his broader strategy. “I think it is also key to understand that while Nasrallah’s leadership is very personal, the effectiveness of the organisation is that it’s not run as a personal fiefdom,” Vakil said, suggesting it would survive his removal.

She also expressed doubt that assumptions prior to the current conflict about Nasrallah and Hezbollah’s appetite for conflict held true as the war has reduced the room for both sides to exit an escalation. “We are making a lot of guesses and assumptions, but we’re not accessing the inner network to understand the decision-making processes.”

Nasrallah’s ideological origins

What is clearer is how Nasrallah’s worldview has been shaped by his personal history. A teenager amid the sectarian violence of the Lebanese civil war, he briefly joined the Shia Amal militia at 15 before going to study at a seminary in Najaf, Iraq from where he was expelled with other Lebanese students by Saddam Hussein in 1978.

Under the influence of his mentor, the prominent cleric and co-founder of Hezbollah Abbas al-Musawi, who he first met in Iraq, he joined Hezbollah in 1982 after Israel’s invasion of Lebanon, when the group split away from Amal. When Israel assassinated Musawi in 1992, he replaced him as Hezbollah’s general secretary.

In an interview in 2006 with Robin Wright of the Washington Post, Nasrallah described how his beliefs had been forged as he and his peers watched “what happened in Palestine, in the West Bank, in the Gaza Strip, in the Golan, in Sinai”, teaching them that “we cannot rely on the Arab League states, nor on the United Nations … The only way that we have is to take up arms and fight the occupation forces.”

What is often unspoken is that Nasrallah’s ideological and much reiterated attachment to “resistance” requires conflict with Israel – or the threat of it – to give it meaning and to justify Hezbollah’s existence and the power it has accumulated in Lebanon. Conventional wisdom has suggested that Nasrallah would be constrained by Lebanon’s dire economic circumstances to resist behaviour that could invite full-scale war and undermine its own support. But in recent months Hezbollah – like Israel – has shifted its understanding of where that threshold is.

In an essay for the Atlantic Council earlier this month, David Daoud and Ahmad Sharawi described the dynamic. “The group believes this threshold is not fixed. Instead, it rises as Israeli operations in Gaza deepen, which prompts Hezbollah to act while Israel’s attention and resources are concentrated elsewhere,” they wrote. “But when these Israeli operations create growing US dissatisfaction which uniquely restrains Israel … Hezbollah feels it has more freedom of action, and thus increases the depth and lethality of its attacks.”

All of which suggests that space on either side to reverse out of the crisis is diminishing.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News