A history of hunger strikes: From the suffragettes to Guantánamo

When Falklands veteran Gus Hales wanted to complain about the way he felt he had been treated by a charity dealing with soldiers suffering from PTSD, he employed a weapon that has been a staple of the arsenal of protest for almost 150 years: the hunger strike. Mr Hales, 62, of Brecon, Powys, conducted his protest outside the headquarters of the Combat Stress charity, which he says improperly discharged him from its care in 2015. He conducted a two-week hunger strike in the run-up to Remembrance Sunday, later vowing to continue but then forced to stop due to health issues.

But while his actions might not have resulted in the satisfactory outcome he was looking for, it did achieve one of his aims – getting publicity for his cause. Which, ever since hunger strikes became a widespread method of civil disobedience, has been the aim and usual result of such protests.

Before looking at the history of hunger strikes... what exactly are they? Obviously, it’s the refusal of food, but what happens to your body if you starve yourself?

According to guidelines published by the California Department of Rehabilitations and Corrections, which advises staff on how to deal with hunger strikers, someone refusing food will initially feel hunger pangs, but these will disappear after about the third day. Glucose levels will start to fall dramatically. Between days four-to-13, the body will start to break down fatty acids as an energy source, and fatty tissue and muscle will start to be lost.

After the two week point to around 34 days, the striker will feel faint, suffer lightheadedness and dizzy spells, will feel weak and often cold, and suffer “mental sluggishness”. Days 35-42 are, say the guidelines, “considered the most unpleasant phase by those who have survived prolonged fasting” and can bring vertigo, vomiting and a difficulty in drinking water.

After seven weeks without food, you can expect confusion, loss of hearing and/or eyesight, and internal haemorrhaging. And beyond 45 days? Expect death at any point.

So why do it? Historically, the hunger strike was used by those who didn’t have any other form of protest available to them – usually, prisoners. According to medical journal The Lancet, which discussed the idea of hunger strikes back in 2008 as the government was bringing in new guidelines to help the prison service deal with them, “food refusal used as a form of protest against prison conditions, to access justice, or to make political demands may be a prisoner's only weapon. Usually, hunger strikers do not aim to die, but some are prepared to do so if their demands are not met, putting doctors in a difficult position faced with preventable death.”

The first major hunger strike to be used in this way is generally thought to date back to the 1880s, when Russian political prisoners refused food to protest against the inhumane conditions they were kept in at their Siberian gulag. But the prisoners there were not aiming for – nor would they have got – publicity for their cause. They were appealing directly to their jailers for more sympathetic treatment.

The idea of hunger strikes as a political weapon really takes hold in the early years of the 20th century when the Suffragettes employed food refusal as a means of protest – and it worked. Dr Ian Miller is a lecturer in history at Ulster University and has written widely about hunger strikes, drawing a direct line between the Suffragettes and perhaps the most famous hunger strikes of more contemporary times – the Republican prisoners held in the notorious Maze prison in Northern Ireland in 1981.

Dr Miller says: “Hunger strikes were very prominent around the time of the Suffragette movement, from around 1909 to 1914, but when I was researching a book on the subject I found that in the wake of that a lot more groups started to use hunger strikes. There were a lot of First World War conscientious objectors who went on hunger strike and got a lot of publicity, then there were thousands who did it in the Irish War of Independence from 1919 to 1921.

After seven weeks without food, you can expect confusion, loss of hearing and/or eyesight, and internal haemorrhaging. And beyond 45 days? Expect death at any point

“I searched through convict prisoner records throughout the 1930s to 1950s and found many, many more instances of hunger strikes. Even today, there are about 20 or 30 convicts a year who go on hunger strikes which never get reported in the news, but in the National Archives there’s a register of every one of them.

“Then we had the Cold War peace protesters in the 1970s, and of course there are many instances of IRA prisoners going on hunger strikes.”

The first reported incident of hunger striking during the Suffragette fight for women’s rights is that of Scottish woman Marion Wallace Dunlop, who moved to London to study art. She was arrested twice in 1908, once for “obstruction” and once for leading a women’s march. Her third arrest in July 1909, for stencilling a paragraph from the Bill of Rights on the wall of the House of Commons, earned her a spell in prison, and while in Holloway she immediately began her hunger strike, which saw her released after 91 hours due to her deteriorating health. And as a direct result of this new and worrisome (for the authorities) form of protest, the government in September that year began the policy of force-feeding hunger strikers, as Wallace Dunlop’s stand had inspired her Suffragette sisters to adopt the protest in a more widespread fashion.

Dr Miller says: “The Suffragettes claimed when Marion Wallace Dunlop went on hunger strike she was the first one to do it, that she just came up with the idea on the spot. I imagine it’s possible that she and the Suffragettes were at least aware of the Russian hunger strikes of the 19th century and saw the potential of not eating to both disrupt the prison system, cause trouble, and get publicity.”

What makes the hunger strike a highly effective tool is really based on the assumption that although it is basically an extreme method of self harm, protests utilising the hunger strike take place in a civilised, responsible society that will not just allow people to die.

“There is an expectation in an institution such as a prison that they won’t just let people die,” says Dr Miller. “But there’s also another aspect to it – the fear that if you do allow a hunger striker to die, then you are creating a martyr for that cause.

“After Bobby Sands, who led the Maze prison hunger strike, died, IRA membership went up, and there was a lot more sympathy to the IRA.

“The government back in 1909 was worried that if they let a Suffragette die then their cause would get more attention and sympathy, and ultimately undermine the government.”

Bobby Sands was a member of the Provincial IRA who was serving a sentence in the Maze for firearms possession. In 1976 the government removed Special Category Status for jailed IRA members. This meant that up to then they had essentially been treated as political prisoners; after removal of the status they were simply dealt with on the same basis as those convicted of criminal offences.

Over the next few years a series of protests were held, which escalated to the first hunger strike in 1980, culminating in what appeared to be capitulation to the prisoners’ demands in December of that year. But a second hunger strike, led by Sands, began a few weeks later when it became apparent this was not the case.

Sands died in May 1981, on the 66th day of his hunger strike, and his death prompted widespread rioting and a surge in applications to join the IRA. Then British prime minister Margaret Thatcher claimed victory, but the subsequent months were among the bloodiest of the Northern Ireland Troubles. The IRA had its martyr, through a hunger strike.

Ireland’s history is particularly allied with the concept of hunger striking. Perhaps the most prominent figure is Thomas Ashe, the leader of the Easter Rising, who died while on hunger strike in September 1917.

Dr Miller says: “I think a lot of people in Ireland present the concept of the hunger strike as a very ancient tradition stretching back to the olden days, but I don’t really follow that line to be honest. The modern hunger strike can only take place in a prison so it's only when the prison system comes along in the 19th century that you can really have a hunger strike.”

Thomas Ashe’s death brought the idea of force-feeding into sharp focus, especially in Ireland. The government brought it in in the wake of Wallace Dunlop’s death in 1909, but it was force-feeding that killed Ashe, rather than self-starvation. On his last day he was carried away by prison guards at Dublin’s Mountjoy Prison; when he was brought back to his prison hospital bed he was unconscious and had been badly beaten. The jury at his inquest noted the “inhuman and dangerous operation performed on the prisoner, and other acts of unfeeling and barbaric conduct”.

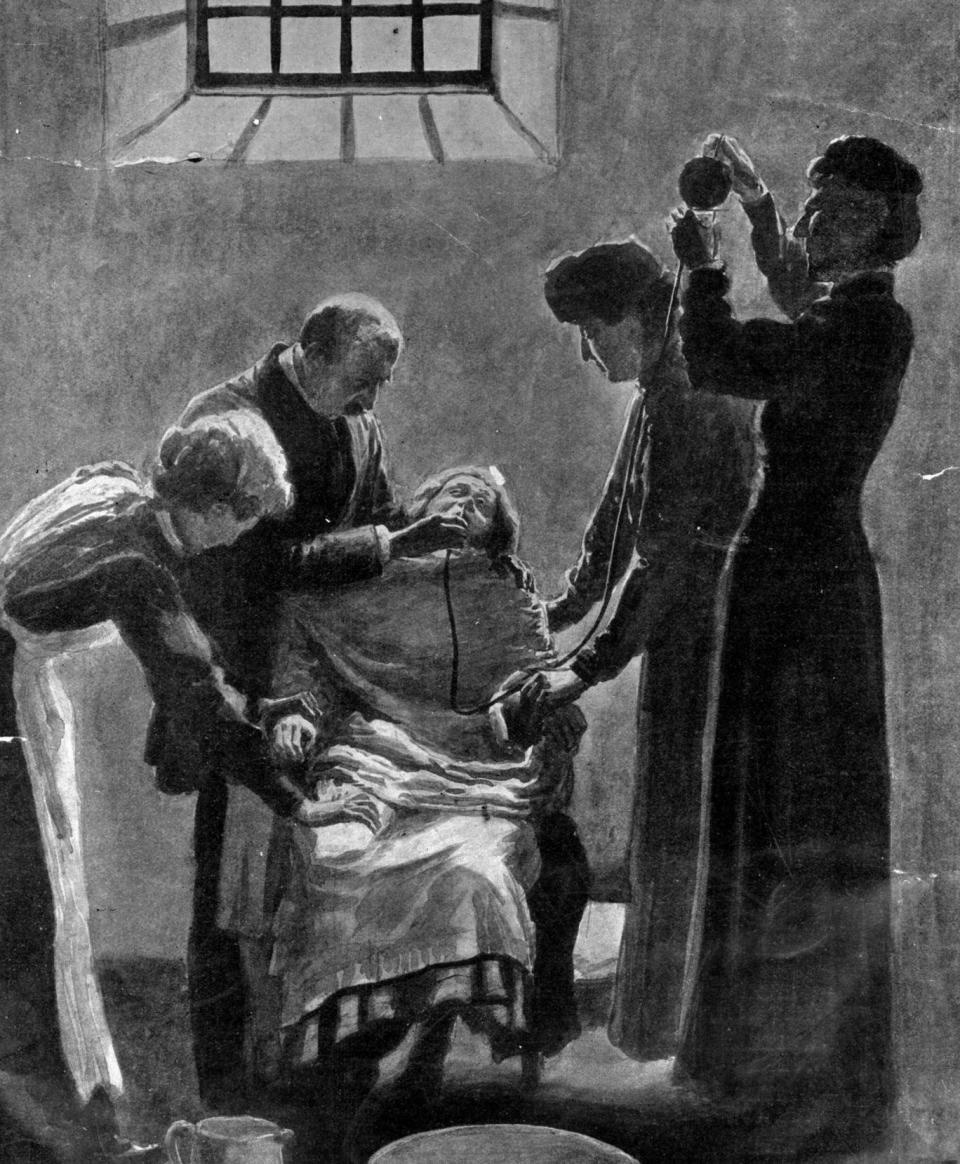

Force feeding was usually done with tubes. Sometimes, they were directly inserted nasally, but a more common way was a tube down the throat to the stomach, with milk and eggs poured into a funnel in the mouth. From the 1970s onwards, says Dr Miller, prisoners were also force-fed with Complan, a nutritional supplement more commonly used by dieters.

Hunger strikers struggled and fought against the force feeding, and their jailers fought back, holding them down and, as is evident in the case of Ashe, delivering a beating to keep them compliant

Hunger strikers struggled and fought against the force feeding, and their jailers fought back, holding them down and, as is evident in the case of Ashe, delivering a beating to keep them compliant. In the wake of Ashe’s death, the practice of force-feeding was discontinued.

“Not all hunger strikers resist feeding,” says Dr Miller. “Many of the conscientious objectors in the First World War and Cold War protesters didn’t fight back, because they were basically pacifists and didn’t want to cause violence to the doctors administering the feedings.”

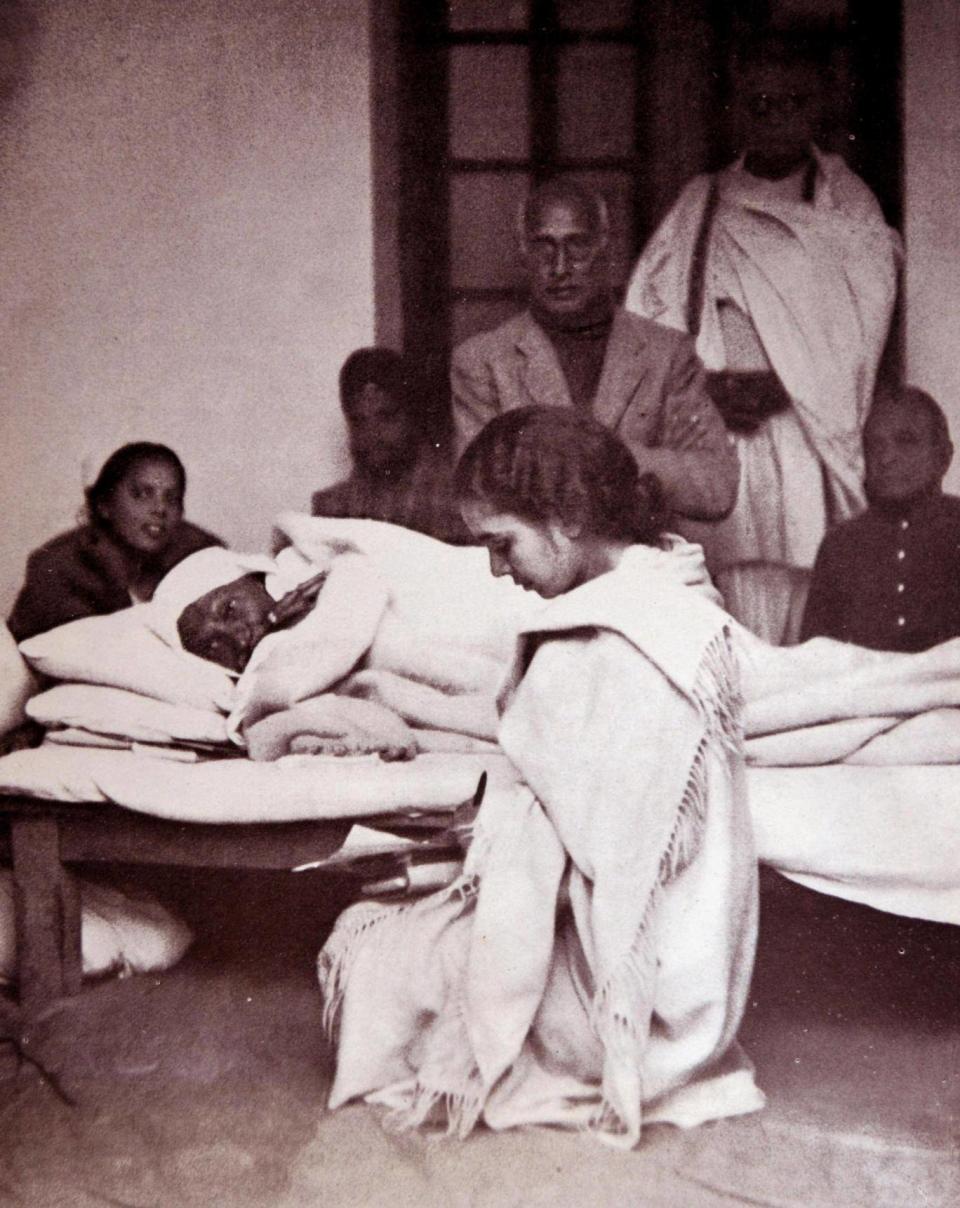

Across the other side of the world, in India, the growing Indian nationalist movement was also utilising the idea of hunger strikes, this time as a form of decidedly non-violent direct action. It was in 1918 that Mahatma Gandhi undertook a fast in support of striking mill workers in Ahmedabad. Over the course of the Indian freedom movement Gandhi would undertake 17 fasts, the longest being a 21-day hunger strike in 1943 in protest against his detention without any charge by the British authorities.

With hunger strikes being such a widespread tool in the 20th century, can we draw any connections between the various instances? Dr Miller thinks we can.

“I think after the war of independence in Ireland the Indian movement sprang up and started to utilise fasting and hunger strikes,” he says. “You can sort of see how networks of people and causes were inspired by one another… the Russian prisoners inspired the Suffragettes, and because what the Suffragettes did got so much attention and news coverage that inspired the Irish republicans, because they could see how newsworthy hunger strikes were.

“Then there were the Cold War protesters, and into the 1980s you had hunger strikes in Israel and South Africa, and of course we get to Guantanamo Bay.”

The US Naval base at Guantanamo Bay in Cuba became as notorious in the early years of the 2000s as the Maze prison was two decades before. The detention centre for those arrested – generally without charge or conviction – on suspicion of terrorist activities in the years after the 9/11 attacks, saw widespread hunger strikes in 2005.

It’s understood that hunger strikes in protest of indefinite detention began as soon as the prison opened in 2002, and continued long after. The last reported one was in 2013, after which the US military announced it would not release any further information about hunger strikes, as disseminating the information “served no operational purpose”. Perhaps they continue still, but without the oxygen of publicity that drove the Suffragette and Irish Republican campaigns, they are ultimately about as effective as the Russian dissidents in the Siberian gulags of the 1870s.

And it is full circle to Russia where the latest high-profile hunger strike story takes us. Oleg Sentsov is a Ukrainian film-maker, arrested in 2014 and sentenced to 20 years in prison on charges of plotting terrorism, widely believed to be fabricated. In May this year, Sentsov embarked on a hunger strike in protest, protesting not just his own situation but the fate of all Ukrainian political prisoners detained in Russia.

Sentsov’s 100-day hunger strike succeeded in getting his voice heard; the artistic and film-making community have been putting pressure on President Vladimir Putin to release him, and just this week the legendary French director Jean-Luc Godard snubbed an invite to a St Petersburg museum, directly citing Sentsov’s incarceration as his reason. According to French news outlet Le Figaro, Godard replied: “Thank you for your invitation, but given the condition of Sentsov’s detention, I do not feel that I can visit the Hermitage (Museum of St. Petersburg) for the moment, regardless of my friendship for the people.”

Dr Ian Miller is a historian, not a futurist, but asked to look forward and consider whether hunger strike as a form of protest will endure, he says: “I don’t think it will go away to be honest. People know that it annoys the government, for a start.”

Indeed, hunger strikes abound. In Syria, reports Al Jazeera, dozens of inmates of the Hama jail are on indefinite self-starvation in protest against death sentences handed out to 11 people for their part in protests against the government in 2011. In August, human rights lawyer Nasrin Sotoudeh, who represents women’s rights activists complaining of the compulsory veiling of women in Iran, began a hunger strike in protest against harassment of her friends and clients. She has been in Evin Prison since June after her arrest. This month, Khader Adnan of the West Bank city of Jenin was released from detention by Israeli forces after completing a 58-day hunger strike in protest against his arrest.

And Gus Hales, Falklands veteran, decided to draw attention to the plight of himself and other military personnel suffering from the effects of war in the only way he knew how: by refusing food.

Hunger strikes capture the public imagination, which is why they are such an effective form of protest, especially for those who have no other means of fighting because they are incarcerated or disenfranchised. It’s a bleak and brave thing to put your very life on the line for what you believe in, especially when the situation seems hopeless. But as the American lawyer Clarence Darrow said, “lost causes are the only ones worth fighting for”.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News