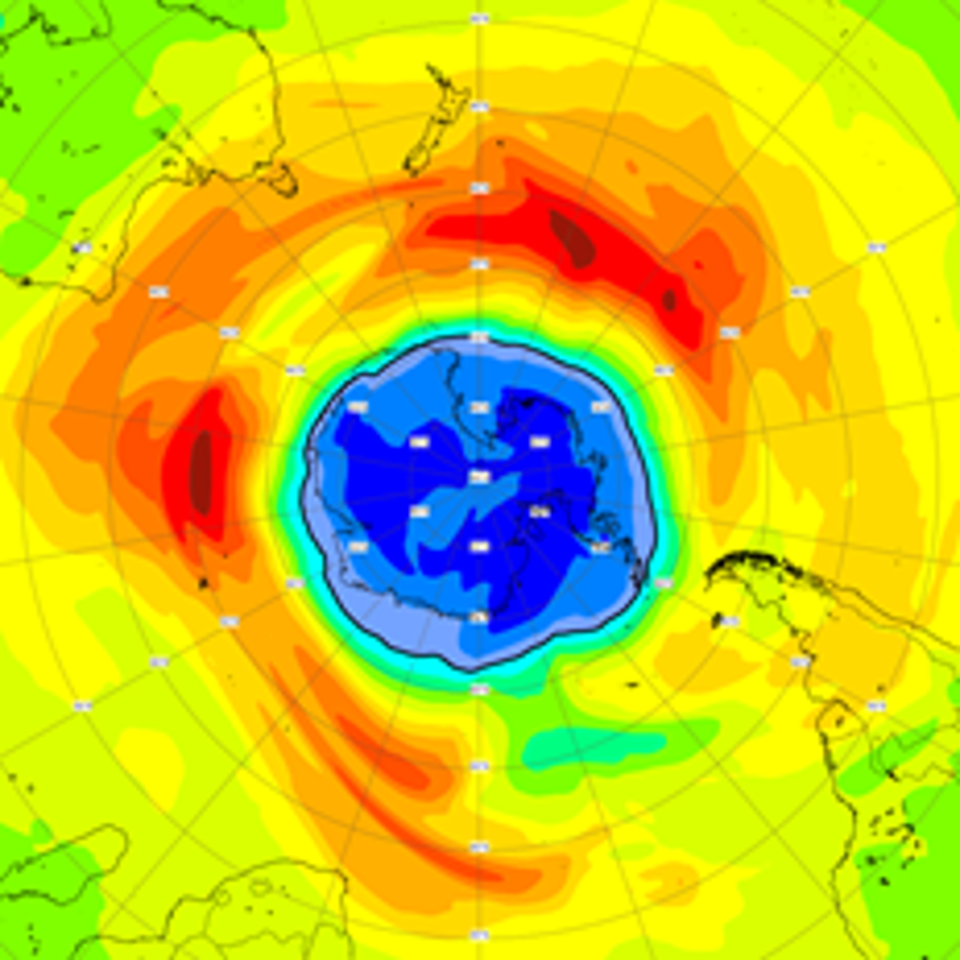

Hole in the ozone layer over South Pole is now greater than size of Antarctica

The hole in the ozone layer over the South Pole is now larger than the size of Antarctica, according to forecasters.

Scientists reported on Thursday that after a “pretty standard” start to 2021, the ozone hole became notably bigger this past week. It is now larger than 75 per cent of ozone holes at this stage in the season since 1979.

The ozone layer is the thin part of the atmosphere which shields life on Earth from harmful ultraviolet radiation. In humans this can cause health issues like skin cancer and eye damage while also impairing plants’ ability to absorb carbon, an important part of mitigating the climate crisis.

A stratospheric hole appears annually during the Southern Hemisphere’s spring from August to October. (A hole can sometimes also appear over the Arctic region between March and May.)

The 2021 hole appeared to surprise forecasters from the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (CAMS), part of the EU-funded, Earth observation programme.

“This year, the ozone hole developed as expected at the start of the season. It seems pretty similar to last year’s, which also wasn’t really exceptional in September, but then turned into one of the longest-lasting ozone holes in our data record later in the season,” CAMS Director Vincent-Henri Peuch said in a statement.

“Now our forecasts show that this year’s hole has evolved into a rather larger than usual one. The vortex is quite stable and the stratospheric temperatures are even lower than last year. We are looking at a quite big and potentially also deep ozone hole.”

Complex meteorological and chemical processes are behind annual ozone hole formation. CAMs reports that in the South Pole, temperatures high up in the stratosphere begin rising around October, which slows ozone depletion. By the end of the year, levels are typically returned to normal.

In the mid-1970s, it was discovered that ozone layer thinning was being dramatically worse by human use of halocarbons – chemical substances found in products like refrigerators, packaging and aerosols.

All 198 member state of the United Nations signed the Montreal Protocol of 1987 to ban the chemicals.

Research last month suggested just how critical that international agreement was: the continued use of halocarbons would have added 2.5C to average global air temperatures by 2100. And that’s on top of additional heating from other greenhouse gas emissions.

“We would be facing the reality of a ‘scorched Earth’” scenario, researchers wrote.

Dr Paul Young, from Lancaster University and the study’s lead author, told The Independent that “it would likely have been pretty catastrophic”.

16 September is designated as the International Day for the Preservation of the Ozone Layer, to mark that turning point.

Since halocarbons were banned, it has been in a slow recovery. Scientists say it will take up to the 2070s to see a complete phasing out of ozone-depleting substances.

Read More

Gorilla mothers carry their dead babies around, suggesting they grieve

Australian wildfires caused twice as much CO2 as previously estimated

Dozens of climate activists arrested in new M25 protest

Why is the M25 closed? Motorway protests explained

The Central European countries putting the EU’s climate strategy at risk

Yahoo News

Yahoo News