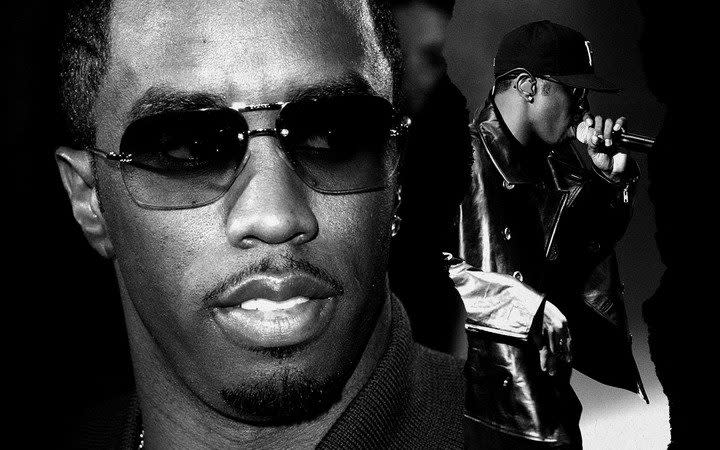

‘This could trigger hip hop’s MeToo’: How Sean ‘Diddy’ Combs may fall from grace

It was supposed to be the start of another new chapter in the rich and varied career of Sean Combs. The man who was Puffy, then Puff Daddy, then P Diddy, then Diddy, then Swag, then Puff Daddy again, and most recently Love, visited Britain last autumn to promote his first solo album for 17 years, The Love Album: Off the Grid.

Combs was enjoying being appreciated, as he so often does. Two months earlier the producer, label executive, occasional rapper and business mogul had appeared at the MTV Video Music Awards in New Jersey, where he was feted with the Global Icon Award for his seismic contribution to music since the mid-1990s, and ran through a medley of hits, including I’ll Be Missing You and Bad Boys For Life.

During a whistle-stop promotional visit to the UK, he made a headline appearance on The Graham Norton Show (“I hope you’re in the mood for Love tonight because Sean ‘Diddy’ Combs is in the house!” Norton trilled, introducing an often incoherent and, sorry, noticeably puffier Combs than many remembered), performed with the south London rapper Giggs, and threw a star-studded 54th birthday party for himself at a luxury hotel in Marylebone, where Naomi Campbell and Idris Elba were among well-wishers.

On the same day, he received his 14th Grammy nomination, and first for two decades. “Extremely humble, grateful and blessed,” he said in an Instagram video taken outside the hotel’s lobby. Whatever name he was going by, Combs was back, it seemed. “Thank you, thank you, thank you,” he rambled. And it really was to be the start of a new chapter – only not the kind he planned.

One week after Combs’s visit to London, he was sued for sexual assault by Casandra Ventura, his former girlfriend, who was once signed to his label, Bad Boy, as the singer Cassie. In a lawsuit, Ventura claimed she was trapped in a cycle of abuse and violence by Combs. She alleged he raped and beat her over 10 years, plied her with drugs and alcohol, and forced her to engage in sexual activity with male prostitutes over a period of years and in numerous cities – meaning she was a victim of sex trafficking.

They settled the legal case one day later. No details were given, but Combs’s lawyer reiterated his denial of all allegations: “Just so we’re clear, a decision to settle a lawsuit, especially in 2023, is in no way an admission of wrongdoing.” Yet three more lawsuits alleging similar misconduct followed – allegations that, again, Combs and his lawyer have strongly denied and described as “sickening” and “complete lies” that would be addressed in court.

Throughout all this, as social media fired up the rumour mill, Combs’s once bulletproof reputation fell apart, and commercial partners started to desert him. Then he largely went to ground. He wasn’t present to see himself fail to win the Grammy last month. And if he thought the matter might fade from public consciousness merely with his absence, well, he was wrong.

On Monday, Combs’s properties in Los Angeles and Miami were raided by officials from US Homeland Security in connection with a “federal sex trafficking investigation”, according to the US network Fox 11. The following day, Combs’s lawyer complained about a “gross overuse of military-level force” in the raids, which saw two of the music producer’s sons handcuffed, and stated the investigation was “nothing more than a witch hunt based on meritless accusations made in civil lawsuits”. Combs, who was photographed in Miami earlier in the week, has not been arrested nor had his travel restricted.

Still, the drama and scale of the simultaneous raids was unmissable. Suddenly, mainstream news and entertainment channels – the outlets he has mastered and manipulated for decades – were full of stories again about the potential downfall of a once untouchable mogul. “Mo’ money, mo’ problems,” so the song he produced and featured on went, 27 years ago. As he climbed towards billionaire status, that prophecy didn’t seem to apply to Combs himself. Now it does.

Combs was born in Harlem, New York City, and raised in the suburbs. Combs’s mother, Janice, was a model and teaching assistant, while his father, Melvin, was “a drug dealer and a hustler” who was shot dead when he was three years old. “I have his hustler’s mentality, his hustler’s spirit,” Combs has said.

Nicknamed “Puff” as he would huff and puff when he was angry, the young Combs was an operator: at Howard University he promoted parties, then left after a few terms to join Uptown Records as an intern, before forming his own label, Bad Boy Records, in 1993.

Nobody – perhaps not even Combs – would say that he has ever been possessed of remarkable talents as a musician. His rapping is weak (it is well understood that his lyrics are ghostwritten), his dancing limited, and despite being a legendary hip hop producer, he doesn’t make beats.

Yet he knew what sounded good, what looked good, and – crucially – what would sell. In common with Michael Jackson, Combs is obsessed with P.T. Barnum (“my muse,” he called him last year), the great American showman who didn’t care what he put on stage so long as it was entertaining.

“Diddy is more of a conductor of people: he’s always been very good at telling other people what to do and helping other artists become big. But his biggest critics have always claimed he takes too much credit for beats or rhymes created for him by other people,” says Thomas Hobbs, a music writer and rap critic. Through Bad Boy, Combs signed numerous artists who became some of the biggest names in hip hop.

“Whether you see him as a producer, rapper or cold businessman, you cannot deny his influence. Without him we wouldn’t have Usher, Mary J Blige, Biggie Smalls – so many pivotal, paradigm-shifting artists he helped fast track into pop stars. It’s why his stranglehold on the industry has always been so big.”

And it was. That rap is now the dominant force in pop culture today, forming the bedrock of the charts, influencing fashion and sports, and being the lingua franca of teenagers everywhere, has as much to do with Combs as almost any individual. Through Bad Boy, he drove a commercialisation of hip hop, broadening its appeal with music videos featuring parties filled with bikini-clad women coated in oil, men in furs and top hats, wads of cash flung with abandon, expensive bottles in nightclubs and brand names dropped like yo-yos.

At the same time as rap went mainstream, Combs was also involved in the most notorious feud in music. He was the posterboy for East Coast rap; on the West Coast, the scene was led by Suge Knight’s Death Row Records. When either side’s star artists were shot dead – Death Row’s Tupac Shakur in September 1996 and Biggie Smalls, aka the Notorious B.I.G., in March 1997 – many speculated that the rivalry could have been behind the killings. Both sides have denied that theory, with Knight dismissing it as “something that’s trumpeted by the press.”

Yet, despite no connection ever having been established, Combs has never been able to shake off entirely unsubstantiated gossip suggesting he might have been linked to Shakur’s death in some unspecified way. (Incidentally, he turned his grief for Smalls into his biggest hit, The Police-sampling ‘I’ll Be Missing You’.)

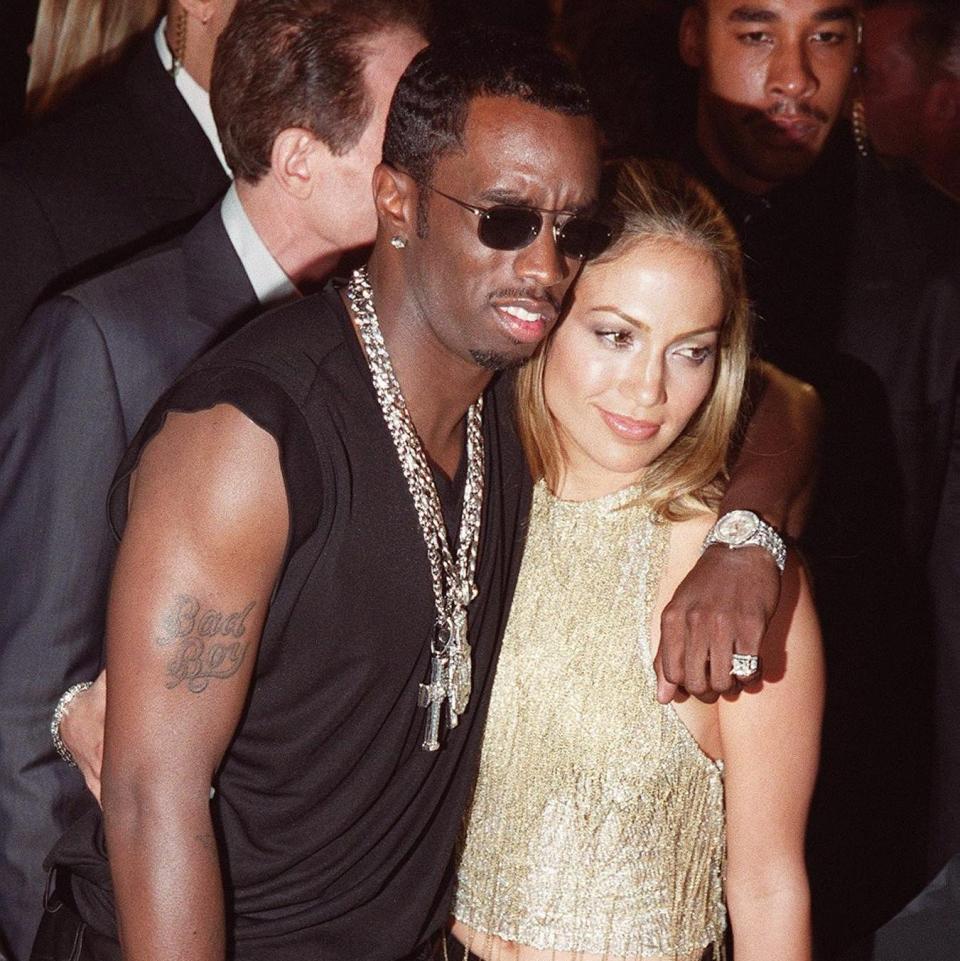

“There’s always been this PR-spin that he’s this lovable entrepreneur, with catchy songs and catchphrases. In reality, when you look into him, trouble attaches itself to Diddy like a magnet, and for all the positives, there’s never a negative story too far behind,” Hobbs says. On one occasion, in 1999, Combs, who was with his then-girlfriend Jennifer Lopez, and his protégé Shyne were arrested for weapons violations after a dispute in a nightclub. After a highly publicised trial, Combs was found not guilty on all charges, while Shyne was convicted on five of his eight charges and sentenced to 10 years in prison. “From his artists fighting to get their publishing back to the infamous East versus West beef, we’ve heard Diddy linked to problematic things for years,” Hobbs says.

His outlandish personality and preternatural ability to make money from doing the bare minimum in a song made him easily parodied. In 2000, the reality TV series Making the Band saw him test some would-be stars. In one episode, he requested the band members get him a piece of cheesecake. They were not permitted to take a car, or taxi, or any public transport, and had to walk more than five miles in the dead of night to get him the dessert.

“It’s not about me trying to do a mean-spirited initiation hazing act. There’s a bigger picture to it. In the world of music, I have to get up every day and do a bunch of s–t I don’t wanna do,” Combs said, attempting to justify the challenge. But he also did a bunch of stuff he definitely did want to do, including throwing notoriously wild parties that, by all accounts, weren’t entirely different from the misogynistic videos MTV lapped up.

For a time, he clearly enjoyed being the omnipotent Svengali figure of urban music: a gatekeeper who could make or break careers, and whose pupils tended to learn the ways of the world quickly. Usher, who is only nine years Combs’s junior, was sent to live with Combs in New York when he was only 13. In a 2004 interview with Rolling Stone, Usher revealed how Combs introduced him to “a totally different set of s–t – sex, specifically”.

Usher went on to recall how “there [were] always girls around. You’d open a door and see somebody doing it, or several people in a room having an orgy. You never knew what was going to happen.” Years later, in 2009, Combs spent time mentoring a 15-year-old Justin Bieber too, including appearing to promise him a car and house. Combs was 39 at the time. A video thought to be from the Noughties, featuring the pair, has been shared widely this week.

Last December, an anonymous woman accused Combs and two other men of raping her in a New York recording studio when she was 17. “Sickening allegations have been made against me by individuals looking for a quick payday. Let me be absolutely clear: I did not do any of the awful things being alleged,” Combs said after the filing of that lawsuit.

In another lawsuit, the record producer Rodney Jones has accused him of a litany of sexual assault allegations. “Mr. Combs was known for throwing the ‘best’ parties,” the lawsuit reads

Meanwhile, Combs’s lawyer has said: “We have overwhelming, indisputable proof that [Jones’s] claims are complete lies. We will address these outlandish allegations in court and take all appropriate action against those who make them.”

In the 2000s, Combs collected celebrity friends like stamps, forging wider connections by adding acting in films and a Broadway play to his CV, plus political activism, various businesses – his company, Combs Global, includes his record label, a bottled water brand, and his Sean John clothing line, among others – and philanthropic endeavours.

He met with Barack Obama as early as 2004, and was given a tour of the White House by George W Bush. Oprah interviewed him about his struggles in life. His 50th birthday party was attended by most of the A-list. He has met Princes William and Harry just once, at a charity event in 2007. But he expressed a desire to get to know the latter more: “He’s such a cool guy and it’s about time we hung out. I need him to take me to some of those wild Mayfair clubs.”

The question is now being asked about whether Combs’s lawsuits could initiate a reckoning against powerful men in the music industry. So far, there have only been isolated and very high profile cases such as R Kelly, who was sentenced in 2022 to 30 years in prison for sex trafficking and racketeering. Dream Hampton, the activist whose series Surviving R Kelly played a central role in bringing him to justice, claimed to The New York Times that “Puff is done”.

“Hip hop hasn’t really had its MeToo moment, and should these claims be proven in court, it feels like this could be a trigger for that. It speaks to a wider culture of moguls that felt they were untouchable, throwing parties filled with women, and thinking that was part of the lifestyle. So is this just the tip of the iceberg? Diddy is connected to so many hip hop legends,” Hobbs says. “You wonder how many people gave him a pass or enabled toxic behaviours.”

In public, Combs has always made sure people see him as a rags-to-riches bon vivant, a gentle father of seven children who just wants everybody to kick back and have a good time. But, after 30 years of keeping it up, the party may now be over for Combs. Whether he likes it or not.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News