'We know we're more than a TV show': how Sesame Street made it to 50

On a fall day, 50 years ago, PBS began airing Sesame Street, a show inspired by a question: what if the visual flash and frenetic pace of TV were used to teach kids about letters and numbers instead of about breakfast cereals?

Within a year of its 10 November 1969 debut, Sesame Street was a sensation. Children loved it. Hard-working parents were grateful for it. Critics and academics alike couldn’t stop talking about it – both positively and negatively. Some pundits wondered if a popular series geared toward short attention spans would result in a generation that never learned to focus. Others were suspicious of the show’s secondary mission, to make an educational program that reflected the lives of its audience … from their unspoken anxieties to the color of their skin.

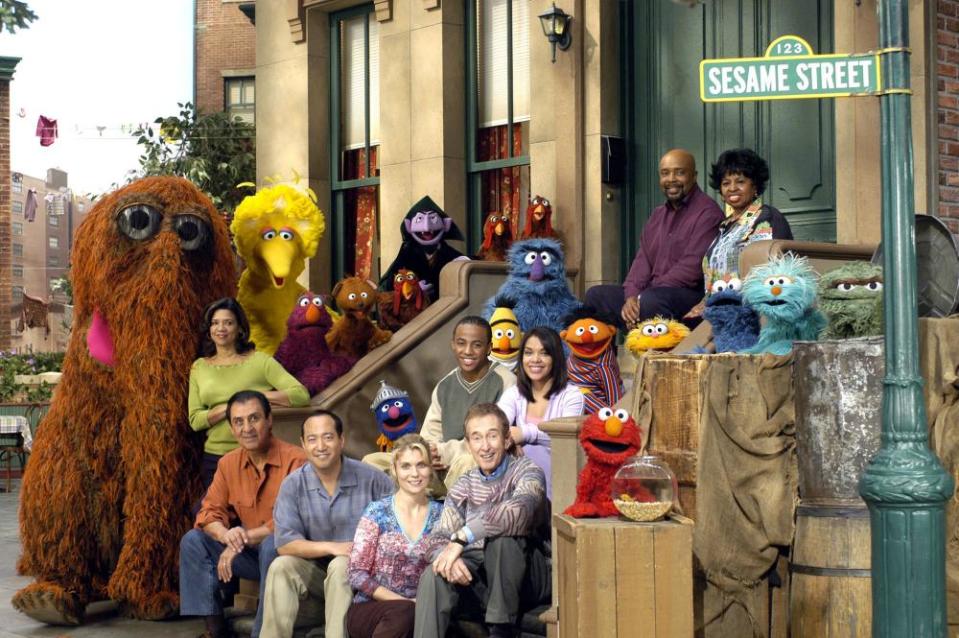

Decades later, a lot has changed about Sesame Street and while some still question its methods and message, millions of new parents eagerly introduce their toddlers to Big Bird and Elmo every year.

Sesame Street’s current executive producer, Ben Lehmann, was two years old when the show originally premiered. He joined the crew as a production assistant in 2001, and appreciated the rewards of making TV that has “a greater benefit than just entertainment”. He laughs that the running joke around the Sesame Workshop is that every new season since the first one has been “experimental”. Every year, he says, “We look at the research, we bring in development experts and we look at the needs of kids presently. We’re always reinventing ourselves.”

Related: Sesame Street takes on opioids crisis as muppet's mother battles addiction

Sesame Street was the brainchild of Lloyd Morrisett and Joan Ganz Cooney, the latter of whom – according to Lehmann – was watching kids sing along to TV beer commercial jingles when she asked herself: “Can we use television to teach something important?” The earliest episodes were an explosion of abstract animation, catchy pop music and documentary footage of kids at play and grownups at work, all delivered in short, colorful bursts. The show looked like someone had randomly cut together outtakes from an underground film festival.

Eventually, the children who absorbed the Sesame Street style as preschoolers would go on to make MTV, Nickelodeon cartoons and viral videos. Media scholar Myles McNutt, an assistant professor in the communication and theatre arts department at Old Dominion University, says: “It’s hard now to think that Sesame Street was ever radical, because so much of TV looks like that. But what Sesame Street was doing was thinking about how best to reach its audience, in ways the rest of TV at the time was slower to account for.”

But it’s not just a snappy style that explains why Sesame Street has been on the air for 50 years. Laugh-In was the hippest show on the air in 1969, and it petered out by 1973.

Most children’s shows before the 1970s were shot in plain-looking studios, and hosted by cartoonish older white men and women, sporting silly costumes. Sesame Street’s human characters were multi-ethnic and looked and talked like ordinary people, performing normal jobs. From its early years to now, the show has taken its cues from one of its most memorable songs: Who Are the People in Your Neighborhood? It’s moved beyond math and reading to teach kids about, well, life. Simple human dignity, what people do all day and why. These are useful things for anyone to understand, at any age.

And for comic relief? Sesame Street always had Jim Henson’s magnificent Muppets. Pre-Sesame, Henson and his team had been working in television for over a decade, delivering whimsical humor to commercials and variety shows. Their first wave of Muppet characters on Sesame Street – Grover, Oscar the Grouch, Bert and Ernie and the like – were good teachers. But they were even better at getting laughs, with their spindly-limbed slapstick and funny voices.

In the Sesame Street 50th anniversary special that recently aired on HBO (which will rerun on PBS on 17 November), a parade of the show’s more obscure Muppets zips by, along with some of the humans and cartoon characters who have been part of the show’s more enduring comic bits. Remember the baker with an unwieldy pile of cakes? Remember the little girl reciting her grocery list? Remember Guy Smiley?

“We know we’re more than a TV show,” Lehmann says. “We’re always looking back at classic segments and trying to stay true to Sesame Street as a community, as a thing that’s beloved by a lot of people.”

That said, Sesame Street has been known to disappoint its older fans. Some adults who watched in the 70s and 80s have expressed dismay at the rise of Elmo, a furry red Muppet with a childlike demeanor, whose massive popularity has led to more “little kid” Muppet characters, such as Baby Bear and Abby Cadabby. The format of the newer episodes is different too, with more emphasis on story-driven segments that can run as long as 10 minutes. Lehmann explains: “We now know what we didn’t know 50 years ago, which is that kids actually love longer narratives.”

Some of the more jarring changes in Sesame Street over the years have been prompted by concern from pediatricians and child psychologists. It was doctors who reportedly convinced the producers to make Big Bird’s friend Mr Snuffleupagus start appearing to the grownup characters, so that kids watching at home would know they could trust adults to believe them. And it was doctors who got Cookie Monster to eat the occasional vegetable.

Some changes have been well-received, including the recent additions of an autistic Muppet character, Julia, and a Muppet in foster care, Karli. There will always be parents who will complain that Sesame Street pushes a progressive agenda with its emphasis on diversity, but as Lehmann notes: “There’s a lot of kids who are in foster care, and there’s not a lot of content out there speaking to them. Diversity and inclusion have been part of our mission from the very beginning.”

Perhaps the most controversial Sesame Street issue lately has been the Workshop’s deal with HBO, which gives premium cable subscribers early access to new episodes before PBS viewers. When this plan was first announced, it struck some as contrary to the show’s original goal of delivering quality programming to all kids, regardless of economic means. But as McNutt suggests: “It’s a practical reality that PBS’s tenuous funding means the show depends on merchandising and licensing fees in order to keep operating. And merchandising is not what it was. The HBO deal was necessary in order to keep the show’s mission alive.”

McNutt adds: “What’s interesting to me is how that crisis revealed the ways in which Sesame Street is perceived as a public good. The show has championed the idea that it’s accessible to kids of all ages and all social and cultural backgrounds. This [outrage] really positioned Sesame Street and its educational mission as something the public had a right to.”

Lehmann points out that the public still has plenty of access to Sesame Street. The Workshop’s own numbers show that between HBO, PBS, the show’s webpage and its YouTube channel, more than 10 million kids under eight years old watch Sesame Street content each quarter.

That’s not even taking into account the grownups – some childless – who still find their way to Sesame Street videos online, watching parodies of recent popular songs, celebrity guest appearances or Kermit the Frog singing about how it’s not easy being green.

The show’s ultimate legacy may be either that it continues to move the people who watched it as kids, or that those adults are now comfortable with consuming entertainment in chunks. Either way, the show has long since grown beyond the TV-sized box that was originally meant to contain it.

As McNutt says: “The reality is that Sesame Street’s impact can no longer be measured as ‘Who is sitting in front of the TV watching? If you think of Sesame Street as a television show, that’s long been inaccurate. It’s a cultural product.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News