NHS £2.6m blood infusion transforms life for haemophilia B patients

A £2.6 million gene therapy which means haemophilia B sufferers no longer need daily treatment has been made available on the NHS.

One patient who took part in trials said he felt “cured” by the transformational one-off infusion which gave him a “new lease of life”.

The treatment, which dramatically increases levels of a key clotting agent in the patient’s blood, is one of the most expensive in the world – its official cost is £2.6 million per infusion.

However, health officials have negotiated a confidential deal with manufacturers which means the sum paid will be significantly less, while the final payments will depend on how successful the drugs prove over the next decade.

Prof Sir Stephen Powis, NHS National Medical Director, said: “This transformative gene therapy is the first of its kind for haemophilia B patients on the NHS and has the potential to significantly improve the lives of hundreds of people by helping to reduce symptoms such as painful bleeds.

“It is a one-time therapy that could be truly life-changing for some, as it could help people avoid the need for regular hospital visits.”

Prof Powis said the drug was the latest in a series of pioneering gene therapies to be secured for the NHS at an affordable price.

It is the first drug to be made available on the NHS via an “innovative medicines fund”, which gives patients early access to a treatment while further data is collected on the long-term benefits.

‘I’ll always be grateful’

Elliott Collins from Essex, is one of the first to benefit from the drugs, having taken part in trials of the gene therapy in 2019.

The 34-year-old, who has severe haemophilia B, used to have twice-weekly injections of factor IX replacement, but he has not needed any treatment since the trial.

He said: “I will always be grateful for the quality of life I’ve had for the last five years, which hopefully will continue for a good while longer. I feel in the best health of my life.”

Mr Collins agreed to take part in a gene therapy trial partly because of the devastating consequences of untreated haemophilia his family has experienced. His brother, Joshua, died as a newborn baby due to a brain bleed, and his great uncle died aged 14, also as a result of haemophilia.

Mr Collins said: “I did gene therapy partly because of the benefit I would receive, but also because my family has suffered because of a lack of treatment.

“If my brother had survived the trauma of his birth, he would hopefully have been OK, and eligible for gene therapy. I couldn’t do anything for him, but I felt this trial was something I could do to help improve treatment for the future.”

Protein deficiency

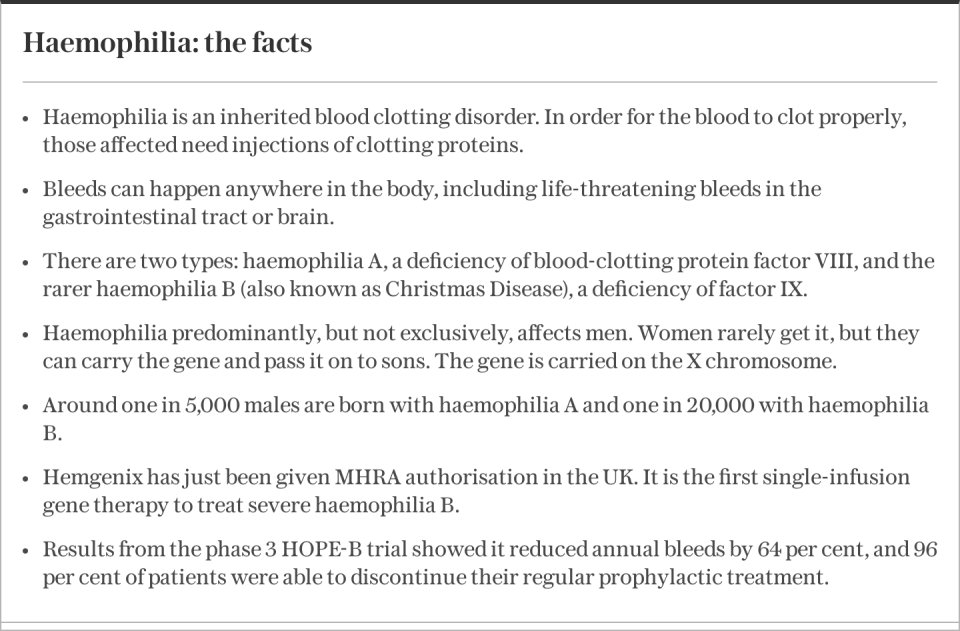

When someone without haemophilia suffers a cut, the body activates a series of proteins in the bloodstream which make the blood sticky and seal the wound with a clot.

But those with haemophilia are unable to make enough clotting factor IX. Without this crucial protein, bleeds are bigger and longer. They can also happen spontaneously inside joints, causing long-term damage.

Gene therapy works by artificially creating a working version of the factor IX gene.

During a one-off infusion, which takes about an hour, the gene is introduced into the body within a viral vector, an inactivated virus which cannot spread and does not cause illness.

The virus is used to carry the factor IX gene to the liver, after which it is broken down and removed by the body. The liver can then start making its own factor IX.

Sneaky skateboarding

Mr Collins, from Colchester, told BBC News he rebelled against his diagnosis as a child by sneakily playing rugby or skateboarding. But any injury risked a damaging bleed.

He had injections of factor IX twice a week, and more if he was injured, for 29 years. “I would have to think about it all the time,” he said.

Mr Collins said he knew the new therapy was working when he whacked his knee into a cupboard. He expected it to balloon up and require treatment, but just a small mark appeared.

Tests showed that levels of factor IX in his blood had gone from 0 to 60 per cent of normal.

Clive Smith, chairman of the Haemophilia Society, said: “The availability of gene therapy through the NHS for people living with severe haemophilia B marks a major milestone for our community.

“At its most effective, gene therapy has the potential to transform lives by eliminating painful bleeds and removing the need for regular, invasive, treatment.

“This is another important step towards our goal that everyone living with an inherited bleeding disorder has access to treatment which allows them to lead a full and independent life.”

Around 250 patients eligible

The treatment is being made available through a deal between the manufacturer, CSL Behring, NHS England and the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (Nice), the body that rules on cost-effectiveness.

There are currently about 2,000 people in the UK who live with haemophilia B. Nice estimates around 250 will be eligible for the new treatment in England, where the therapy will be open to adults with factor IX levels less than 2 per cent of normal.

Normal clotting factor injections cost between £150,000 and £200,000 per patient per year, for life. If gene therapy is successful, it should eliminate the need for day-to-day treatment for at least three years – and potentially more than a decade.

NHS providers will be commissioned to deliver treatment in each NHS England region, with centres in London, Oxford, Manchester, Leeds, Bristol, Birmingham and Cambridge.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News