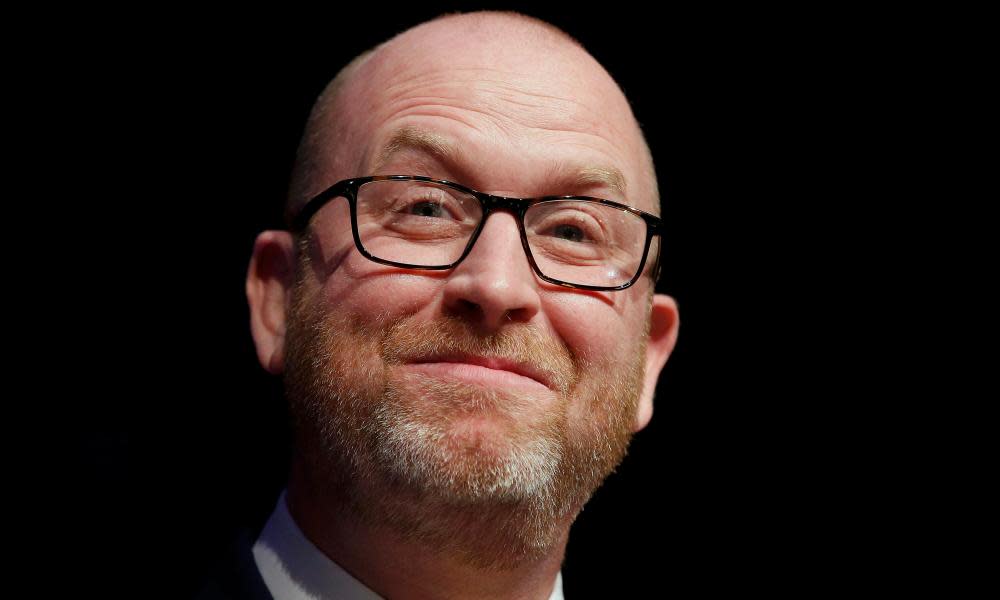

In Paul Nuttall, Ukip’s hypocrisy is finally being revealed | Zoe Williams

Double standards in the media and in parliamentary rhetoric, as they relate to political parties, are so flagrant as to be barely worth mentioning. Some parties are simply expected to be more consistent than others. Indeed, to question out loud how the Conservative party can move from the free market libertarianism of David Cameron to the bunkered protectionism of Theresa May, while the Labour party cannot be permitted a London mayor who dresses a little bit differently to its leader, would be so obvious as to sound almost boorish. So it’s easy to forget that ideological inconsistency can have a greater significance than how it initially plays to the audience.

So it is with Ukip: this party has made no rational sense since it captured the name from its anti-federalist founders and wrestled it into a one-man, anti-everything machine. It is the party that wants to protect British people’s access to their pressurised public services, while at the same time privatise the NHS; it’s on the side of the little guy and wants to fight for fair wages, at the same time as wanting to deregulate worker protection in the interests of cutting red tape. It thinks it an outrage that you can’t afford your rent, but has nothing to say on social housing, beyond that migrants shouldn’t be allowed it.

Either you’re on the side of authority, or you’re prepared to question it in the interests of justice

In the end, though, it was a rather subtle contradiction that cast it into disarray. The false claims made on Ukip leader Paul Nuttall’s website – that he lost close friends in the Hillsborough disaster – we can file under “the unfortunate consequences of having no integrity” and deal with later. The full chaos only unfolded after the party’s chief donor Arron Banks weighed in, with his scornfully bored analysis, saying he’s “sick to death” of hearing about the disaster.

Two Ukip officials – Adam Heatherington and Stuart Monkham, Merseyside and Liverpool chairmen respectively – quit over the assorted remarks last week, and in the run-up to a byelection that couldn’t be more important for the party.

It may have been subtle but it was, in the end, the greatest contradiction of all that undid Nuttall and Banks: espousing the interests of the common man, while furthering only the interests of money.

Such a tension can stand up to an extraordinary amount of scrutiny, so long as it’s all of a very superficial nature, leavened by the delightful spectacle of Nigel Farage drinking a pint. But it cannot stand up to the glare of a campaign like Hillsborough: either you’re on the side of authority, or you’re prepared to question authority in the interests of justice. You cannot be both.

Banks is a distinctly British example of what the biologist and anthropologist Peter Turchin calls “elite overproduction”. Turchin is a pioneer of cliodynamics, a discipline that examines history as a science, modelling trends mathematically according to a series of measures – inequality and population growth being the two most obvious.

As inequality grows, the total number of the wealthy increases, to the point that there are more of them than there are elite positions, the number of political offices being fixed. This has an impact on the “social mood” – hyper-individualism taking the place of collective action, both in rhetoric and in fact. But it also leads these elites to look for new ways to influence politics, as they are edged out of the positions they consider theirs by right.

This can occur subtly over time – there is solid evidence in the US that huge inflows of money to thinktanks from high-net-worth individuals such as Newton and Rochelle Becker, and Richard Mellon Scaife, completely changed the way the US mainstream perceives and discusses Islam.

Or it can manifest itself more suddenly, with wealthy donors altering the political process by simply flooding parties such as Ukip, or campaigns such as Leave, with money. Either way, politics changes, and for a reason; not because large swaths of people feel ignored, but because a handful of decamillionaires considers themselves insufficiently heeded.

While these influencers can seem almost omnipotent with the speed of their victories, there are a few political advantages money can’t buy. Movements that build organically, such as Momentum, can get their supporters out on the streets. High-spirited Labour supporters estimate they got to every single household in central Stoke at the weekend to discuss the many qualities of byelection candidate Gareth Snell.

While canvassing isn’t decisive – Labour had far more “contacts” than the Conservatives during the 2015 general election – the comparable scarcity of Ukip canvassers was matched only by their unconventional execution of the job (one canvasser was captured urinating on a voter’s fence and then trying to force his way into her home).

The bigger drawback for Ukip is the thinness of its high command: Nuttall, described by commentators on his election to the leadership as a nightmare for Labour (some combination of his professional manners and common touch), will make whatever claim comes into his head (that he has a doctorate; that he’s on a charity board) if he thinks it will strengthen his case in the moment.

Never mind the lack of probity, it is a childish carry on, doomed to be almost instantly exposed, bringing not just himself but his party and, indeed, the political process into disrepute. His Ukip colleagues must have known this about him from a long way off; it is the most obvious thing about him from the smallest trace of contact.

He has never mustered the slightest interest in accuracy at a political level, yet it is the emergence of nonsensical claims for himself – the professional football past is the most infantile, but in some oblique way the most lacking in respect – that put him in his own league.

The fact that Ukip members had no greater ambition for their party’s leadership may convey something of the post-truth landscape, a new cynicism in which those on the right will not just accept but anticipate with glee any sign that the electorate doesn’t care about honesty.

But it indicates, also, that a movement without roots is one without choices. The question is not how far Ukip can go, but how much integrity it can drag down with it as it disintegrates.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News