The racism that killed George Floyd was built in Britain

Pay attention to African Americans.

Related: The perils of being black in public: we are all Christian Cooper and George Floyd | Carolyn Finney

The headlines are now describing the US as a nation in crisis. As the protests against the killing of African American George Floyd by a white police officer enter their second week – curfews in more than 40 cities, the deployment of the national guard in 15 states – there is a far deeper, more important message. Because the US is not, if we are honest, “in crisis”. That suggests something broken, unable to function as planned. What black people are experiencing the world over is a system that finds their bodies expendable, by design.

African Americans told us this when they lost Trayvon Martin, Sandra Bland, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, Eric Garner, Chinedu Okobi, Michael Brown, Aiyana Jones, Tamir Rice, Jordan Davis, Alton Sterling, Philando Castile, and so many more.

African Americans told us this after 9/11, when headlines described the US as being in a “state of terror”. “Living in a state of terror was new to many white people in America,” said the late, great Maya Angelou, “but black people have been living in a state of terror in this country for more than 400 years.”

African Americans told us this during the civil rights movement, the last time the US knew protests on this scale. And if the world paid attention to black people, then it would know that this state of terror extends far beyond the US. The Ghanaian president, Nana Akufo-Addo, captured the trauma of so many Africans around the world when he said that black people everywhere were “shocked and distraught”.

In Australia, protesters relived the death of David Dungay, a 26-year-old Indigenous Australian man who died while being restrained by five guards in 2015. He also cried the haunting phrase, “I can’t breathe.” Meanwhile, just this week, a police commissioner in Sydney said that an officer filmed casually attacking an Indigenous teenager with brutal violence had “had a bad day.”

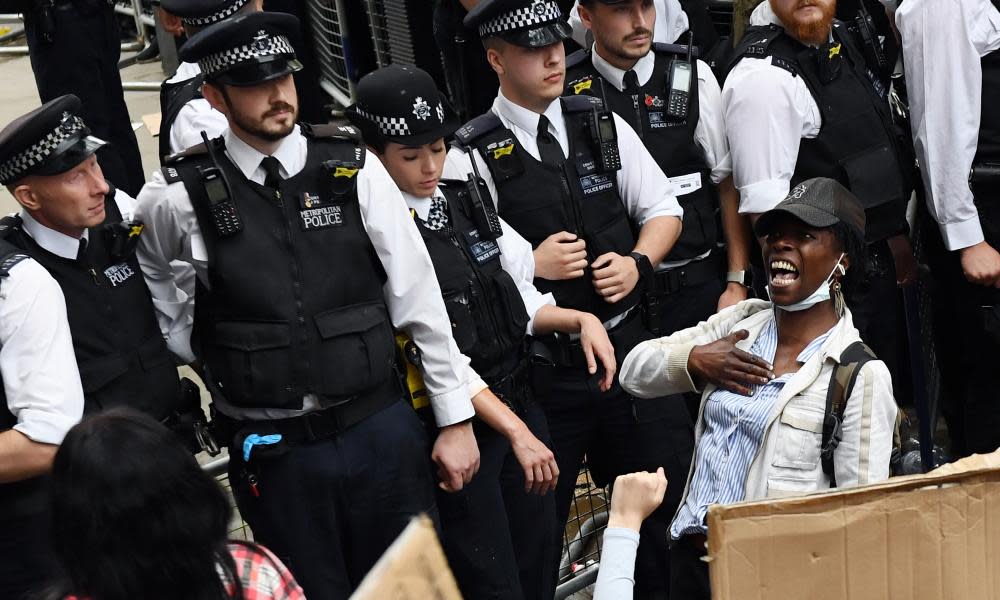

In the UK, black people and our allies are taking to the streets as I write to wake British people up out of their fantasy that this crisis of race is a problem that is both uniquely American, and solvable by people returning to the status quo.

The foreign secretary, Dominic Raab, said on behalf of Britain: “We want to see de-escalation of all of those tensions.” If he had bothered to listen to black British people, he might have discovered that many of us do not want de-escalation. We want protest, we want change, and we know it is something for which we must fight. Because many of us have been fighting for this all our lives.

The British government could have had the humility to use this moment to acknowledge Britain’s experiences. It could have discussed how Britain helped invent anti-black racism, how today’s US traces its racist heritage to British colonies in America, and how it was Britain that industrialised black enslavement in the Caribbean, initiated systems of apartheid all over the African continent, using the appropriation of black land, resources and labour to fight both world wars and using it again to reconstruct the peace.

And how, today, black people in Britain are still being dehumanised by the media, disproportionately imprisoned and dying in police custody, and now also dying disproportionately of Covid-19.

What the British government did instead is remarkable. First, it emerged that it may have used George Floyd’s death as an excuse to delay a report into the disparity in ethnic minority deaths from Covid-19. Although the Department of Health officially denies it, there were reports that the Public Health England review was delayed because of concerns in Whitehall about the “close proximity to the current situation in America”.

The government needn’t have worried, because instead of meeting the grief in our communities at so many deaths from Covid-19, its review fails to offer any new insight anyway. It has now emerged that a key section, containing information on the potential role of discrimination, was removed before publication.

The government’s response has been to appoint Kemi Badenoch, the minister for equalities, and a black woman, to “get to the bottom” of the problem. What do we know about Badenoch’s approach to racism in Britain? On “institutional racism” – a phenomenon that affects minorities in Britain – she has been reported as saying that she doesn’t recognise it . On former mayoral candidate Zac Goldsmith’s Islamophobic campaign? She helped run it. On the black community? She doesn’t believe that it really exists.

On American racism? “We don’t have all the horrible stuff that’s happened in America here,” Badenoch said in 2017.

For those of us who see racism for what it is, as a system that kills – both our bodies, and our humanity – this is traumatic. I listened to the health secretary, Matt Hancock, announce – as if it was his new discovery – that “black lives matter”, and offer someone as seemingly uninterested in anti-racism as Badenoch as a solution.

Meanwhile, that “horrible stuff that’s happened in America”?

Our reaction to George Floyd’s death as black British people is our expression of generations of lifelong, profound, unravelling pain. Some of us are speaking about this for the first time, in too many cases that I’m personally aware of, attracting reprimands and sanctions at work.

My own personal protest has been silence. Not silence at those protesting, with whom I am in full solidarity, and to whom I offer my support, my labour, my platform, my time and my resources. But a refusal to participate in the broadcast media, which – when racism becomes, for a few short days, a relevant part of the news cycle – call me in their dozens inviting me to painstakingly explain how systems of race are constructed.

This time I’m watching other black people graciously, brilliantly, appear on these platforms to educate hosts and viewers alike. And I know next time they will be asked to come again and repeat the same wisdom.

Watch: All the government support for UK businesses during the COVID-19 pandemic'

We do this work all the time. We have taken what we inherited and had no choice but to make sense of it. We have studied, read, written and understood the destructive power of race. And we are telling you that race is a system that Britain built here.

We are also telling you that as long as you send all children out into the world to be actively educated into racism, taught a white supremacist version of history, literature and art, then you are setting up a future generation to perpetuate the same violence on which that system of power depends.

We are telling you that we need to dismantle, not to de-escalate.

Pay attention.

• Afua Hirsch is a Guardian columnist

Yahoo News

Yahoo News