Raymond Briggs: Beloved illustrator who delighted millions with ‘The Snowman’

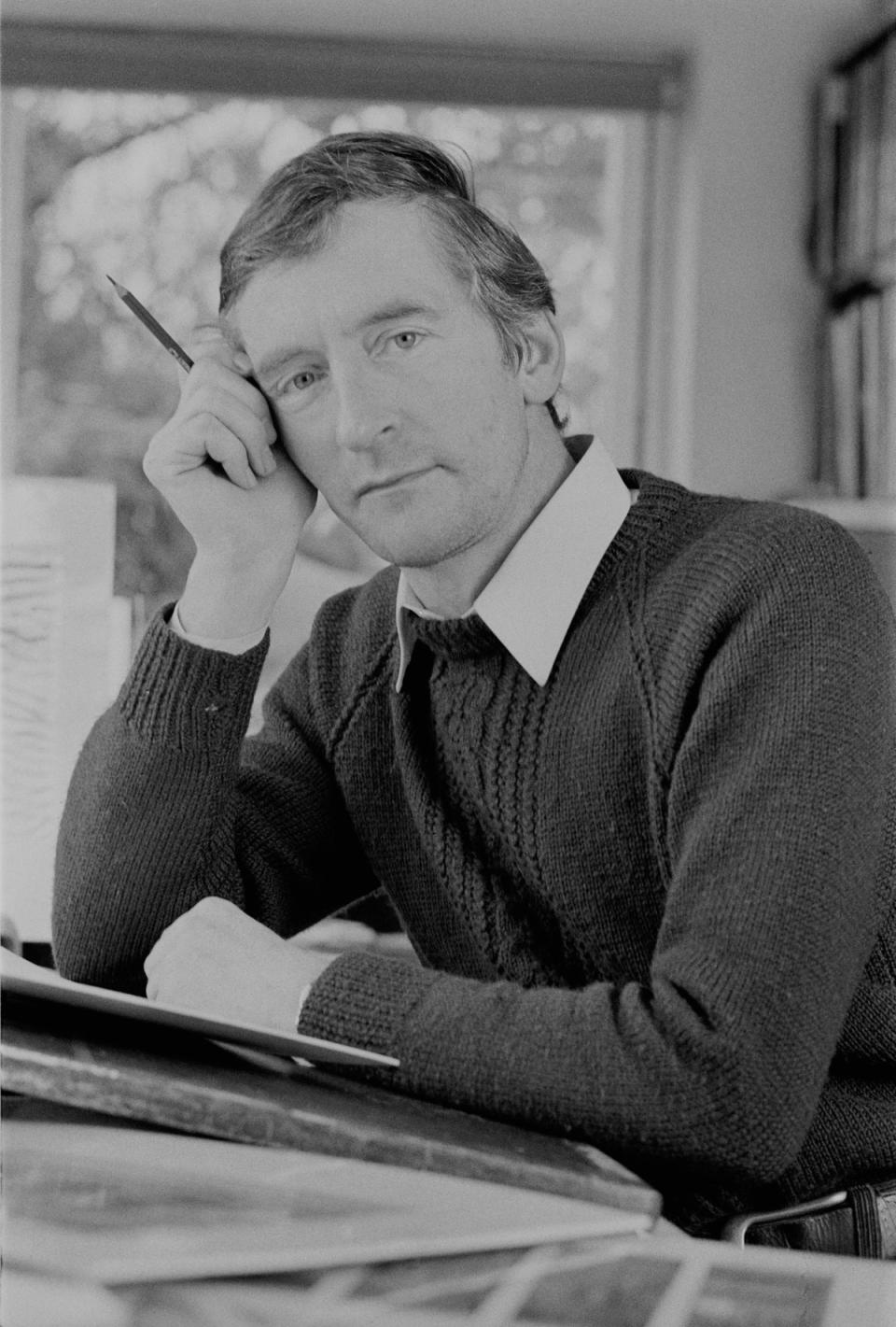

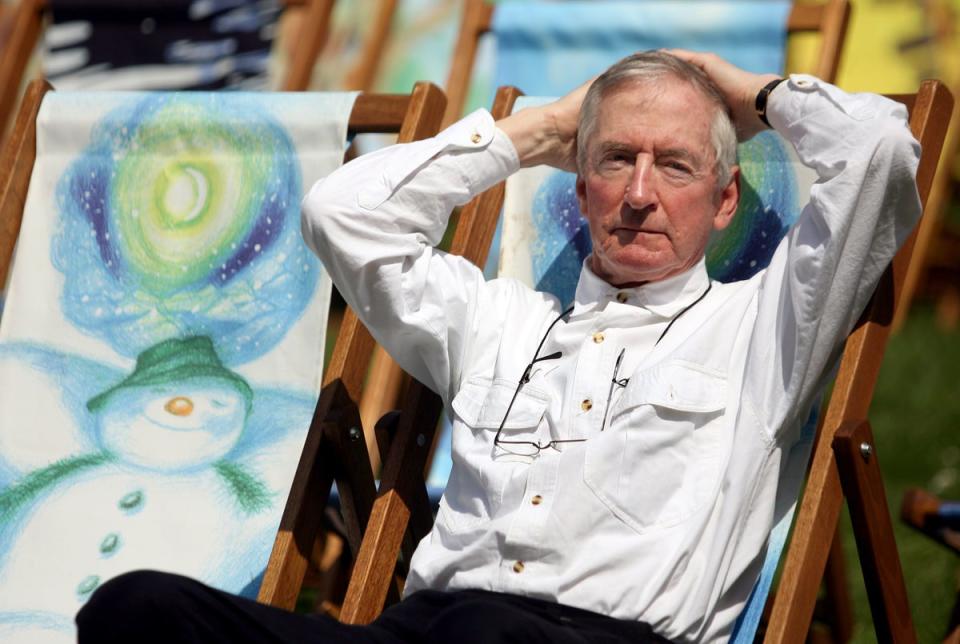

The universally celebrated illustrator Raymond Briggs, who has died aged 88, hid an essentially kind and generous personality behind the disguise of a self-styled “miserable old git”. Whether he was creating his own picture books (23 of them) or illustrating for others, Briggs breathed creative life into British children’s publishing. Laconic, loyal and hard-working, his characteristic gallows humour consistently entertained both in print and in the company of friends. His death robs the picture book world of a giant whose achievements have provided enormous pleasure to readers young and old.

Born in Wimbledon Park, London, in 1934, Briggs was the only son of a milkman and a former lady’s maid. Both parents were to appear in many of his books as symbols of an often bewildered but fundamental traditional decency at risk from changing times and circumstances. Evacuated twice to Dorset during the war to stay with “two lovely old aunties” he enjoyed what he later described as a happy but uneventful childhood.

He then won a scholarship place for Rutlish Grammar School, Merton. Already an accomplished draughtsman, he found the compulsory elocution lessons there snobbish and disliked its emphasis on his least favourite sports. When he was 15, despite parental misgivings, he enrolled at Wimbledon School of Art, hoping to train as a cartoonist. But at the interview he was told that this was not a serious or proper ambition. Opting to study oil painting instead, he concentrated on figure drawing.

As a draughtsman in the Royal Corps of Signals for his military service at Catterick Camp, Yorkshire, he was mostly required to draw electrical and radio circuits. He then completed his higher education at the Slade School of Fine Art. By now he was getting commissions from publishers and advertising agencies. Prompted by the poor quality of some of the novels he was illustrating, he produced his own The Strange House (1961), an adventure story in the Enid Blyton tradition.

This was followed by Ring-a-Ring-o’Roses (1962) and Fee Fi Fo Fum (1964), two charmingly illustrated anthologies of nursery rhymes. But he made his name with The Mother Goose Treasury (1966), a compendium of 408 nursery rhymes with 897 illustrations, some in line and others glowing with rich colour. This took him two years and won the Kate Greenaway Medal. His style here, at times lyrical, at other moments caricature, with characters always set against meticulously detailed backgrounds, was now established for life.

In 1963 he married Jean Taprell Clark, another artist who had previously been offered a career as a Bluebell Girl but chose painting instead. The couple moved to rural Sussex after Briggs was appointed part-time lecturer in illustration at Brighton Polytechnic Art School. His wife, who was diagnosed with schizophrenia and severe agoraphobia, spent some time in mental hospitals. She eventually died of leukemia in 1973. As Briggs wrote later: “Schizophrenics are inspiring people. Her feelings about nature and experiences of life were very intense.” A devoted carer, he continued to dedicate his books to her for years afterwards. Both his parents had also died the year before, leaving him at a dangerously low point.

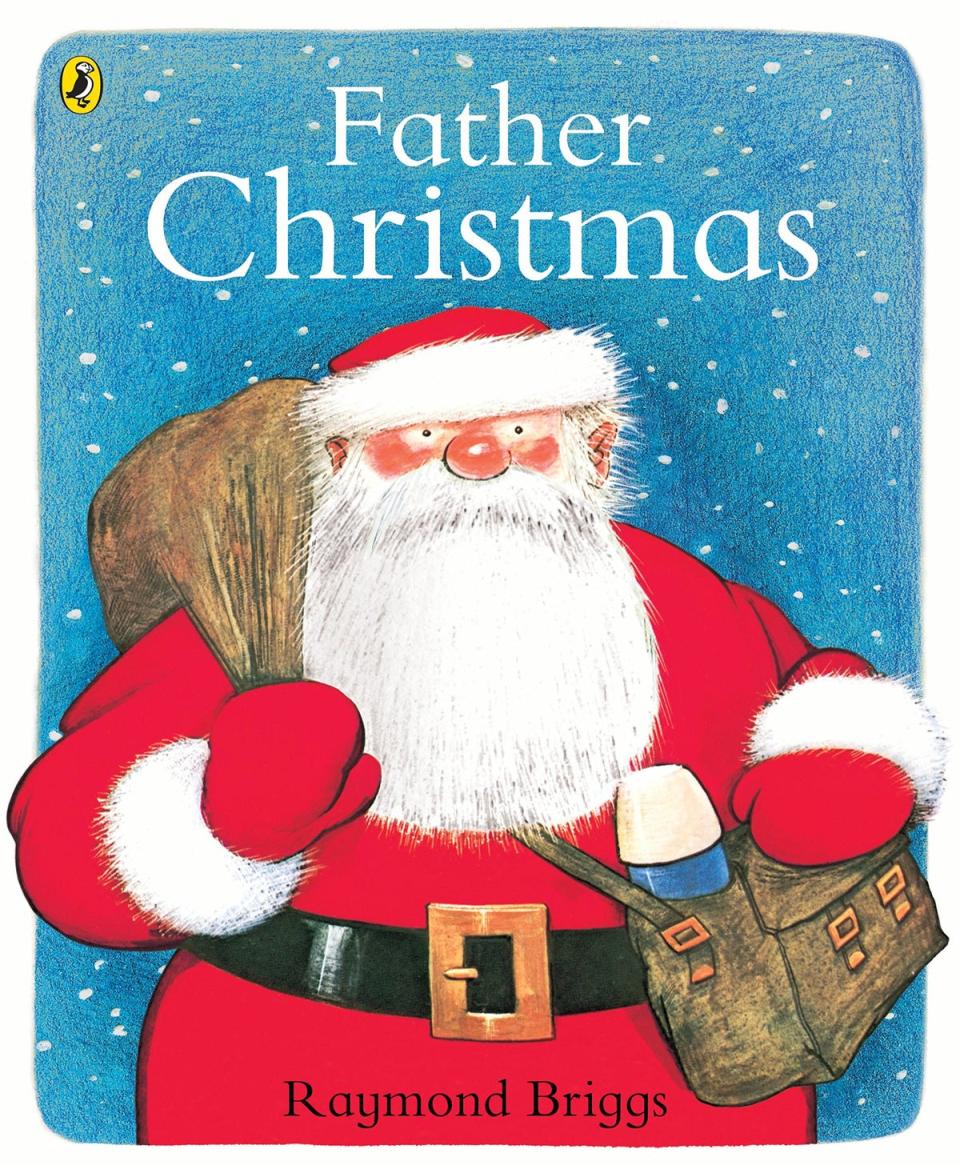

But his next big success, Father Christmas (1973) also won the Kate Greenaway Medal. Its main character is based on Briggs’s own milkman father, initially grumbling about getting up early in the cold and rain but always totally committed to his work. This loveable old man with his dog, cat and reindeer quickly became an immediate favourite. As he flies over the Sussex countryside in his sleigh at night Briggs’s own cottage at the foot of the Downs is pictured below. Illustrated in comic strip, which meant more work but also enabled him to do far more with a story than would be possible in an orthodox picture book, he could now bring all his cartoonist skills to the fore.

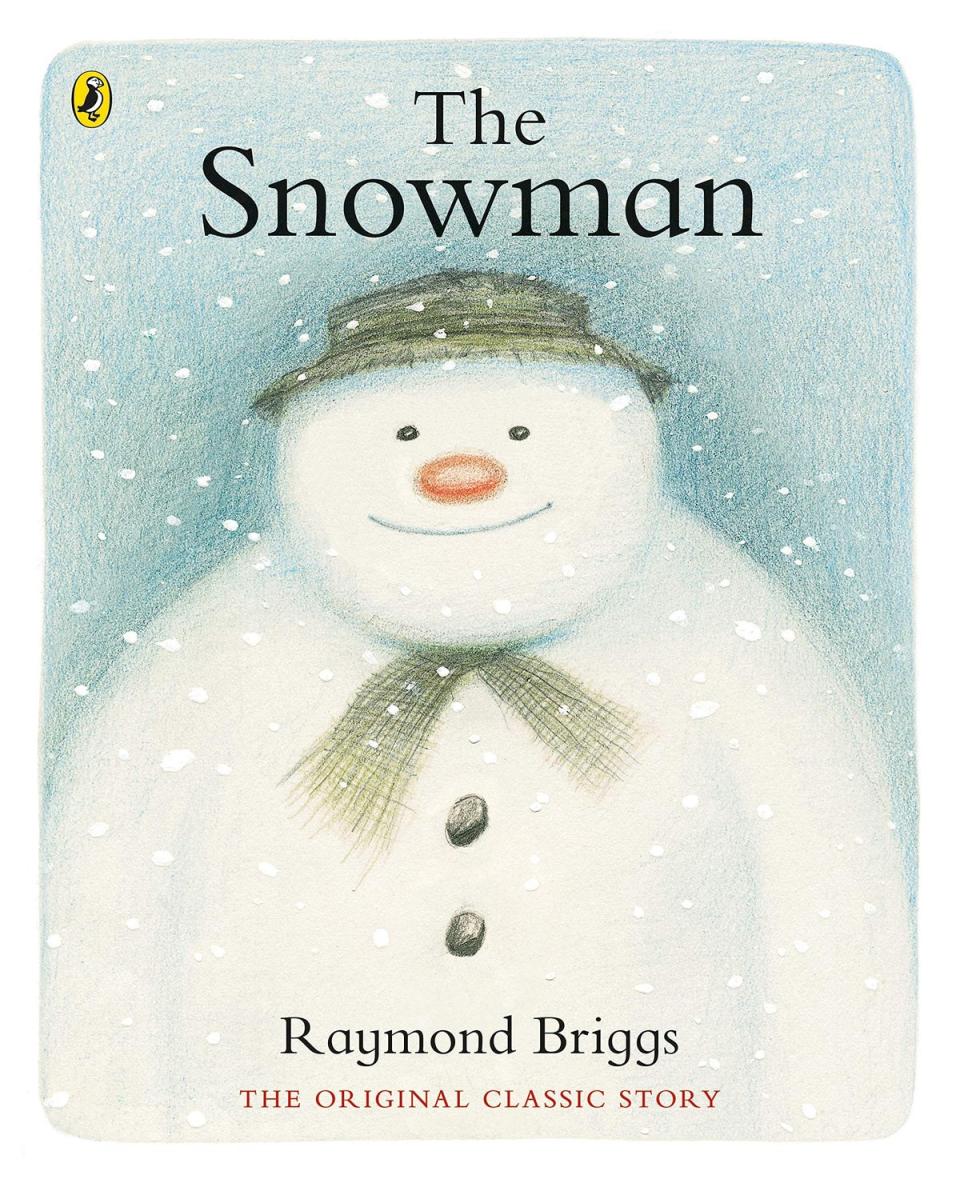

Father Christmas Goes on Holiday (1975) showed his amiable creation enjoying warm weather. The Snowman (1978), a simple and affecting story of friendship and loss, achieved global fame after it was televised in 1982 with its haunting theme tune composed by Howard Blake. Briggs used crayons rather than pen and watercolours here because he “wanted to avoid the abrupt change that takes place when a brutal black pen line is scratched on top of a quiet pencil drawing”.

Spawning other associated titles involving different technologies from pop-up to playbooks, The Snowman sold millions of copies and would have made Briggs an even greater fortune had he not previously signed away his merchandising rights. He continued to live as before, still regularly rootling through charity shops in nearby Lewes in search of second-hand clothes, “Although I draw the line at trousers.” He also liked seeking out pieces of household junk dating from the days of his youth.

Other picture books were more confrontational. Fungus the Bogeyman (1977) created an unlikely hero from a world dominated by bodily functions at their most basic. Darkly humorous, it both delighted and appalled, according to taste. The Tin-Pot Foreign General and the Old Iron Woman (1984) was a lacerating attack on what he saw as the folly and bogus rhetoric occasioned by the Falklands War. Before that, When the Wind Blows (1982) was an equally angry reaction to current government advice on how best to survive a nuclear attack. It describes in comic strip how a retired husband and wife, closely based on his parents, attempt to manage after a nuclear explosion. Not realising that what worked during the last war was now sadly inappropriate, their inevitable fate is both shocking and moving.

The same couple also appears in Ethel & Ernest (1998), a beautifully conceived and moving account, also in comic strip, of marriage, old age and death. Aimed at an audience of all ages, this was social history at its most beguiling. Also featuring the young Raymond first as a baby and later as a defiantly long-haired art student, it touched briefly on his own marriage and his move to Sussex.

Visiting Briggs at his home was an experience. Two life-size paper-mache models in the front room made by his friend and former student, the illustrator Alan Baker, depicted in lurid comic detail a bent and twisted Briggs prematurely hooked up to a catheter. A cupboard door bore a mural of his parents, with many other pictures of them elsewhere, and plastic relief of Fungus the Bogeyman overlooked an adjoining lavatory. Cartoons covered the wall plus inconsequential headlines gleefully cut out from the local paper. Visitors climbing upstairs passed five completed jigsaw puzzles of the Queen Mother. The opposite wall sported sawn-off blue plastic pipe coverings, originally left in the road by the Gas Board, now clustered together in a single frame as a take-off of the sort of modern art he abhorred.

Briggs worked each day on a large desk overlooking the Sussex Weald, doing everything, including all the lettering, by hand and never touching a computer. Abandoning ink outlines in his later work, he began making photocopies of drawings and then applying colour. His leisure time was spent in the house of Liz Benjamin, his partner for over 40 years until her death in 2015. A recently separated primary school teacher when they first met, she lived in the neighbouring village of Plumpton.

Enjoying the company of her two children, Briggs was a popular unofficial step-father, more an eccentric friend than any potential authority figure. A three-and-a half surrogate granddaughter once announced at lunch that “Raymond is not a normal person.” Delighted, Briggs declared that this sentiment must one day be recorded on his gravestone. As Liz became seriously ill in later life he was always there for her. When she was forced to move into a home, he drove 30 miles each day to visit, despite being in his eighties and unsteady on his legs.

Living to see some of his works turned into plays and with his Father Christmas character appearing on the Royal Mail’s Christmas stamps, Briggs’ last project was a “big, waffling, formless book full of pictures and quotes about death and old age”. But despite working on it for more than 10 years it never went to publication. Briggs blamed the constant domestic demands on his time for this, but there may also have been a reluctance to part with what was always going to be his final major work.

Yet he did find moments to write regular amusing columns for the Oldie magazine in their monthly Rants series. Here he could happily fulminate against a wide range of modern practices, often harking back instead to his childhood when “the morality of that time consisted in hard work, being respectable and not doing anything too outrageous”.

Briggs won numerous prizes across his career, including the Kurt Maschler Award, the Children’s Book of the Year and the Dutch Silver Pen Award. In February 2017, Briggs was honoured with the BookTrust Lifetime Achievement Award and. In 2012, the illustrator became the first person to be inducted into the British Comic Awards hall of fame.

In 2017, he was named a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) for services to literature. He is survived by his two step-children and three step-grandchildren.

RaymondBriggs, author and illustrator, born 18 January 1934, died 9 August 2022

Yahoo News

Yahoo News