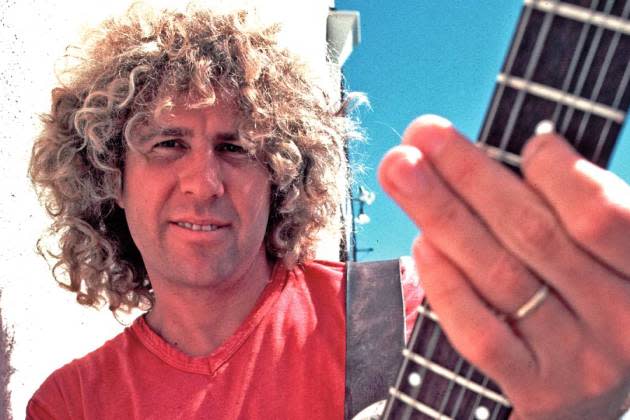

Sammy Hagar Reflects on Red Rocker Roots and How Fontana Hometown Shaped His Art

They say, “If you remember the ’60s, you weren’t there,” but newly minted Hollywood Walk of Fame honoree Sammy Hagar not only remembers the ’60s, but the ’50s as well. As someone who grew

up in that same era in Hagar’s hood, the former hometown of America’s biggest steel mill west of the Mississippi and birthplace of the Hells Angels — Fontana — I can attest to the veracity of Hagar’s crystal-clear total recall.

Now a bustling metropolis (well, bustling mostly with logistic centers aka shipping warehouses,) back in the ’50s Fontana had a population of just under 10,000 and Kaiser Steel had a payroll of about that same number. It was more “Deer Hunter” than “Surf’s Up,” with a richly diverse blue collar, working-class hamlet of transplanted Rust Belt Slovenians, Hungarians, Czechs, Slovaks, Italians as well as Dust Bowl refugees, Black people and Latinos.

More from Variety

Sammy Hagar Says Final Phone Call With Eddie Van Halen 'Broke My Heart, But Thank God We Connected'

Sammy Hagar, Gene Simmons, Lenny Kravitz and More Mourn Eddie Van Halen, the 'Mozart of Rock Guitar'

Sammy Hagar Joins Rob Thomas for 'Smooth' Performance (Watch)

The story of the “Red Rocker” Hagar is the story of a West Coast artist who may go south to make great tequila, or north to vibe with the ’60s and ’70s Bay Area hipsters or swing west to join the boys from Pasadena in Van Halen, but his soul is Pacific Ocean Blue.

Most important of all, Hagar — whose career not only includes stints in great bands like Montrose and Van Halen and a successful restaurant chain and tequila brand — has roots planted in the soil that once featured bounteous citrus groves, almond and peach orchards and sprawling grape vineyards. The Rock and Roll Hall of Famer has ample, sharply recollected fond memories of his Fontana (aka Fontucky) youth and his musical coming of age there.

“I loved growing up in Fontana,” says the seemingly eternally ebullient Hagar. “If you think about it, it’s got an incredible location: an hour to the mountains, to Joshua Tree, to the beach, to Hollywood. My friends and I used to pool our gas money and head out to all those places. I loved the mountains in the summer and the desert in the winter. I started out as a greaser but then I got hip and became a hodad. I got white shoes and white jeans and started to spend my time at the beach.”

With two older sisters, the pre-teen Hagar joined the 1950s rock and roll revolution.

“I got caught up in Elvis,” Hagar recalls. “I had a paper route, and I bought my first single, which was Elvis’ ‘Big Hunk of Love.’ I didn’t even have a record player! I just stared at the label! My big sisters used to comb out my hair and I pretend I was Elvis.”

A few years later, Hagar was rocking on stages around the Inland Empire, long before he made the trek up the coast in 1969 to San Francisco and wound up with a major label deal as a member of hard-rock outfit Montrose in the 1970s.

It all started, as we so many nascent ’60s rockers, in 1964, when the Elvis allure faded and the British Invasion kicked into high gear.

“The Beatles led the British Invasion happened, but what really got me was when the Rolling Stones hit. They looked like tough guys from Fontana. I had an older friend, Ed Matson, who played guitar well and helped me learn all those Stone songs,” Hagar says.

“I remember, he asked me, ‘How do you remember all those lyrics?’ I can still do it. I remember all my lyrics and always have. So, I could sing all those Stones hits. [Editor’s note: Including “Route 66!”] Somebody said, ‘Let’s start a band and pretty soon we had our set of seven or eight songs, which included a couple of surf songs for the locals. But I was also a soul music guy. I was into James Brown and Hendrix. And I actually saw Otis Redding at the Monterey Pop Festival. I went there, not to see the rock groups, except maybe Eric Burdon, but I wanted to see Otis!”

Down the road, in Hawthorne, California, Brian Wilson’s Beach Boys were the American answer to the Beatles. The surf may have been an hour away, but surf music was lapping up on our Inland Empire shores.

“I used to go to the National Guard Armory in Riverside to hear Dick Dale. Around that time, I got in a band called the Fabulous Castiles and we used to play ‘Surfer Stomp’ at Brunton Hall in Fontana. We didn’t even have a drummer and we all played through one amp. The Justice Brothers came later and that’s when I wanted to get serious. We tried to make a living by playing in bars.”

As we compare notes on our teen years in the Inland Empire, my own recall kicks in and I realize that before I saw Hagar with his band the Justice Brothers at the Night Club in San Bernardino, I caught his act at a Battle of the Bands in the mid-1960s at a Fontana Shopping Center, when he was fronting a soulful combo colorfully called the Mobile Home Blues Band. “Our dream,” Hagar recalls, “was to live in a motor home and drive up and down the coast playing our music.”

The motor home adventures didn’t happen, but the Mobile Home Blues Band scored an early Hagar victory: “We actually won one of those battles of the bands and the first prize was a Vox white teardrop guitar white teardrop guitar. It’s exactly the same one that Little Steven (Van Zandt) has today!”

In those days, everywhere Hagar turned, there was an influence that could get the future Red Rocker’s motor running. For instance, Hagar describes the aforementioned Justice Brothers as “a soul band.” He recalls their repertoire consisting of “Tower of Power, Otis Redding, Wilson Pickett and maybe we’d thrown in a Who song like ‘Behind Blue Eyes.’”

Digging deeper, Hagar delineates the fine points of 1960s rock iconography.

“‘Meet the Beatles’ changed the world, but it was the Stones for me. They changed the way I looked. Every time I joined a band, I wanted to be Keith AND Mick. Then, in my heart, I wanted to be Jimi Hendrix. Then I wanted to be Jeff Beck, but not the later-era Beck. That guy was too good. I can’t play like that. I wanted to be the Jeff Beck Group Jeff Beck. AND Rod Stewart. The two guys from that album ‘Truth.’ And I rode that bus until I heard Bob Dylan’s ‘Like a Rolling Stone’ and I realized how important lyrics are. And then I started writing my own music.”

Hagar, one of hard rock’s preeminent showmen, makes a surprising admission about his softer side.

“Around the time of Dylan, I also got turned onto Donovan and to be honest, I was more of a Donovan guy than a Dylan guy. Donovan had the same feelings as I had about lost love and had a romantic streak I identified with. I actually cut a version of his song ‘Young Girl Blues’ on my first solo album. I’ve met him and I still love his music. He’s a great poet.”

Once Hagar split from Southern California and took his act up the coast to the Bay Area, he blended well into the Haight-Ashbury peace and love scene.

“The Grateful Dead were playing in the park for free and I wanted to be part of that. I became a hippie. I could sleep on people’s floors. No problem! I had my guitar and I wanted to play and sing, so I fit right in, except I was never a heavy drug guy.”

Soon, Hagar put away the love beads as success and fame first beckoned when he was invited to join guitar virtuoso Ronnie Montrose’s band Montrose on Warner Bros Records. The ‘60s were over and new musical influences were wafting through the streets of San Francisco.

“I saw David Bowie, Alice Cooper and Marc Bolan and all the glitter rock guys, and I loved all of them and I thought, ‘This is the future,’” says Hagar, ruefully adding, “But I was getting too glittery. I called myself Sammy Wild for a while. Ronnie was stripped down and that was the right way to go.”

As his time in Montrose drew to a close in the late 1970s and Hagar was segueing into a solo career, he found a new music hero who combined the raw soul of Hagar’s rhythm and blues heroes, the sharp edginess of Dylan and the deep, thoughtful romanticism of Donovan: Irish soul legend Van Morrison.

“Then it was Van Morrison,” says Hagar. That’s who I wanted to be. Bowie came and went, but Van remains. One of my best songs, which I just wrote recently, ‘Father Time,’ really has my Van Morrison influence all over it.”

The Red Rocker and the Belfast Cowboy crossed paths in the Bay Area, which led to Hagar’s version of Van’s mid-’70s gem “Flamingos Fly.” According to Hagar, there was a version of him and Van doing the song as a duet, but “Van made me take his voice off it.”

Sigh.

As the decades of rock progressed, bands that dared pomposity in their arrangements (think Yes, Emerson, Lake and Palmer, King Crimson) or snappy costumes (such as pre-Hagar Van Halen) were in the crosshairs of the nascent, gnarly movement out of England called “Punk.” Which a decade later had morphed into “Grunge.”

Hagar explains an important aspect of his personality that has played a key role in his continual growth and evolution as an artist: “I’m a white light, positive energy guy. I’m not bitter, I’m not angry. “

“When I saw the Sex Pistols at the Winterland [in 1978] cutting themselves, spitting on each other, they scared me. I couldn’t be farther away in outlook. But I immediately thought ‘This must be the future.’ What I think went wrong was that they were discovered too early. They needed to develop more. But what mattered was the ‘You’re all full of shit’ rawness. That was what they were selling, and it was simple and real.”

By the time the Seattle grunge got the rock music world all shook up in the late 1980s, Hagar was the lead singer of Van Halen, one of the world’s biggest bands, but he was open to the sounds and felt a kinship with the young West Coast artists who, like him, were trying to express themselves through the wonderfully powerful medium of rock and roll.

“Kurt Cobain had a profound influence on me. As soon as I heard and saw grunge, it was like ‘I’m a Fontana guy. LET’S GO.’”

“Cobain said in interviews that his first concert was Sammy Hagar at the Tacoma Dome. But when grunge really hit, a lot of the young guys coming up were throwing rocks and we were one of the biggest bands in the world. But it was easy for me to go back to my roots, playing barefoot and in shorts, not all dressed up like when we went the wayward way! I saw Alice in Chains and said, ‘Let’s take them on tour with us.’”

More than the music perhaps, the tragedy of Cobain had a profound impact on Hagar, whose self-described “white light” outlook never blinds him to the realities of life learned early, where the young Hagar faced personal darkness in sunny Fontana.

In his autobiography, “Red,” Hagar vividly details his hardscrabble early days when his family’s very existence was threatened by the raging alcoholism of his ex-boxer father. I suspect that the pungent blossoms of my memories of the long-gone Fontana orchards may not be as romantically remembered by Hagar.

Hagar’s mother had to drive the kids into the protective cover of the orange groves to hide from the violent man whose life ended drunk and hand-cuffed in the back of a Fontana police car.

The tough love anthem “Don’t Tell Me (What Love Can Do)” is Sammy’s painful, yet moving elegy for Cobain and a potent example of how Hagar’s personal songwriting canon contains a lot more than

Sammy’s better-known shots-til-you-drop Southern California paeans to puberty and partying:

It’s OK, I’ll do what I want/I can drive/I can shoot a gun in the streets/ Score me some heroin./I can jump/ Be the sacrifice/ Bear the cross just like Jesus Christ/And I don’t wanna hear/What love can do.

Those words were written in a troubled time in Hagar’s life, when the speeding Van Halen megaband train derailed.

Like every other turn in Hagar’s long and winding California road, this one led to some incredible successes, many of which seem to only be growing in a multitude of musical adventures and business initiatives. One of the most exciting, to this former IE kid at least, is Stage Red, Sammy’s new theater in Fontana.

So the story doesn’t end in the orange groves or in a mobile home or lonely out on the dark desert highway those other Californians like to sing about.

Sammy Hagar and the Hagar Family lived, and prospered, with Prodigal Son Sammy in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and somewhere way up in the high rankings of those Forbes celebrity lists. One report has Hagar personally pocketing $125 million for selling his share of the Cabo Wabo brand — long before, we should add, the record will show, a man named Clooney scored big with a rival libation.

Revisiting Fontana with Hagar is a blast, but revisiting Hagar’s body of work yields a rich and newfound appreciation for the depth of feeling and ambitious, restless energy of a California artist who even had a hit record about not accepting any speed limit other than his own.

From his affecting take on ‘Young Girl Blues’ on the first solo LP, up to his recent plucky, pensive and perfectly beautiful ‘Father Time,’ Hagar has always had more than one gear.

In his late 70s, is Mr. “I Can’t Drive 55” slowing down?

Out here on Route 66, it doesn’t look that way.

Sammy’s “Best of All Worlds” tour, which features Hagar along with rock superstars Joe Satriani, Michael Anthony and Jason Bonham, slams into the Kia Forum in Inglewood this summer. If you’re keeping track, that’s nearly 60 years and exactly 67 miles from the Fontana Square Shopping Center Battle of the Bands where “All” started.

Best of Variety

Sign up for Variety’s Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News