Scientists baffled over prehistoric tree mystery

Trees that grew more than 300 million years ago had a far more complex structure than their counterparts today, research has shown.

The earliest trees had an astonishingly intricate anatomy for reasons scientists do not understand.

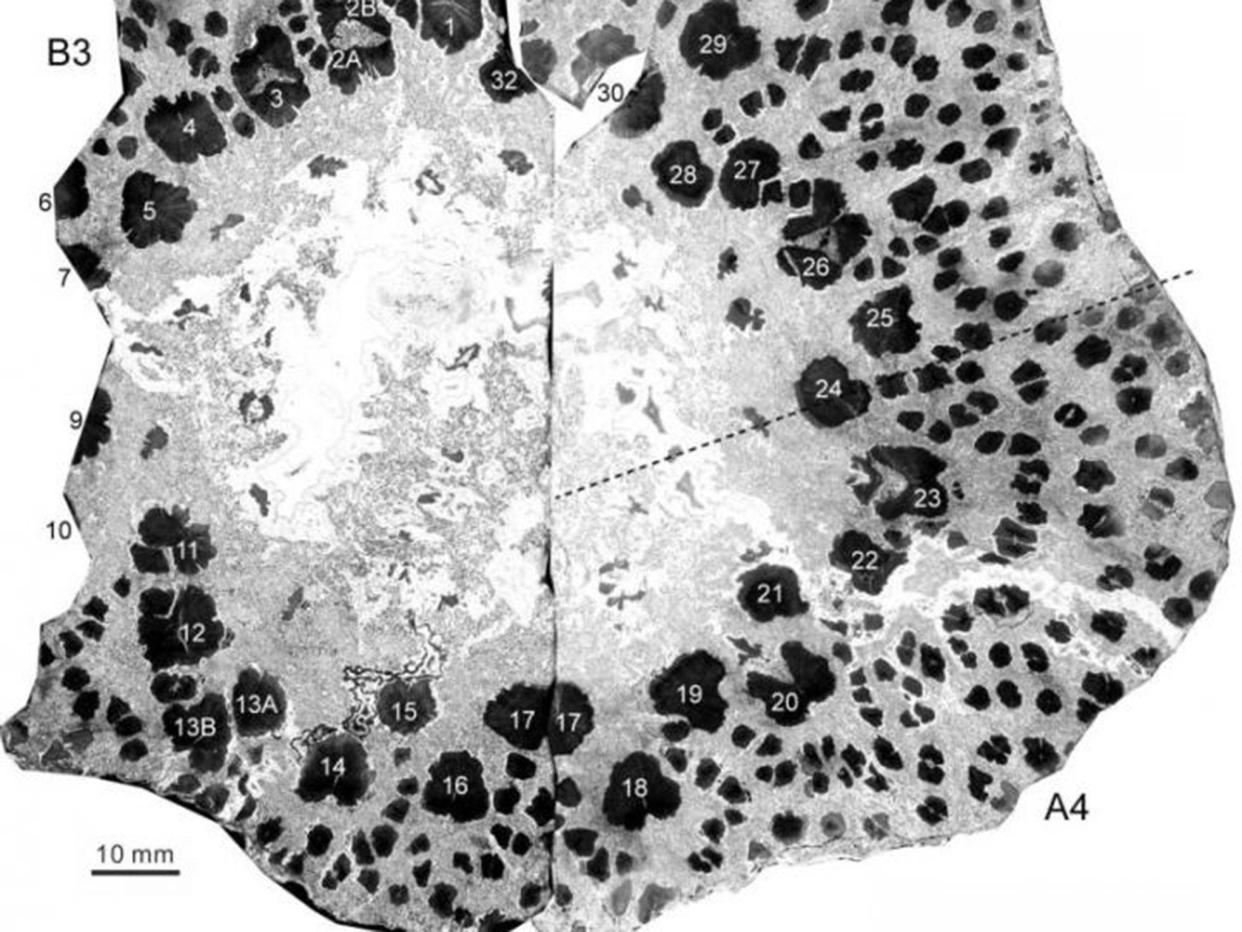

Scientists examined the exceptionally well preserved fossilised trunk of a 374 million-year-old cladoxylopsid tree from Xinjiang, north-west China.

What they found surprised them.

All trees have straw-like woody strands called xylem that conduct water from the roots to the leaves. New layers of xylem in most trees produce the familiar growth rings in trunks and branches.

But the new fossil discovery showed that the earliest trees had their xylem confined to the outer 5cm of the trunk while the middle was completely hollow.

The strands were interconnected like a finely tuned network of water pipes. And rather than the tree laying down a growth ring under its bark each year, each xylem strand generated its own growth ring. In effect the xylem strands behaved like individual mini-trees.

As the strands expanded, connections between them split apart and the diameter of the tree trunk widened.

Dr Chris Berry, one of the scientists from the University of Cardiff, said: "There is no other tree that I know of in the history of the Earth that has ever done anything as complicated as this. The tree simultaneously ripped its skeleton apart and collapsed under its own weight while staying alive and growing upwards and outwards to become the dominant plant of its day.

"By studying these extremely rare fossils, we've gained an unprecedented insight into the anatomy of our earliest trees and the complex growth mechanisms that they employed.

"This raises a provoking question: why are the very oldest trees the most complicated?"

Dr Berry previously helped uncover a fossil forest in Gilboa, New York, where cladoxylopsids grew more than 385 million years ago.

But no earlier examples of the tree fossils compared with the latest one from China, he said.

"Previous examples of these trees have filled with sand when fossilised, offering only tantalising clues about their anatomy," said Dr Berry. "The fossilised trunk obtained from Xinjiang was huge and perfectly preserved in glassy silica as a result of volcanic sediments, allowing us to observe every single cell of the plant."

The research is reported in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

PA

Yahoo News

Yahoo News