Is seeing believing? How documentaries are taking liberties with historical truth

When I was five years old, my parents arranged for a local photographer in Maidstone to take a portrait picture of their beloved son. A tall gentleman arrived at our home in Bower Mount Road and photographs were duly taken of your correspondent perched on the sofa in our family sitting room. But my mother wanted some more natural snapshots of little Robert playing with his toy trains on the floor. In those days, expensive photographers not only turned up with tripods and huge black cameras. They also ‘colourised’ their completed photographic prints – and thus sent back the finished product after painting, with water colours, little Robert’s blond hair, pink cheeks, blue pullover and brown sandals.

I was outraged to discover, however, they had muddled the livery of my train set. My fine green-painted London and North Eastern Railway steam loco and trucks had been changed to red. A miniature Great Western loco also appeared in red when it was in reality grey. In those days, like many other five year olds, I was planning a career as a steam engine driver – I already had piles of Ian Allan train-spotter books – and this wilful, lazy photographic distortion of the one trade I took seriously was deeply insulting. I have a faint memory, which my mother later confirmed to be true, that I demanded the photos be sent back to the photographers to be repainted in the real regional colours of my train set, or simply restored to monochrome. Better black and white than this grotesque distortion of reality.

Which is almost exactly what a few dissidents said of Peter Jackson’s “colourisation” and treatment of the black and white Imperial War Museum footage used in his wondrous They Shall Not Grow Old film of the 1914-1918 war. Some of the Great War material used by Jackson was on an epic scale – the soldiers walking across the vast fields of the Somme towards the end of the movie, for example, or the anxiety on those living faces of the future dead as the soldiers of the British empire prepared to go “over the top” – and left me feeling (yes, of course) that I was there. Or if not there, that these men were just like me, would have spoken in accents I would immediately understand, looked like me or my dad (who actually was in the Great War). They were – if I can put it like this – “as of us”.

For years after the colourisation of my train set – however inaccurate it was – my mother would vainly try to explain to me that the colours, however wrong, added authenticity to the picture. And of course this is what the colourisation debate in Jackson’s film, the discussion about actors reciting lip-reading words, and the treatment of footage to “slow” the movie to “real” time – note the repeated need here to use quotation marks – is all about.

It’s not so much whether the colours are 100 per cent “correct”. Jackson could only do his best. What he was trying to do was to bring the past closer to us by adding an authenticity – a “truth” of reality – which was missing from the black and white images. He was not fiddling with the authenticity of the original film; he was enhancing it.

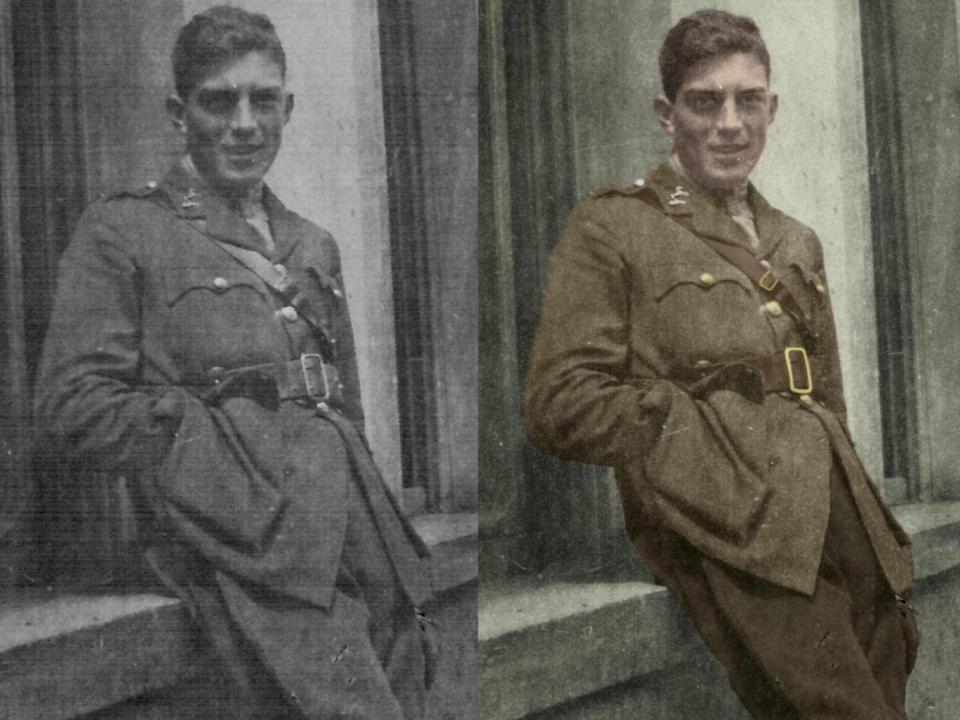

Years ago, when rough-and-ready colourisation was originally used on First World War material – it began, I recall, on French archive footage – I would point out that, with all its faults, it was closer to the reality which my own father experienced. After all, 2nd Lt Bill Fisk of the King’s Liverpool Regiment very definitely saw the third Battle of the Somme in colour – with his own eyes. “Cones” in our eyes allow us humanoids to receive images in colour. Films didn’t have that ability. When he entered the burning city of Cambrai with Canadian troops in 1918, Bill surely looked upon flames that were red and gold, not white-and-grey against black, which is how they appear on the only film stock of the actual event.

There were a few forgivable lapses in They Shall Not Grow Old – and not just the slight mangling of the line from Binyon’s poem, For the Fallen (“They shall grow not old”), which somehow suggests a more nuanced emotion. The legion of undamaged British tanks which move majestically across the screen in colour were originally photographed not in action but in a pre-battle demonstration. Some of the “action” sequences were contemporary enough, but probably posed behind the lines. At least Jackson was not fooled by the clip of contemporary fake footage – used on dozens of occasions in other “authentic” films of the Great War battles – in which a single British soldier falls to the ground as his comrades cross the barbed wire on the frontline. Patient editors later noticed that the “dead” soldier, a few seconds after his martyrdom, crossed his legs for greater comfort. Real coloured red warning lights here.

Cheaply made docs which often turn up on little-known satellite channels have recently included British artillery batteries on the western front – I know the actual footage very well – to illustrate barrages in Gallipoli and on the German eastern front in the First World War.

Some of the most remarkable footage used by Jackson showed real shells bursting over a real British frontline. The sound of the explosions was – and I use personal experience here – just like the real thing. And it’s interesting to recall that for decades, archive film – not just of the First World War but of naval displays, village fetes, funerals and early 20th century tourism – has almost always been accompanied by “sounds-off”. You would hear the clip-clopping of horses or the music of bands or the muffled but necessarily indecipherable chit-chat of crowds. Oddly, no one, so far as I know, has ever complained about these utterly fake – really fake – soundtracks.

Twenty years on, a lot of Second World War footage, interestingly enough, whether in real colour or crudely colourised much later, was either silent or of poor sound quality. So Panzer tanks or Stukas had their roars and wails magnified or transposed from other footage which contained better sound quality but poorer pictures. Ergo air raid sirens often sound suspiciously identical. Some are indeed identical.

An obvious problem, of course, is posed by poor-quality film. When confronted by the no man’s land horrors of the actual 1916 first Battle of the Somme, Jackson was reduced to using the actuality of real soldiers waiting for combat alongside the real archive voices of now dead but real participants (recorded long after the war): but to illustrate the hand-to-hand fighting, he used illustrations from contemporary war magazines. There is, as Jackson must know, actual Imperial War Museum film of the British Army’s advance from the Somme frontlines – used years ago in a BBC film about the battle – but the soldiers are tiny insects on the screen, indistinct amid the vast grey (sic) landscape and too far away to show their suffering and loss. I didn’t spot a frame of this in Jackson’s film but I don’t blame him for omitting this footage. Colourised or “soundised”, as he may have treated it, there would be nothing in these real contemporary images to suggest shellfire, death and calamity. Which is why Great War cameramen found it more convincing to restage the battles afterwards.

But now I come to a far more serious problem. Jackson, so far as I could see, didn’t fall for this at any point in his film. But many documentaries on the Great War – and the 1939-45 conflict for that matter – bowdlerise and misuse archive footage to “fit” the narrative of their story. When Jeremy Paxman made a short series on the First World War – again, an excellent production for which no filmic blemishes were Paxman’s fault – he talked about the British soldiers of 1914 and the first British Expeditionary Force of 1914, regular soldiers who were wiped out at Mons and subsequent battles of that year. But the footage which accompanied this part of Paxman’s description showed British soldiers wearing steel helmets.

We are all familiar with these anti-shrapnel helmets – they looked like upturned washbasins or kitchen dishes – on the heads of the Tommies in the Great War; you can see them on the bronze heads of soldiers on almost every UK war memorial. A few of these Brodie helmets, produced after British soldiers had received frightful shrapnel wounds to the head, reached the western front in the autumn of 1915 but, so far as I know, they were not filmed until the great battles of 1916. So the moment in the Paxman film where we see the helmets was inaccurate. More than a year separated his commentary from the film. A small flaw in a fine production, you may say. Correct. But where does this end?

French editors often flaunt the accuracy of their own historical documentaries – rightly, in my view – by superimposing a small logo on the top left of the screen when showing archive footage. This illustrates the actual provenance of each film clip – CNC French film archives of the First World War, for example – and reassures viewers that what they are watching is indeed the “real thing”; or at least that they know who to blame if it isn’t. But over the years I have noticed how unmarked historical footage has more and more frequently been injected into First World War documentary films with ever greater inaccuracy. Cheaply made docs which often turn up on little-known satellite channels have recently included British artillery batteries on the western front – I know the actual footage very well – to illustrate barrages in Gallipoli and on the German eastern front in the First World War.

Inevitably this habit has leached over into Second World War documentaries. Only three weeks ago I watched film of a building collapsing during the 1940-41 London blitz – in Victoria Street, I believe – used to illustrate the destruction caused by Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union. Mixed in with real German footage of the June 1941 attack and Russian archival material, which I suspect was of Soviet troops at Stalingrad well over a year later, it married up seamlessly as a war documentary about Hitler’s Operation Barbarossa. But the images – far from being colourised or having sounds added – were simply jumbled up together without any academic rigour or accuracy. They were plain wrong.

I know the excuses for this. The images were “generic”. They came from the Second World War and – even if the film showed events separated by a year or two, or which occurred a few thousand miles apart – they all illustrated the destruction Nazi Germany inflicted on the world. But the makers showed no interest, understandably, in explaining this. Viewers, many perhaps not greatly interested in history or the Second World War, were left to believe that the scenes they watched accurately portrayed, as well as reflected, the actual historical facts narrated on the film. But this was not true.

Ironically, Leslie Norman’s 1958 feature used real footage of Stuka dive-bombers [as he] could not afford the real Stukas that later war epics could refly or destroy. Now documentaries are dipping into feature films to make up for their lack of real archive footage

In 1993 I came across a very up-to-date version of this same phenomenon when I helped make a three-part film series about the Muslims of the Middle East called From Beirut to Bosnia for Channel 4 and the Discovery Channel. Readers can see the movies today on YouTube, but one of the many sequences we had to drop during editing – the three films, after all, totalled almost two-and-a-half hours of running time – was a revealing interview with a CNN reporter in Jerusalem.

Our own crew and I had been filming in Gaza a little earlier, where Palestinian youths could be seen throwing stones at Israeli troops. They had been protesting after the killing of a Hamas fighter by Israeli soldiers – who had then visited collective punishment upon all the Palestinian civilians in the area by destroying their homes with explosives. That same evening, by chance, the Jordan-Palestinian negotiating team, including Hanan Ashrawi, returned to the West Bank – not Gaza – from Washington, with little progress made in the pre-Oslo “peace process” talks. In its report that night, CNN described the outrage of Palestinians at this situation but then showed their own footage of the youths throwing stones in Gaza. The problem, of course, was that these same young men – who you could clearly see in the film we had taken – were not complaining about the peace talks at all, but about the Israeli destruction of their homes. When I questioned the CNN representative about this curious conflating of two entirely different stories, he replied – smiling, I recall – that CNN’s report used “generic” footage.

But this was a very serious matter. If an angry Palestinian response to political talks was to be illustrated by scenes of violence – because the film used was “generic” – then the message was even more disturbing: that the Palestinians were a “generically” violent people whose only form of political opposition could be achieved through stone-throwing; even though the stone-throwing in question had nothing to do with politics but with an act of cruelty by the Israeli army. In our film series, you can see the youths opposing the Israelis in the streets of Gaza. But our CNN interview, like so much other material, was cut because we wanted to use up precious minutes on the dispossession of a Palestinian family for a Jewish colony on the West Bank.

Conflation of a different kind took hold of documentary filmmakers in the years after the Second World War – and right up to today. Satellite channels have saturated viewers with cheaply made “docs” of the war which show little interest in the provenance of film clips. Several times in the past three years, for example, I have seen films on the 1940 British evacuation from Dunkirk – supposedly documentary footage, and nothing to do with Christopher Nolan’s award-winning movie Dunkirk last year – which included sequences apparently taken on the beaches of the French port city during the German bombardment of British soldiers amid the sand dunes. These sequences, however, were very clear black-and-white shots of great drama – and with none of the scratches and “grain” quality of original footage.

Amid the chaos of the real defeat in 1940, of course, there was understandably little archive film of the evacuation; a clip taken from a British Army vehicle entering the burning ruins of Dunkirk with wrecked military trucks lining the pavements; some Pathé footage of warships crossing the channel; of the “little ships”; of soldiers in the water, taken from a small vessel inshore, a derrick in front of the camera and sand dunes in the background; and of the survivors being taken ashore at Dover and fed through the windows of a passenger train in Kent. As a Kentish man myself, I can identify the station as Headcorn; you can even see the platform to the old branch line to Tenterden in the background.

But those even more dramatic and very powerful non-grainy pictures in the latter-day documentaries stuck in my mind – until in Beirut I happened to rewatch the old John Mills movie Dunkirk, directed by Leslie Norman in 1958. It’s a very compelling feature film, with uncompromising scenes of suffering and cowardice quite unusual in such early postwar movies, and the beach scenes were shot not on location in Dunkirk like Nolan’s epic – nor in Redcar, where Dunkirk is restaged in the famous unedited five-minute sequence in Joe Wright’s Atonement – but on Camber Sands in East Sussex. The beach scenes are graphic and perfectly posed. And quick as a flash, I recognised them. They included the brief inserts that had been used in those “documentary” Dunkirks I had been watching on television.

Ironically, Leslie Norman’s 1958 feature used real footage of Stuka dive bombers along with that equally genuine film shot from a British Army truck outside Dunkirk. Norman could not afford the real Stukas and burning cities that later war epics could refly or destroy. So he dipped into archive material to make up for the lack of props. Now documentaries are dipping into feature films to make up for their lack of real archive footage.

The original appropriation of fictional Dunkirk for real Dunkirk was probably the work of some amateur documentarymaker way back in the 1970s or 1980s who knew little and cared less about the Second World War; he or she spliced in a few feet of the movie, and it stayed in the loop when others with equally little interest in history wanted to use the footage.

More recently, however, we have been confronted by the “recreation” or “re-enactment” of events, woven into documentary footage. I find this both outrageous in terms of visual accuracy and demeaning to the viewer. Only a month ago, I was watching a fine two part series on the German invasion and occupation of Poland in the Second World War. Fine, that is, except for the immature and poorly acted sequences in which named individuals – who, in the case of the filmmaker Roman Polanski, actually appeared in the film in person – were shown in theatrical interludes between rare archive footage, in which poorly cast actors played out supposedly wartime scenes with a third-rate script and utterly predictable scenarios. How many times can theatrical fathers go off to war, bidding their children farewell, along with a commentary that this would be the “last time” they would ever see their fathers again?

This is a difficult subject because few have questioned the “rules” which must apply in future if we are to safeguard the authority of documentary and archive footage. In the past 24 hours I’ve watched for the first time Christian Frey’s fascinating 2015 documentary Hitler’s People, made for Germany’s ZDF channel and based on the experiences of former US psychological warfare officer Saul Padover. Advertising for the film announced: “Evocative and previously unseen archive footage, much of it in colour, shows life in Nazi Germany from 1933 onwards till the end of the Nazi regime in 1945 as never before.”

Yet this very same film – whose archive footage is indeed real and extraordinary – includes chunks of crudely re-enacted scenes in which an actor playing Padover supposedly talks to former Nazis. One of the internet advertisements for Hitler’s People shows a still from one of the “re-enactments” rather than the archive. In fact the recreated Padover scenes are shot in a dull brownish tint, presumably to marry them up to the colour properties of the archive footage. Worse still, the scenes of Padover in a US army jeep are deliberately edited into stock footage of a real American jeep driving into occupied Germany in 1945. Clever. But who was Christian Frey, a justly respected filmmaker, trying to fool?

Have our documentarymakers so lost their convictions and confidence that they believe they cannot hold the attention of their audience without these plonky, staged interludes, which demean the integrity of the real footage as much as they do the intelligence of the viewer? Of course, they can say that any movie of events before 1880 – whether the sand and sandals epics of the Roman empire or movies about Henry VIII or the latest BBC adaptation of War and Peace – has to be acted and recreated. But we acknowledge that these are totally imaginative recreations. Sometimes, they can include a tremendous emotional impact – rewatch the memorable A Man For All Seasons, for example, about the conflict between Henry VIII and his chancellor Thomas More – but we know that we are watching a filmed play, an attempt to show us what “might have been” rather than what was.

For history in the pre-photography age, documentaries use contemporary paintings – portraits of kings, queens, knights, battles – but we know that these are artistic constructions. The paintings may be realistic and some human faces may have a quality of almost photographic reproduction, even though there are no real photos by which this can be confirmed. But “recreated” scenes – still usually a clunker amid the real history – are clearly just that. In the post-photography age, however, re-enactments are now included without even a logo warning the viewer that these scenes are, in effect, artificial. The documentaries may be screening historical knowledge – but they are not evidential historical knowledge. The fraudulent “re-enactments” cancel out the truth of the archives.

But let’s return to the deliberate mix of real footage and real but generic footage. There is something promiscuous about all this. Historians, and reporters, are expected to cite their quotations correctly and date them accurately, not merge them with other people’s remarks made on different days or spoken in different countries. We do not expect to hear Churchill’s 1940 “This was their finest hour” speech mixed up with his iron curtain dialogue at Fulton Missouri in 1946 (though it is true that Goebbels was first to use the expression). Nor do we expect to read – as I did on a hard copy of a “historical” website the other day – that postwar Labour prime minister Clement Attlee (rather than Neville Chamberlain) concluded the prewar Munich agreement with Hitler in 1938. But pictures, even newspaper pictures, can be contaminated by the same virus as war documentaries.

An Imperial War Museum photo of a Second World War royal navy vessel escorting merchant ships has been variously captioned in British newspapers as taken in the Battle of the Atlantic and on the Arctic convoy route to the Soviet port of Murmansk. Not a hanging offence in photographic terms. But the ship cannot be in both oceans at once. Even The Independent, in its old print existence, was not immune. I still treasure a coloured photograph of a four-engined British Avro Lancaster bomber which appeared in an Independent book review on 20 August 2010. The photo, credited to Getty Images, was captioned: “Weight of war: loading bombs on to a Lancaster, 1940.” The problem was that the Lancaster only took to the air for the first time the following year – and did not start flying for bomber command until 1942.

Yes, mistakes can happen. But all this raises more serious mischief. The gold standard for Second World War documentaries remains Jeremy Isaacs’ awe-inspiring The World at War. Not only was the narration impeccable and accurate – Laurence Olivier would lend his name to nothing else – but the archive footage ran at great length, unedited and largely without musical accompaniment. Watch, for example, the sequence of the battle for Kohima in 1944. To observe the fighting and the wounded, carried under fire across miles of shell holes and burned trees, is profoundly moving, more so because only the original soundtrack of battle can be heard over minutes of raw black-and-white unedited film.

But the hidden dangers of mixed fake, “generic” and real footage are all too evident in the gloomy inheritance that any documentary of the 1915 Armenian genocide is heir to. In the aftermath of the First World War, many thousands of Armenian survivors sought to publicise their people’s destruction at the hands of the Ottoman Turks. Cheap black-and-white silent recreations of the murders, rape and starvation of Armenians were filmed, sometimes threaded with 1914-1918 archive material of the Turkish army and Armenian survivors. Real footage of Turkish troops in Istanbul was married to entirely acted sequences in which Armenian men dug their own graves and women were literally carried off by Turkish gendarmes and soldiers.

The events did actually happen. But once real footage of starving Armenian children was dropped into the film reels of fiction, three things happened: they lost the unstoppable power to convince, they muddled up the historical record – the acted sequences were produced less than 10 years after the genuine archive film – and they provided those who wish to deny the Armenian genocide the very means to do so.

Turkey now deploys an army of academics, “experts”, diplomats and journalists to claim that, while Armenians suffered “tragically” in the First World War, there was no plan or intent to murder, mass rape and torture to death the one-and-a-half-million victims. Brave Turkish historians like Taner Akcam have proved that such plans did exist. This was the greatest war crime of the First World War – far exceeding the German mass murder of civilians in Belgium in 1914 – but Armenia’s understandably ferocious but pitiful post-genocide films have muddled the real and the re-enacted scenes of this terrible crime.

The 1919 American-produced silent black-and-white movie Ravished Armenia (it was also titled Auction of Souls), for example, was based on the experience of real-life genocide survivor Aurora Mardiganian, who had gone through her own terrifying ordeal only four years earlier. It combined both documentary and re-enacted scenes. The latter included the crucifixion of Armenian women.

Turks have often pointed out to me that this “recreation” totally disqualifies the film’s content, a claim that was not helped when Mardiganian herself recalled many years later that the crucifixion scenes were wrongly portrayed. In reality – “real” reality, that is – the error in the film, according to Mardiganian, was that the young women were not crucified but sexually impaled on stakes. No matter. The Turks made their point.

Somehow, we’ve got to break the assumption that we can slide old footage together without caring about the sanctity of the historical record. Or mixing in essentially fake scenes – filmed to “fit in” with the footage – on the vague premise that the audience will understand this collage

That films were already an important means of Armenian truth-telling was evident in 1935, when the Turkish government put pressure on the US State Department to persuade MGM to abandon an ambitious feature film on the heroic Armenian defenders of a Turkish coastal town in 1915, The Forty Days of Musa Dagh. Clark Gable was to have starred in the movie. MGM scrapped the film. More recently, Armenians and Turks both produced their own feature films of the genocide, The Promise and the The Ottoman Lieutenant (which naturally mentioned no genocide at all). The Promise was the winner.

But the real “proof” of the genocide lies in original, non-recreated footage. Over the years I have tried to trace contemporary film of the Armenian massacres which has never previously been seen – or at least, not seen since the first days after it was developed. I have found several hundred feet of film of Armenian refugees rescued by the Americans at Smyrna in 1922 – another story, but it was part of the ragged end of the genocide – and discovered a photograph of a Great War film cameraman taking footage of the return of Armenian survivors under French protection to the ruins of their homes in Turkish Anatolia. I am still searching for the forgotten repository or archive where his work might still lie unseen. There is a rumour – which I hear frequently – that Kurdish militiamen who, alas, played an important role in the massacre of the Armenians took their own film of newly murdered Armenians in 1915 to show off their handiwork to the Ottoman Turkish authorities. It is not impossible. Primitive movie cameras were state-of-the-art science at the time; Germans in wartime alliance with the Ottomans certainly brought them to Turkey. But I have been unable to discover any such material.

Somehow, we’ve got to break the assumption that we can slide old footage together without caring about the sanctity of the historical record. Or mixing in essentially fake scenes – filmed to “fit in” with the footage – on the vague premise that the audience, especially younger viewers for whom the world wars are generations removed, will understand this collage. Or not, as the case may be.

For what of future generations? In a hundred years’ time or two hundred years’ time will students, researchers, historians or cinemagoers really make any difference between 1914 and 1916 or between the blitz and Operation Barbarossa – or between real people and actors? Histories of the Armenian genocide have so often blurred the difference between earlier photographs of the 1890s Hamidian pogrom of Armenians and the 1915 butchery, especially photos of corpses and hangings, that even though I know these individual and original pictures very well, I find myself increasingly confused each time I see them. In my mind, you see, they have already become “generic”. I have myself started to accept the misuse of the evidence.

That’s what it is all about. For once you don’t care about historical accuracy, you stop caring about history. The moment a bomb in Britain is the same as a bomb in Russia or one bloodbath is the same as another bloodbath or when a bunch of actors try to mimic the truth of war, then our archives lose their meaning.

Politicians, of course, have no objections. Fake film and fake history have a lot in common. Saddam or Assad or Ahmadinejad can be recreated in our minds as Hitler, Nasser can be equated with Mussolini, our own brave leaders can pose as Churchill or Roosevelt. Amid this nonsense, Blair could tell us in 2003 that America stood with Britain after the fall of France in 1940. Untrue. The US was neutral until December of 1941. Then he told us that America was Britain’s oldest ally. Untrue. Our oldest ally is Portugal. Hands up who knows who first deployed gas in the Middle East? Saddam? Nasser? No. It was General Allenby in the First World War, when he used gas against the Ottoman Turks – in Gaza! If we can blur the pictures of history, we can blur history itself.

Archives are for all. There must be no “historians-only” rules. They belong to us. But the care of these precious original resources must be as jealously guarded – and protected – as medieval parchments and Renaissance paintings.

The distortions may begin with a big gun that fires too many times in too many places – or with wrongly coloured toy trains. But it needs more than a five year old to spot the difference.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News