A skeleton: it does not blush

When I was eight, my mother made a Halloween costume for me for a party I was going to. Even at eight, this seemed like an important party. The costume was beautiful, as the things my mother made often were: more beautiful than a child’s thing ought to be, more beautiful than a mother ought to be able to make after work.

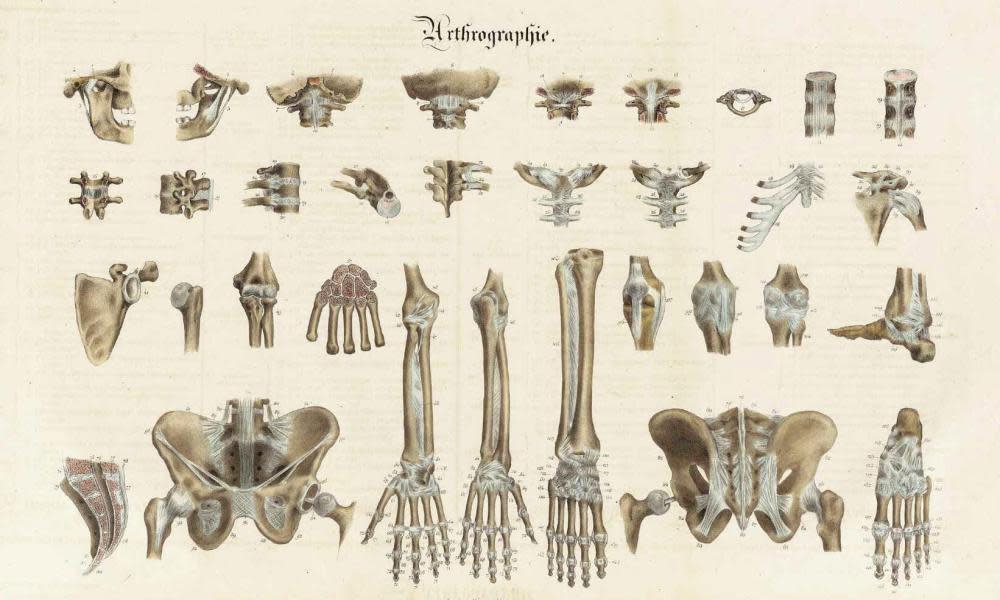

It was a skeleton costume: a unitard made from stocking fabric, painted with fluorescent paint; I remember the care she took to make the bones accurate, to make them just my size, matching femur to femur.

But when I arrived in the late afternoon – the importance of the party had a lot to do with the fact that it would continue into the night-time – one of the boys in my class realised that the costume was transparent. It soon got dark and the black fabric turned opaque and the bones began to glow.

Related: An egg: unfertilised, it is one giant cell | Helen Sullivan

Then, I did something wrong during “wink murder”, something that gave the game away, and I felt embarrassed a second time. It is a good thing skeletons can’t blush.

Recently, a skeleton expert wrote to me. He has studied bone biology for 35 years, and he explained that the skeleton has the “ability to adapt its mass and architecture to provide enough strength for habitual functions with a reserve in order to prevent fracture under unusual/unforeseen loads.”

The skeleton does not blush: it is our reserve, it outlasts us, it is stronger than all it protects. This should be comforting, but it is unsettling.

“He knew the anguish of the marrow / The ague of the skeleton; / No contact possible to flesh / Allayed the fever of the bone,” TS Eliot writes in Whispers of Immortality.

When I think of a skeleton, I think of a skeleton family: putting my ear next to my father’s knee, which creaked and scratched from a cricket injury. My double-jointed sister digging her fingers in under her ribcage above her abdomen and bending the cartilage outwards. The skeleton family in Funnybones: “The white, white Dog disappears in the white, white snow and the black, black Cat disappears in the dark, dark shadows.”

At university, I learned fencing. Recently, 15 years since I last picked up a foil – the long, thin, bendy sword – I happened to be near a group of fencers. I felt my marrow ache and flash: I wanted to duel. In fencing, you wear a white costume, you turn yourself into a skeleton, advancing and retreating, elegant and clean. I had forgotten the feeling of the foil poking you; that the point of fencing was to remind your opponent of their nerves and skin, of their fallibility, and at that moment, of their having lost.

The first time I tried fencing, I thought I looked fantastic. Afterwards, I made my way home: a long bus journey, in winter. An hour later, I saw my bright red face for the first time: a face boiled in a mask. I looked like a fool.

Related: A sea snake: like a nightmare generated by a sleep app | Helen Sullivan

What to make of this experience? I remember that I waited for the bus with a friend of mine, and that she was studying linguistics. She showed me some of her exercises: they were about how one sentence could mean many things.

For 15 years, this memory has been rolling around my brain, protected by a skull, the skeleton expert tells me, which “has to be deformed by around 40 times its normal deformation before it is broken”. It is only now that I realise that the skeleton does not blush, but its marrow makes the blood that rushes to the surface. It is only now that I realise this: that words are skeletons. They provide enough strength for habitual functions and for so much more: both unusual and unforeseen.

• Helen Sullivan is a Guardian journalist. Her first book, a memoir called Freak of Nature, will be published in 2024

• Thank you to Professor Tim Skerry for suggesting the topic for this week’s column – and for the insights into the human skeleton. Have an animal, insect or other subject you feel is worthy of appearing in this very serious column? Email helen.sullivan@theguardian.com

Yahoo News

Yahoo News