The solution to the problem of business rates is obvious – base them on land value

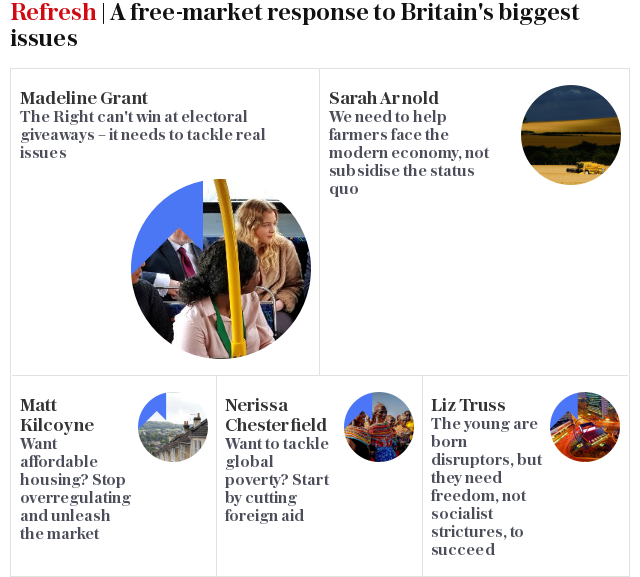

Welcome to Refresh – a series of comment pieces by young people, for young people, looking for a response to Britain's biggest issues

Louis XIVs Finance Minister Jean-Baptiste Colbert once described the art of taxation as “plucking the goose as to obtain the largest possible amount of feathers with the smallest possible amount of hissing”. On that measure, business rates must be the most painful method of goose plucking ever envisioned.

Few taxes attract more ire. When we surveyed 491 business-owners for the All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) for Entrepreneurship, over half thought that business rates were damaging to entrepreneurship in the UK (more than for any other tax).

Business rates do need reform, but it’s important to correct a common misconception.

Economists distinguish between legal and economic incidence. In layman’s terms, who signs the cheque to HMRC isn’t always the one who pays. Take the Soft Drinks Industry Levy, the manufacturer may pay the taxman, but it’s those who consume Coke and Pepsi that bear the burden through higher prices.

Any attempt to level the playing field between Amazon and the high street by cutting rates would fall flat

When it comes to business rates, economists believe that it's the landlords and not businesses who really pay. The logic runs as follows. Most goods are determined by a mix of supply and demand. But when the supply of a good is fixed, then the price is determined by demand.

Because the supply of commercial real estate is relatively fixed due to restrictive planning controls, the price of occupancy (rates plus rents) is determined by the highest amount a company is willing to pay.

Businesses are still only willing to pay so much to occupy a premise, so when rates rise, landlords simply can’t charge rents as high as before.

The theory’s backed up by solid data. Research from the British Property Federation found that in response to a rate rise, rents would fall by around 75 per cent of the initial rate rise after around three years. In the long-run, landlords, not businesses, pay.

Any attempt to level the playing field between Amazon and the high street by cutting rates would fall flat. Serving little purpose other than to pad the pockets of commercial landlords.

However, the three-year transition is painful and the public most likely wouldn’t buy the argument that landlords are the ones really coughing up.

It’s not helped either by the fact that incorrect valuations are not uncommon, while the appeals process is costly and bureaucratic.

It’s as if business rates were designed to be as unpopular as possible.

While business rates often attract unfair criticism, there is still a strong case for reforming them. They’re a half-good, half-bad tax.

A restaurant that installs a walk-in fridge or a shop that installs CCTV will be rewarded with a hefty tax bill

Half-good because it’s partially a tax on land, which is in fixed supply and is probably the most efficient way to raise tax out there. Half-bad because it taxes property improvements – a restaurant that installs a walk-in fridge or a shop that installs CCTV will be rewarded with a hefty tax bill. Manufacturers are hit hard by rate increases when they invest in blast furnaces, building berths or backup generators.

The solution should be obvious. Scrap the half-bad part. If business rates were instead assessed solely on land values, landlords would no longer be discouraged from renovating and improving their properties. By breaking down a barrier to investment, this reform would boost output, raise wages, and create jobs.

In addition to that, shifting the legal burden from businesses to commercial landowners should be a no-brainer.

Painful transitions would be unnecessary as companies would no longer be forced to get by while rents adjusted.

It would shred paperwork for business since most would never have to pay rates or appeal incorrect valuations. Under the status quo, fifty or more separate tax bills could have been filed from the same co-working space. If the legal burden was shifted, only one would be necessary.

Tax reform is often more popular in theory than in practice, but fixing business rates would boost growth and win votes.

Sam Dumitriu is Head of Research at the Adam Smith Institute

For more from Refresh, including debates, videos and events, join our Facebook group and follow us on Twitter @TeleRefresh

Refresh | |

Facebook Group · 475 members | |

Join Group |

______________________________________________________ What is Refresh? Refresh is a policy discussion forum with the express aim of reinvigorating s...

Yahoo News

Yahoo News