Space telescope picks out 800 new 'invisible' galaxies

An infrared telescope in Hawaii has caught a glimpse of 'invisible' galaxies - young, distant galaxies that are among the brightest in the universe.

An infrared telescope in Hawaii has caught a glimpse of 800 'invisible' galaxies - young, distant galaxies that are actually among the brightest in the universe.

Although they are invisible to the naked eye, due to being shrouded in dust, the galaxies are burning far brighter than our own - although some are 12 billion light years away.

They would outshine our own Milky Way by hundreds, perhaps thousands of times.

A combined survey using the Herschel space telescope and the Keck telescopes at the Mauna Kea observatory in Hawaii pinpointed 800 such galaxies.

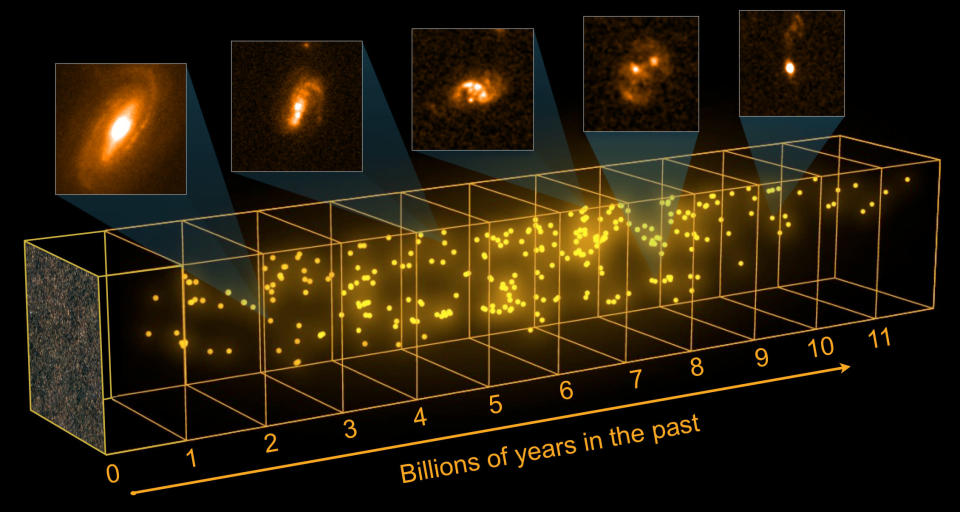

Because of the time it takes light to travel to Earth, we see some of these galaxies as they were close to the dawn of time, 12 billion years ago. The find could help scientists unravel how galaxies form.

[Related: Voyager probe 'at edge' of our solar system]

They are forming stars so quickly that between 100 and 500 new stars are born in each galaxy every year, and have been coined “starbursts” by astronomers.

While it’s not clear what gives these galaxies their intense luminosity, it could be the result of a collision between two spiral-type galaxies, similar to the Milky Way and Andromeda galaxies.

Or they could be in a particularly gas-rich region of space, where galaxies form stars quickly due to constant bombardment from gas and dust.

Dr. Caitlin Casey, a Hubble fellow at the UH Manoa Institute for Astronomy said, “Herschel is an infrared space telescope sensitive to wavelengths not observable from within Earth’s atmosphere."

“Detecting these bright infrared galaxies used to be difficult, and a handful was plenty; now with Herschel we are finding them by the thousands, enabling a census like this,” said Göran Pilbratt, European Space Agency Herschel Project Scientist.

Once found, taking measurements of these galaxies at visible wavelengths required using the 10-meter Keck telescopes, the two largest optical telescopes in the world.

Over the course of several nights the group was able to detect and measure distances to nearly 800 of these galaxies.

“For the first time, we have been able to measure distances, star formation rates, and temperatures for a brand new set of 767 previously unidentified galaxies,” said Dr. Scott Chapman, a co-author on the studies. “The previous similar survey of distant infrared starbursts only covered 73 galaxies. This is a huge improvement.”

“While some of the galaxies are nearby, most are very distant; we even found galaxies that are so far that their light has taken 12 billion years to travel here, so we are seeing them when the universe was only a ninth of its current age,” Casey said. “Now that we have a pretty good idea of how important this type of galaxy is in forming huge numbers of stars in the universe, the next step is to figure out why and how they formed.”

“It’s hard to figure out how most galaxies formed based on information from only a small part of the universe, just like it’s hard to guess how big an elephant is if you only get a glimpse of its tail,” Casey said.

“Now that we have an accurate census of starbursting galaxies across a huge time period in the universe’s history, we can start to piece together how these galaxies grew and evolved.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News