We Need to Talk About Cosby review – shocking revelations going right back to the 60s

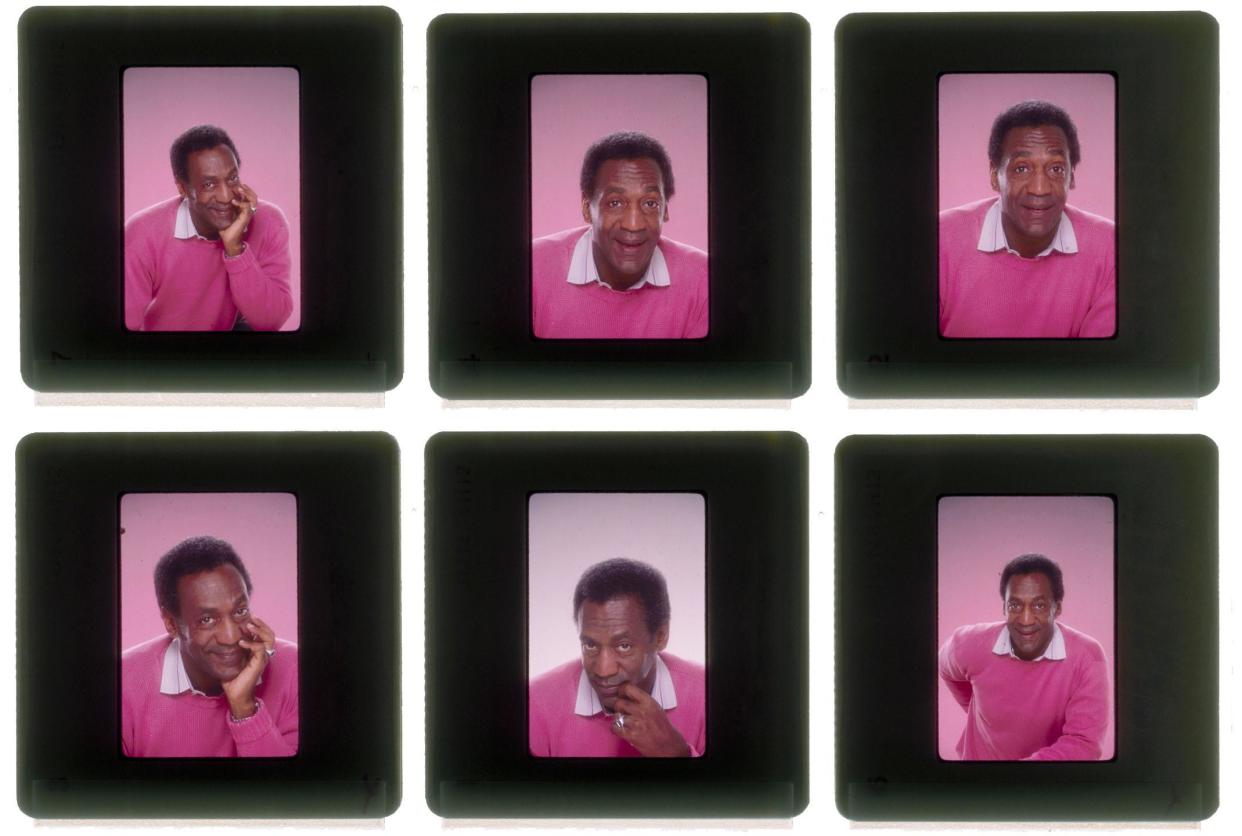

‘Who is Bill Cosby now?” is the question that opens comedian, author and TV presenter W Kamau Bell’s four-part documentary about his fallen idol, We Need to Talk About Cosby. “America’s Dad” is one moniker, offered by an interviewee with a thousand-yard stare. “An example of the complexity of humanity,” suggests another. “A rapist who had a really big TV show once,” says Renée Graham, columnist and associate editor of the Boston Globe.

In the first episode of this exploration of Cosby’s career, alleged (pending an appeal against the overturning of his 2018 convictions for aggravated sexual assaults) multiple predations against women for decades, and the meaning of both for Black Americans, especially, Bell interrogates all three assessments of the man.

By insisting that only Black stuntmen double for him, he ended the practice of white stuntmen painting themselves black

It is an avowedly personal project. As a Black man and standup comic born in the 70s, says Bell at the outset, “I am a child of Bill Cosby.” He outlines Cosby’s meteoric rise – it took him no time to go from student bartender cracking jokes to guest on The Jack Parr Program and from there to television star (as the erudite joint lead of the weekly drama I Spy) and mainstream, crowd-pleasing comedian winning multiple Grammys for his annual albums. And he contextualises what it meant for Black people to see this charming, urbane, handsome and talented man publicly give the lie to so many racist myths that permeated the culture even more than they do 50 years on. Cosby brought about more tangible changes, too. By insisting that only Black stuntmen be used to double for him in I Spy, he ended the practice of white stuntmen literally painting themselves black and created a new avenue of employment for Black men in the industry.

But, just as you start to think this is going to be another rise-and-fall-of-a-once-great-man outing that only just avoids hagiography, Bell performs a screeching U-turn. He doubles back to the beginning of Cosby’s career and brings out of the shadows allegations of drugging and assault going right back to 1965. The good he did, symbolically and practically, is shown to run concurrently with (alleged) great harms. His friendship with Hugh Hefner (a supporter of the civil rights movement) and the condoning of any number of male behaviours in an essentially misogynistic system and era are reviewed. As is Cosby’s famous Spanish fly routine on his 1969 album It’s True! It’s True!, about how it only takes a tiny bit of the famed aphrodisiac to render a woman insensible.

Kierna Mayo, former editor-in-chief of Ebony magazine, says it is like he was laying a trail of breadcrumbs for someone to track. She attributes it to a guilty conscience. Others – especially those reminded of Jimmy Savile’s many mentions of liking underage girls and his “my case comes up next Tuesday” quips – might be more inclined to suspect just another manifestation of the malignant arrogance and narcissism serial predators frequently possess. Hiding in plain sight is so much more thrilling than simply hiding.

There is a full testimony from Victoria Valentino, one of more than 60 women who have come forward to accuse America’s Dad of rape and other abuses, about how Cosby drugged her and her friend, and raped Valentino in 1969. It was a few weeks after her six-year-old son Tony had drowned in a swimming pool. She told virtually no one for 45 years. The only time tears threaten to overwhelm her is when she recalls how, when she asked afterwards how she would get home, and, without looking back at her, Cosby gestured at a phone and told her to call a cab, “I said thank you.”

So, Bell adds another question to his pile – how much of Cosby’s good work was a deliberate smokescreen to allow his monstrous side to go undetected and its victims unbelieved? Again, the parallels with charity-fundraising, hospital-visiting Savile are striking.

Only the first episode was available for review, but We Need to Talk About Cosby so far promises to be an exhaustive examination of the subject. Just possibly slightly exhausting too – I’m not sure we need a pharmacologist to explain the actual chemistry and effects of Spanish fly – but if so, it will be a minor flaw born of Bell’s willingness to anatomise everything he comes across. It is clearly a heartfelt film, but not blinkered, and while his personality suffuses the whole, he makes sure to get out of the way of the women telling their stories and lets them own the screen for as long as they need. That, and the insistence on showing the co-existence of the man and the apparent monster, make this a showcase for the way we need to talk about all the Cosbys out there. Allegedly.

We Need to Talk About Cosby was shown on BBC Two and is now on iPlayer in the UK, and is streaming on Paramount+ in Australia

Yahoo News

Yahoo News