The way we respond to being stared at may reveal how much power we think we have

Niki K

When someone looks you square in the eye, is your first instinct to look away or meet their gaze?

In a blog post for Psychology Today, Audrey Nelson discusses how continuous eye contact for ten seconds or longer is disconcerting. It can make the recipient feel like they have something in their teeth, or that they are being challenged.

However, it doesn't have to be prolonged eye contact for some people to feel uncomfortable. Certain individuals just don't like looking into other people's eyes. Those with autism, for example, can find looking someone in the eyes incredibly stressful.

This doesn't mean that everyone who dislikes eye contact is on the autistic spectrum, though. According to research discussed in another blog post in Psychology Today, avoiding someone's gaze could also be an evolutionary behaviour we have picked up to respond to threats. If someone is staring at us and we feel uncomfortable, we might start thinking we are of a lower status, or they are trying to intimidate us.

New research led by Mario Weick, a psychology professor at the University of Kent, sought to find out whether a person's sense of power affected their responses to displays of dominance, like staring. The results were published in the journal Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin.

Subjects took part in two studies. In the first, 80 people were randomly split up in to low-power, neutral, and high-power groups. Then the researchers used "mind-set priming" where they asked the participants to write about a past event where they felt disempowered, neutral, or powerful relative to the group they were put in.

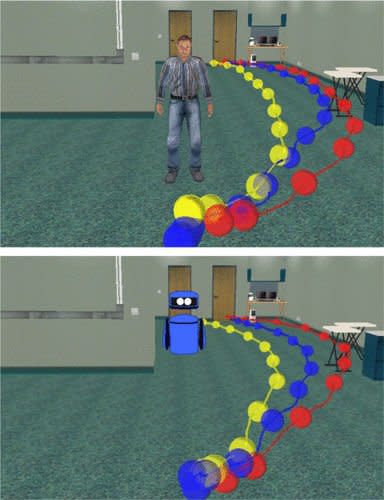

Weick et alThey were then placed in a virtual world using a VR headset, and told to walk around a target. They were asked to do this twice — once walking around a robot and once walking around a person.

Weick and the team found that participants who had written about feeling powerful were more likely to approach targets that looked directly at them than those who had written about neutral power or feeling powerless.

This only happened when the target looked like a human, though, as there was no significant difference between how the groups approached the robot.

The two targets displayed different gaze behaviours. They either made a head movement turning towards the participants and persistently gazed at the subjects, or did not move and apparently ignored the subjects. The results only showed a difference in how the participants approached the targets when they were staring at them.

"Social motives may underpin the effects of power," the paper reads. "In particular, the differential responses to the human target may be triggered by an implicit desire to signal hierarchical relations to conspecifics."

In other words, the difference in how people reacted to the human staring them down might have been related to where we have placed ourselves in the hierarchy of our species, such as what social status we have.

In a second study, the researchers added more variables to the experiment, such as another setting where the human and robot targets looked away from the participants as well as gazing ahead or staring at them. Targets also differed in heights.

The results showed that out of 103 student participants, those who perceived the targets as shorter than themselves were more likely to approach them even if — and especially if — eye contact was maintained. This seemed to suggest that targets were seen as less intimidating if they were shorter, regardless of whether they were staring you down.

Whether you stare someone down or look away is probably a reflex that you can't change.

A study from 2011, published in the journal Psychological Science, looked into how staring for dominance is automatic for humans, because it's how our evolutionary ancestors earned their places in their social hierarchies.

The researchers asked participants to complete a questionnaire that reflected how dominant they were in social situations. Then they tested how long it took them to look away from faces on a screen with different emotions — angry, happy, or neutral.

People who were more dominant took longer to look away from angry faces, whereas those who were more motivated to seek rewards looked at the happier faces longer. The researchers said this suggests we are wired one way or the other.

"When people are dominant, they are dominant in a snap of a second," says David Terburg, author of the study, in a statement. "From an evolutionary point of view, it's understandable — if you have a dominance motive, you can't have the reflex to look away from angry people; then you have already lost the gaze contest."

See Also:

Police say the final Grenfell Tower death toll won't be known until next year

Victims of the global cyberattack have paid $9,000 so far but can't get their files back

SEE ALSO: New research on the biology behind over-thinking shows how it makes us less creative

Yahoo News

Yahoo News