Why it’s time to take the Liberal Democrats seriously again

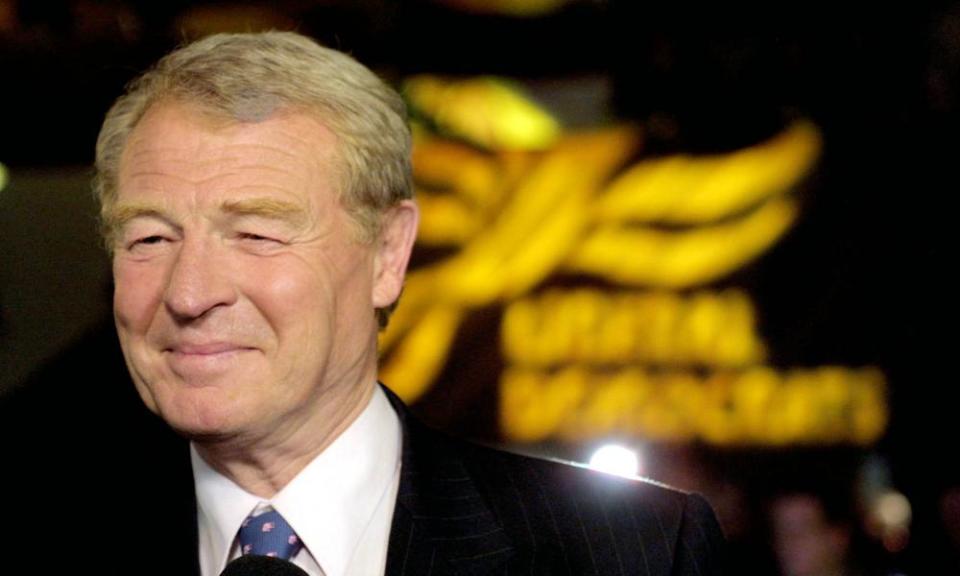

Beneath the soaring arches of Westminster Abbey at Paddy Ashdown’s memorial service on Tuesday, it was sometimes tempting to imagine Britain’s liberal tradition regaining something of its former eminence. As the service came to an end, and with a theatricality fully worthy of the former Liberal Democrat leader himself, a valedictory Last Post was followed by a summons to action in the Reveille. A sense of resumed purpose was unmistakable in the sunlit chatter outside the abbey.

Related: The Lib Dems’ plan to revoke article 50 is as undemocratic as the race to no deal | Stephen Kinnock

The Liberal Democrats have been marginalised by most commentators for many years. It is easy to see why. Tarnished in leftwing eyes by austerity and in rightwing ones by pro-Europeanism, the post-coalition electoral implosion of 2015 reduced the party from 57 Commons seats to a mere eight. Fewer people voted Lib Dem in the 2017 election than for the Lib Dems or their predecessors in any election since 1970.

All that has now changed. Today, there are powerful reasons for taking the Lib Dems seriously again. Some of the reasons are simple electoral realities. In the English local elections in May, the Lib Dems harvested more than 700 new council seats. In the European elections, a 13% swing raised them to second place, helping to knock Labour into third and the Conservatives into fifth. Opinion polls now consistently show the Lib Dems in the upper teens, running Labour close in the race for second place. In Britain’s new four-party battle (five in Scotland and Wales), the Lib Dems are indisputably a prime player once more.

In an echo of former glories, the party recaptured Brecon and Radnorshire in a byelection last month. If there is a byelection in Sheffield Hallam, they might retake that, too. In Scotland two weeks ago, they saw off the SNP’s attempt to capture the Shetland seat in the Holyrood parliament. At Westminster, three former Labour MPs and two former Conservatives have joined the Lib Dems. Others may follow, especially if parliament returns early. Party membership, at more than 120,000, is now at a record level. When the Lib Dems gather in Bournemouth on Saturday for their autumn conference, the new leader, Jo Swinson, may not tell them to prepare for government, but she can certainly tell them they are right there in the contest.

This Lib Dem revival rests on political foundations that are different from earlier ones. Brexit is pre-eminently the most important. The Lib Dems have set out to be the party of the 48%. Their recovery went hand-in-hand with growing support for a second referendum. This week they signalled they will campaign to revoke article 50 altogether. As the Conservatives have moved towards ever harder Brexit positions, and as Labour continues to send out mixed Brexit messages, the Lib Dems have reclaimed the right to be heard – not least among young voters – that they lost in 2015.

The Lib Dems are also winning support on social and economic policy. The statist instincts of Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour and the deregulatory dogma of Boris Johnson’s Conservative party have combined to leave the Lib Dems as Britain’s principal party of the mixed economy. Labour’s programme may in fact be more social democratic than socialist, and Johnson himself is not as much of a laissez-faire liberal as most of those on the Tory right. Yet in our ever more sharply polarised party system, the Lib Dems are currently almost unchallenged as the party of the middle ground.

The Lib Dems have prospered as the remain party. But this concentration involves risks as well as rewards. One risk is that Swinson’s support for revocation may strengthen the party’s core remain vote, but simultaneously alienate remain voters who still seek a negotiated exit. Another is that the party could be left high and dry, in the middle of an election campaign, by events. As one party notable put it to me outside Westminster Abbey: “What do we stand for if the UK has left on 31 October?” In the short term, there is probably enough remainer anger in the country to keep the Lib Dem vote intact in an early election. In the following months, though, the party will have to decide where it stands on rejoining the EU. The danger of being the party of a lost cause is real.

All of this ought to make the Bournemouth conference focus rather more on defining the kind of political economy for which the Liberal Democrats now stand. This is an age-old question. But it came to a 21st-century head in the pro-market Orange Book in 2004 and the embrace of austerity and public spending cuts after 2010. Politics and the public mood have moved on. Even the Conservatives now pronounce the end of austerity. But there is scant evidence yet that the Lib Dems, who remain defensive about their role in government, have moved decisively with the new times.

To be fair, this is a question that faces an entire generation of political parties and voters in every advanced industrial democracy, not just Britain. It is also one that few modern parties of the centre have succeeded in solving. The Lib Dems are certainly not alone in struggling with it. Yet it holds the key not just to the party’s philosophical underpinning, but to some very practical political choices, too.

Related: 'A man for ideals': former PMs pay tribute to Paddy Ashdown

Swinson’s party will only consolidate its comeback by electing more Lib Dem MPs. Under Britain’s first-past-the-post system, that will only happen if there is the kind of tactical voting in the next general election that helped Ashdown to more than double the number of Lib Dem MPs in 1997. Ashdown succeeded because sufficient numbers of progressive voters recognised that he led a party that could work with Tony Blair’s Labour. Swinson, by contrast, faces a much more difficult relationship with a Labour leadership from which many Lib Dem supporters recoil. Yet unless she can make that relationship work, there will be only one winner, and it will not be the Lib Dems.

• Martin Kettle is a Guardian columnist

Yahoo News

Yahoo News