Climate protest accused defies judge to give hours-long speech in court

A climate protester ignored a judge’s instructions and refused to leave the witness box, instead delivering an hours-long speech telling jurors that his alleged role in a conspiracy to block the M25 was justified by the risk of human extinction.

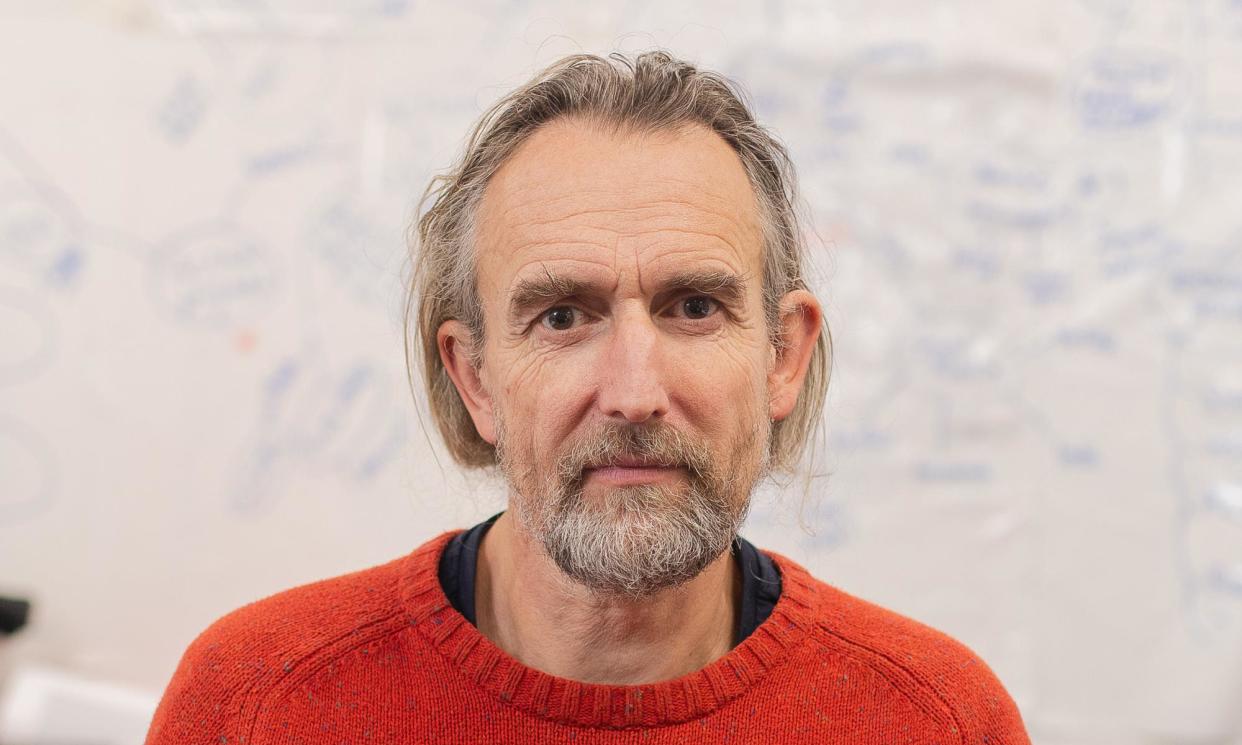

Roger Hallam, 58, spoke for more than two hours on why a judge was wrong to rule that he and co-defendants could not bring evidence in their defence on the impacts of climate breakdown, and why such evidence justified the sort of acts of which they are accused.

The judge Christopher Hehir sent out the jury three times during Hallam’s extended address, left the court himself once, and interrupted Hallam many times to make clear it was not his place to instruct jurors on points of law.

But Hehir eventually let Hallam continue, to the defendant’s apparent surprise. “I apologise to you if I’m a little bit incoherent,” Hallam told jurors towards the end of his address. “I didn’t actually expect that I was going to get this far.”

Hallam is on trial alongside Louise Lancaster, Daniel Shaw, Cressida Gethin and Lucia Whittaker-de-Abreu on a charge of conspiracy to cause a public nuisance for allegedly organising activists to climb gantries on the M25 over four days in November 2022.

Hallam, the first of the five to give evidence in their own defence, began by denying his part in the alleged conspiracy. He was directed by Hehir to address part of the prosecution’s evidence, a recording of a Zoom meeting addressed by the defendants apparently to recruit activists to take part in the M25 campaign.

“I wish to say on oath that I was not involved in this campaign,” Hallam told the court. “I was never sent any information about the campaign. I was never invited to meetings about the organisation of this campaign. I have no knowledge of the details of the campaign. I was asked to come and do a talk, and the talk was introduced as giving the case for civil disobedience.”

Hallam said he had given hundreds of such talks. “On all the other occasions I have given a speech on this subject I have never been subject to prosecution,” he said.

“My point is, making an argument in public, making an argument that something should happen and advising people that in my opinion they should engage in civil disobedience, is self-evidently in and of itself not a conspiracy … it has to be supplemented by other evidence.”

Hallam then embarked on a lengthy discussion of the law around public nuisance and the defences that he believed he and his co-defendants were entitled to.

Hehir repeatedly interrupted Hallam. “I’m not going to permit you to lecture the jury, wrongly or rightly, about the law,” he said.

Hehir had ruled that the defendants could not bring extensive evidence about the impacts of climate breakdown but that they could speak about their political or philosophical beliefs on the issue, to give context to actions.

Hallam’s speech led Hehir to send the jury out of the courtroom three times. Hehir told jurors they were to take instructions on the law only from him and that Hallam’s evidence about the impacts of climate change was not relevant.

“I already ruled in your absence that the jury can’t be presented with further evidence about climate change,” the judge told jurors. “Each defendant is entitled to say something about their own beliefs about climate change.”

Hallam said: “There is a not insubstantial possibility of absolute human extinction by putting greenhouse gases into the atmosphere at this moment in history. What we are looking at here is no one existing any more because everyone has died in the most excruciating awful circumstances.”

The trial continues.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News