Sir Michael Parkinson obituary

There was a time – several decades, actually – when Sir Michael Parkinson, who has died aged 88 after a brief illness, was one of the most ubiquitous figures on national television. He was not the first to host a chatshow but he was the most durable and versatile, largely because he saw himself as a journalist rather than a broadcasting personality.

He was also able to present a variety of programmes on both radio and television, and write insightful weekly columns, mainly about the sports he loved – primarily cricket – for a succession of national newspapers.

With his wry, confiding demeanour and his characteristic facial twitchiness, asking polite but occasionally convoluted questions in his soft Yorkshire accent, often while fiddling self-consciously with his hair or scratching his nose, he interviewed more than 2,000 guests over 20 years, ranging from Hollywood actors to favoured sports stars, actors and comedians, and occasionally literary and intellectual figures, on his eponymous show.

It aired first on the BBC between 1971 and 1982, then again between 1998 and 2004 when the programme was revived, and finally for a further three years on ITV until 2007, after they fell out over a revised contract.

Interviews could be serious, or anecdotal, but the emphasis was always on the guest, not the presenter: thus Alistair Cooke, the mathematician Jacob Bronowski, WH Auden, Jonathan Miller, Henry Kissinger and the Salvation Army pioneer Catherine Bramwell-Booth (born in 1883) made appearances, as well as the more usual fare of show business personalities. Parkinson was well briefed and rarely fazed by any of them.

When asked why he had often asked deferential, even star-struck questions, Parkinson – known as Parky – insisted in a Telegraph interview: “The people I interview aren’t criminals or child molesters, so why on earth should I act like an interrogator? I relax the guests, I am a great listener.” He told the Guardian: “I am the boss, not them. It’s my patch, not theirs. This is my home … they have got to come down my stairs into my living room and talk to me.”

He had Jimmy Savile and Rolf Harris on the show long before their crimes came to light, but he did probe Woody Allen about his relationship with his stepdaughter shortly before he married her. On occasion he could ask excruciating questions, such as to Helen Mirren during a show in the 1970s about her “physical attributes” – to which the actor reacted with dusty incredulity, years later describing him as a “sexist old fart”. In his defence Parky said that he wasn’t sexist, he was “Yorkshire”.

The programme was a broadcast version of a newspaper journalist’s interview, except with a studio audience and a band just out of shot. “The graveyard is full of people who tried talkshows and didn’t make it, mainly because they weren’t journalists,” he told the Guardian in 2012. “No talkshow presenter these days asks questions and listens to the answers.”

He was lucky to catch some of the great figures of the movies he had watched as a child at the local cinema in the 40s: Orson Welles (his first guest), James Stewart, Fred Astaire, James Cagney, Shirley Temple and Bette Davis – figures too venerable or polite to be obstreperous. But there were moments in later shows when interviewees refused to perform: a drunken Robert Mitchum answering monosyllabically, a disdainful Meg Ryan advising him to wrap up an interview that was not getting anywhere.

And, of course, the comedian Rod Hull’s emu puppet, which launched an unprovoked attack in 1976 and wrestled Parkinson to the ground. “The only thing I’ll ever be remembered for,” he later complained, “is being attacked by a fucking emu.”

Over the years there were precious few stars who did not appear on the show. It took 20 years to get Madonna to come on, but eventually she did. Billy Connolly got his national show business break on the show after a taxi driver advised Parkinson about his comic potential. John Lennon refused to answer questions about the Beatles unless Parkinson asked them in a sack and he duly clambered into a bin bag to do so.

Sometimes the show produced more than well-rehearsed stories, as when Eric Morecambe described his first heart attack or Victoria Beckham confided that her name for her footballing husband was Golden Balls.

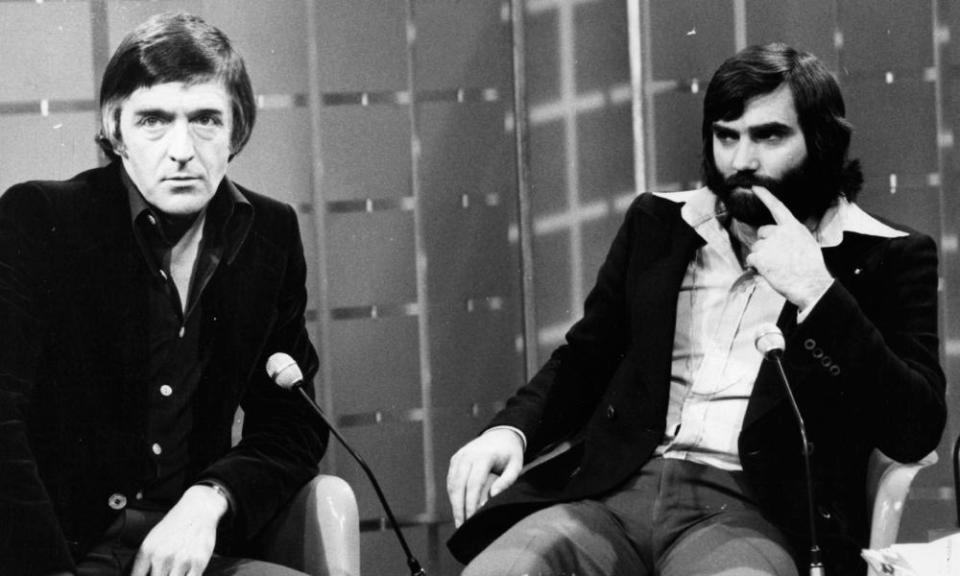

There were sports stars too, cricketers such as Parkinson’s friend Geoffrey Boycott railing at the way he had been treated by Yorkshire, Bobby Charlton and a drunken George Best and, four times, Muhammad Ali, who belligerently told him on one occasion: “You do not have enough wisdom to corner me on television. You are too small mentally to tackle me,” while looking as if he was about to punch Parkinson’s lights out.

Their friendship mellowed later and Parkinson said after the boxer’s death that he was the most amazing man he had ever met.

Born in Cudworth, near Barnsley, South Yorkshire, Michael was the only child of Jack Parkinson, a miner at Grimethorpe colliery, and his wife, Freda (nee Dawson), who determinedly encouraged her son to read and took him to the cinema four times a week. He described her as the engine of his ambition. “She opened up the prospect of a life beyond the confines of a pit village,” he said later. From his home on a council estate he won a scholarship to Barnsley grammar school. Just to make sure he never ended up down the pit, his father took him into the mine as a boy to show what working conditions underground were really like.

What his father did bequeath him, though, was a lifelong love of cricket – and he was an accomplished club cricketer, too, playing on level terms for Barnsley in the Yorkshire league with the young Boycott and the future test umpire Dickie Bird. He claimed to have had a trial for Hampshire while serving locally during national service, only to be dissuaded by his father with the words: “It’s not like playing for Yorkshire, is it?”

Parkinson left school at 16 with just two O-levels – English and art – and became a trainee reporter on the South Yorkshire Times, covering flower shows, magistrates courts and local Women’s Institute meetings, to which he pedalled on the office bike, before moving up to larger local papers.

His national service coincided with the Suez crisis, where he found himself appointed as a press liaison officer – promoted at the age of 20 to be one of the youngest captains in the British army – to shepherd reporters covering the Anglo-French invasion. “I wanted to be them. It was no good going home and covering local bingo winners,” he wrote later.

Back in Yorkshire, he was recommended to the Manchester Guardian by Dick West, one of the paper’s reporters who had fallen asleep the worse for wear at a meeting they were both covering and woken up to find the young tyro helping to file his story to the paper. At the Guardian he worked in the features department alongside the future novelist Michael Frayn, vying to write the lead story on the paper’s miscellany page each day, for which they would be awarded an extra five shillings in their wages.

That was followed within a couple of years by a move to London to work on the Daily Express for double the salary the Guardian paid and then into television: initially for Granada, the independent station back in Manchester, working as a news reporter. Always ambitious and constantly on the move upwards looking for better money, soon there were programmes to present: the local news programme and later a weekly show about cinema.

When he finally left Granada he presented his colleagues with the key to his locked desk. Opening it when he had gone they found sheaves of blank hotel and restaurant receipts from all over the north of England, waiting to be used to cover shortfalls in expenses. It became known in the newsroom as the Parkinson bequest.

He also covered hard news stories, the Moors murders trial and, later, once he got to London, the Nigerian civil war and the Arab/Israeli six-day conflict for programmes such as World in Action and the BBC’s 24 Hours, though he ultimately decided he was not brave enough to be a war correspondent.

In 1971, he got his break with the Parkinson show, which ran for 11 years until in 1982 he was enticed away to become one of the launch team on the first breakfast news channel, TV-AM, alongside Anna Ford, Robert Kee, David Frost and Peter Jay. The launch was famously a disaster: its opening date postponed by the Independent Broadcasting Authority and then pre-empted when the BBC hurriedly launched a breakfast show of its own three weeks before they went to air.

Parkinson and his colleagues may have been well-known broadcasters, but they lacked managerial experience and the sort of populist touch needed for early morning shows and they were soon ousted.

Parkinson, drinking heavily during this period, left for Australia, where he had a chatshow.

He was not away for long and tackled his drinking habit with the support of his wife, Mary (nee Heneghan), whom he had married in 1959 after spotting her on the top deck of a bus – though he was so shy that he got a friend to ask her out on his behalf. Mary, then a fitness teacher, herself became a daytime television presenter for a time.

There were soon other programmes and documentaries, including a brief stint presenting Desert Island Discs following the death of its original presenter, Roy Plomley. There were also sports documentaries, presenting stints on other shows, on radio and television, and sports columns to write. “Parky” popped up everywhere, an instantly recognisable and genial figure as a broadcaster, though he could be testy with those sent by newspapers to interview him.

In 1998 came the revival of Parkinson. On his retirement from the show in 2007, Parky said that only two interviewees had evaded him: Frank Sinatra and the great Australian cricketer Sir Donald Bradman. Later, on the launch of his 2021 Jazz FM radio show, My Kind of Jazz, he said his hero Louis Armstrong was “the one man I really, really wanted to get on the talkshow …but eventually my good friend David Frost got the interview. I was so jealous; I could have killed him.”

Jazz and cricket remained his overriding interests in life. He settled in Bray, Berkshire, and continued to make one-off documentaries and published his memoirs, naturally entitled “Parky”, plus various spin-off books of interviews from his shows to add to an earlier biography of his friend Best and collections of his sporting journalism. He was often publicly critical of the state of television, blasting the “cult of youth”, and saying in 2009, “Please God, no more so-called documentary shows with titles like My 20-Ton Tumour … and The Fastest Man on No Legs”.

From 2012 to 2014 he hosted a Sky Arts Masterclass series.

Parkinson was appointed CBE in 2000 and knighted in 2008. He told the Daily Mail in 2012: “If I look back on my life, I took the monetary option when I often think I should have concentrated on my writing … I’d have been far poorer, but maybe more contented.”

Mary and their three sons, Andrew, Nicholas and Michael, survive him.

• Michael Parkinson, journalist and broadcaster, born 28 March 1935; died 16 August 2023

Yahoo News

Yahoo News