Will Catholics and Protestants ever heal their rift over Communion?

On February 29, for the first time in nearly 500 years, a Catholic mass was held in the main church in Geneva – the Protestant theologian John Calvin’s adopted home town.

It’s still not clear from news coverage whether Protestant worshippers were invited to receive communion. One report said that Protestants and Catholics alike would be invited to take communion while another denied this, insisting that: “people of a faith other than Catholic will not be formally invited to Eucharist, the sharing of bread and wine.”

The event, and the confusion around it, highlights the problem of some Christians excluding other Christians from this central sacrament of the faith – one that, rather than dividing Christians, ought to reconcile and unite. So, should – and can – Catholic doctrine change?

An illusion in most religions is that their beliefs and rituals are unchanging – and this is the same for most Christians. Instead of seeing the faith as dynamic, most Christians slip into thinking their particular focus of attention is not only immune to change but somehow perfect – the last word to be said on a topic.

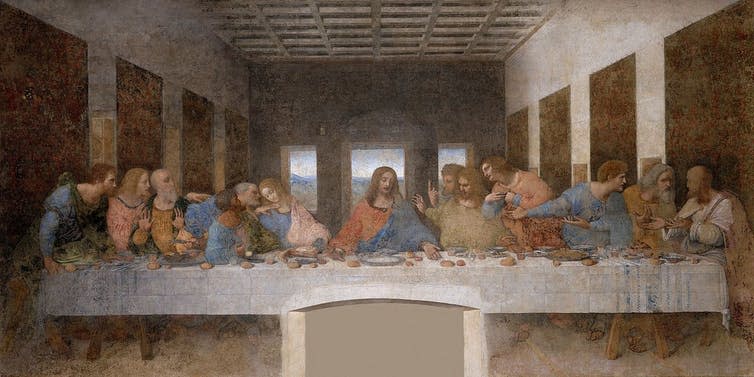

One item of doctrine that has got stuck in this way by being repeated rather than reflected upon is the Catholic Church’s statement that only those they consider in doctrinal agreement about the Eucharist (otherwise labelled as, variously, “Holy Communion”, “the Mass” or “the Lord’s Supper”) can participate fully at its celebration. This is a ritual whose symbolic focus is that of people gathered around a common table, eating portions of a broken loaf and drinking from a common cup filled with wine.

What each ritual element is taken to mean has been controversial for centuries – but the basic set of symbols seen as linked to the Last Supper of Jesus is common to all the churches. The various meanings given to this meal make it more a moment of visible tension between churches rather than the moment of coming together they all claim they want it to be.

Put crudely, this means that if you are a Protestant you are not invited to eat at a Catholic service. It also means that a Catholic, even if welcome at a Protestant Eucharist, should refuse to share fully in the meal by eating and drinking.

This practice of keeping denominations separate was standard policy for centuries – but, with the rise of the ecumenical movement in the 20th century, it began to seem out of place. Nonetheless, the Catholic Church – while willing to talk about unity – saw this step as impossible “until there was unity of faith”. By this the Catholics meant doctrinal uniformity: tantamount to a reversal of the Reformation – and there is no chance that will happen.

This no-go attitude on the Catholic side not only creates deep hurt in relations between church leaders, but it creates tensions in households every Sunday where partners want to worship together but one feels excluded if they are from differing churches.

Things could be different

This problem appeared to be easing after the Catholic Church’s Second Vatican Council (1962-5) which opened dialogues with the Reformed Churches to overcome inherited differences. But in recent decades, under two conservative papacies, the situation deteriorated again. In 1998 the Catholic bishops in Britain and Ireland issued (One Bread One Body) which effectively forbade any sharing of communion. Moreover, in a conservative climate it became clear there was serious resistance to discussion or research.

This negative climate was changed suddenly in November 2015. To mark the beginning of 500th anniversary celebrations of Martin Luther’s challenge to the papacy, Pope Francis visited Rome’s Lutheran Church . Afterwards, he took questions and this issue of intercommunion was, not surprisingly, raised. Rather than closing down the question, he opened up several new avenues of thinking which could lead to a change in Catholic law and practice.

Francis used his familiar approach that the church is more a field-hospital for suffering humanity than an oracular lawgiver. What, he wondered, if communion was food for a journey needed by people, rather than a reward for being a good Christian? This new openness will not be welcomed by conservatives, but many see it as a new way forward in relations between the churches.

Francis also called on theologians to explore this difficulty afresh. Here is the key statement:

Instead on the journey, I wonder – and I don’t know how to answer, but I make your question my own – I wonder: is the sharing of the Lord’s Supper the end of a journey or the viaticum [travellers’ food] to journey together? I leave the question to the theologians, to those who understand.

What would Jesus do?

So can one create a theological rationale for change? Here is just one such argument. We humans need food – but only through teamwork can we eat. We do not simply eat together, we share meals. Meal sharing is distinctively human – and this sharing has an inherent structure.

This has implications for the eucharist because its form is a meal – commemorating Jesus’s last supper. Can you be present and I refuse to share the food with you? Can I say that it is a meal of welcome and then not share with someone I call a “sister” or a “brother” because of Christian baptism, who asks for a share? Family meals must promote reconciliation by sharing or they are dishonest – and so unworthy of worship.

I have tried to take up Pope Francis’s call to theologians and advanced nine different arguments for a change in Catholic practice in my book Eating Together, Becoming One. They have only one common element: fixing this ulcer of division means re-imagining the meal Jesus bids his followers to share in his memory.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Thomas O’Loughlin’s book Eating Together, Becoming One: Taking Up Pope Francis’s Call to Theologians is published by Liturgical Press.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News