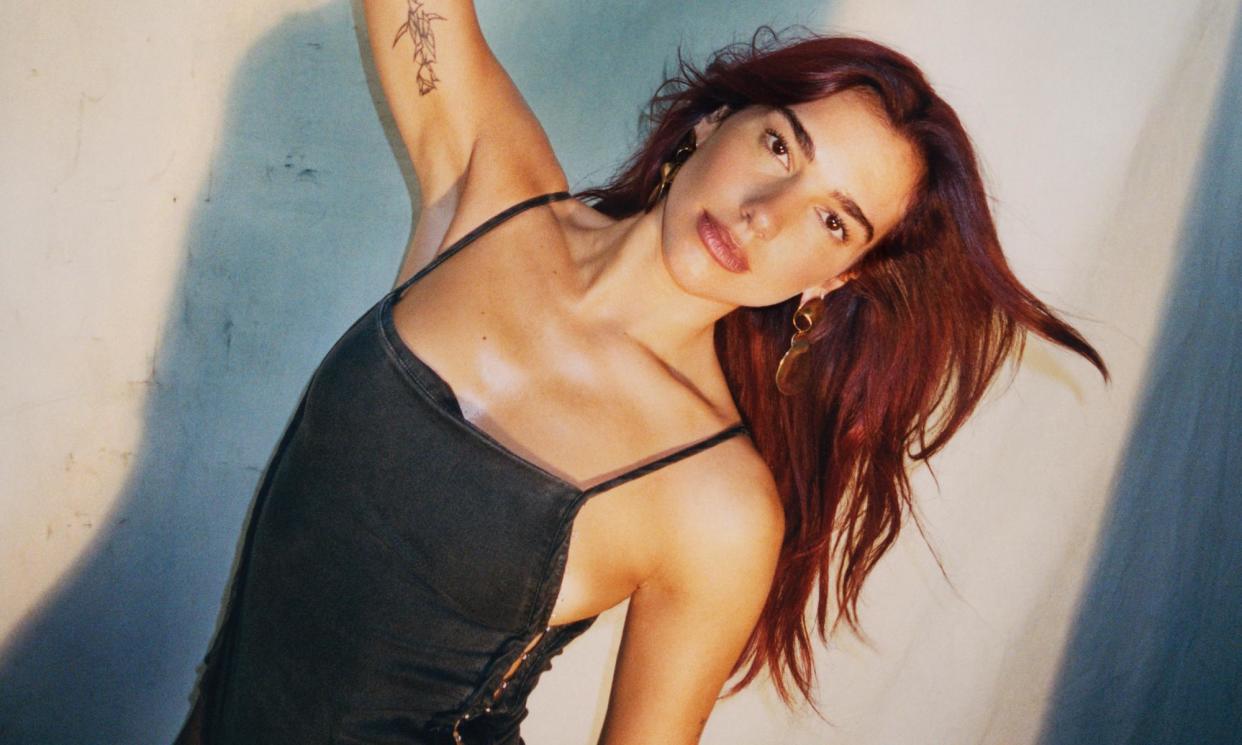

Dua Lipa: Radical Optimism review – ‘psychedelic pop-infused’? Pull the other one!

Earlier this year, Dua Lipa gave a lengthy magazine interview, the first salvo on the promotional trail for her third album. It wasn’t very interesting – she’s smart enough to keep her private life and her opinions on anything contentious to herself in a world of over-sharing and constantly simmering online outrage – but there was one surprising detail. She said the album was “a psychedelic pop-infused tribute to UK rave culture”, influenced by Primal Scream, Massive Attack and the “don’t give a fuck-ness” of Oasis and Blur.

That all sounds intriguing. It would clearly be a dramatic departure from the disco-house sound of 2020’s Future Nostalgia, while feeling curiously of the moment: all those artists reached their peak three decades ago, and 90s revivalism appears to be having a moment. A hankering after the era’s pre-9/11 optimism and pre-smartphone straightforwardness has meant Britpop references suddenly seem to be everywhere, as a recent feature in this newspaper noted. Perhaps, by delving into some corners of the 90s where mainstream 2024 pop seldom goes, Dua Lipa has made an album as inadvertently zeitgeisty as its predecessor which rocketed her into pop’s superleague by providing a soundtrack to lockdown-era kitchen discos.

Well, she hasn’t. In light of its advanced billing, it’s hard to listen to Radical Optimism without wondering what on earth its author is talking about. It sounds nothing like any of the artists mentioned, even less like a “psychedelic pop-infused tribute to UK rave culture”. Instead it sounds exactly like an album by Dua Lipa; the most surprising thing about it is probably the sound of the singer rapping, in cool RP tones, on opener End of an Era. If you were desperate to find references to pop’s past, you’d be better served abandoning your copies of Screamadelica and Blue Lines and considering instead the oeuvre of Abba, who haunt the melodies of These Walls and Falling Forever and the cascading, Dancing Queen piano line of Training Season. A more recent point of comparison might be Caroline Polachek’s Desire, I Want to Turn into You, which co-producer Danny A Harle also worked on: End of an Era carries some of the summery, flamenco-driven ambience of that album’s Sunset while French Exit applies a layer of gloss to the chattering rhythms of Bunny Is a Rider.

But it’s so far removed from what Dua Lipa has claimed it is that you find yourself frantically searching for evidence of what she might have meant. Does the “psychedelic” part refer to the presence of songwriter/producer Kevin Parker, who certainly started his career making lysergic alt-rock with Tame Impala, but turns up here in his pop hitmaker guise familiar from his work with Lady Gaga and the Weeknd? Is the regular presence of an acoustic guitar – and a pretty sliver of electric slide that decorates These Walls – supposed to signify Britpop?

You could drive yourself mad doing it, so perhaps it’s better to focus on what is here, rather than what isn’t. It’s sunlit and appealingly frothy – you could divine a lot from the fact that Radical Optimism was sent out to journalists under the pseudonym Candy Floss. That it lacks an immediately grabby pop anthem along the lines of Physical or New Rules doesn’t mean it lacks hooks: they’re just the kind that burrow under your skin without you noticing, as on singles Houdini and Illusion. Similarly, the production tends to subtlety: most of the sonic excitement happens in the lower end, in the busy acid lines that underpin Maria, the thunderous live drums of Falling Forever and the combination of slap bass and sprawling deep electronics behind Watcha Doing. Maria deals in Jolene-like love rivalry, Happy for You ends the album on a note of Someone Like You-ish passive aggression – the kind of song in which the protagonist professes at length to be delighted at how hot their ex’s new partner is, which means the album’s much-vaunted optimistic tone takes on a hint of a fixed grin – but for most part, the lyrics are of the type that rhyme “sweetest pleasure” with “gonna be together” and “this could be forever”, ie they seem to exist primarily in order to give the singer some words to sing rather than actually expressing anything.

In a way, that seems very on-brand. Dua Lipa’s refusal to engage with the more soul-bearing aspects of 21st-century celebrity has made her the kind of pop star one suspects Andy Warhol might have had a lot of time for: a slightly remote, visually arresting space into which fans can project whatever they want. Profile writers looking for an angle have recently suggested she’s everything from big-sisterly “agony aunt for lovelorn club kids” to a “dauntless warrior queen” to a sharp-eyed operator carefully plotting every part of her success. Being a blank slate has served her well thus far, although it’s seldom a strong long-term strategy, and Radical Optimism lacks a unique personality as a result – particularly compared with the vivid writing of her peers. It’s a well-made album with mass appeal and, of course, there’s no law that pop music has to be deep. But the adjective in its title certainly doesn’t belong.

This week Alexis listened to

Nilüfer Yanya – Like I Say (I Runaway)

Like I Say has an infernally catchy melody, but the sound is appealingly rough-edged: pop with dirt under its fingernails in a perfectly manicured world.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News