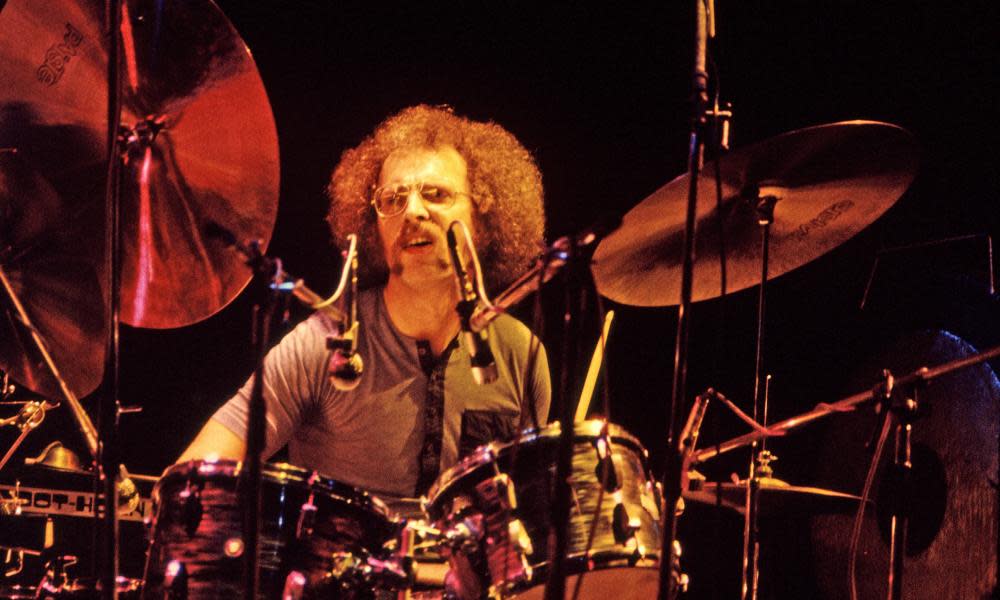

John Marshall obituary

The long career of the British drummer John Marshall, who has died aged 82, spanned a broad range of music. In one of his first recording sessions he was part of the anonymous band backing the Jamaican singer Millie Small on the song My Boy Lollipop, which reached No 2 on the UK and US charts in 1964. Later he would become recognised for his membership of several leading groups fusing jazz with rock, including Nucleus, Centipede and particularly Soft Machine, with whom his tenure spanned half a century.

A member of a new generation of gifted British jazz drummers emerging in the 1960s, alongside Tony Oxley, Alan Jackson, Trevor Tomkins, Jon Hiseman and Tony Levin, he showed an early facility for switching between the conventional 4/4 swing of modern jazz and the 8/8 rock rhythms that were beginning to permeate the work of younger improvising musicians.

That double fluency, blending the flow of the former with the more aggressive modernity of the latter, would stand him in good stead in a variety of contexts, from the German bassist Eberhard Weber’s quartet Colours to the great Canadian arranger Gil Evans’s British orchestra.

Born in the west London suburb of Isleworth and brought up in Hounslow, he was the elder of the two children of Stanley Marshall, the head hall porter in a private hotel in South Kensington, and his wife, Clare (nee Lummis), who was also on the hotel’s staff. A bright boy, he was moved up a year at junior school before attending Isleworth grammar school.

Since there was no family tradition of university education, he took and passed the civil service exam before spending 18 months at work in the Public Trustee Office. Encouraged by a girlfriend’s father, he applied to study psychology at Reading University, where the various student jazz combos provided an outlet for his love of music. His interest in the drums, which had begun at school, was developed through lessons with the percussion teacher Jim Marshall and the jazz drummer Allan Ganley.

After returning to London he studied with the American drummer Philly Joe Jones, who was then living in the UK, and in 1964 he briefly joined Alexis Korner’s Blues Incorporated, succeeding two previous incumbents, Charlie Watts and Ginger Baker. Soon he was undertaking session work and accompanying singers – including Salena Jones, Annie Ross, Sarah Vaughan and Elaine Delmar – at Ronnie Scott’s, while also taking a summer job with the resident band at the Butlin’s holiday camp near Filey, North Yorkshire.

His involvement in My Boy Lollipop came through Ernest Ranglin, the Jamaican guitarist who acted as musical director on the session. Two versions of the song were recorded on different days, one with another drummer, but Marshall was adamant that the take on which he played was the one that was released.

Young musicians on the London jazz scene were moving freely between each other’s groups, with Ronnie Scott’s Old Place, in Chinatown, as their informal headquarters. In 1966 Marshall joined the sextet of the bassist and composer Graham Collier, whose first album, titled Deep Dark Blue Centre (1967), received widespread praise. He was also working in small groups led by the trumpeters Harry Beckett and Kenny Wheeler, the saxophonist John Surman and the guitarist John McLaughlin, and in the big band of the trombonist and composer Mike Gibbs, a fellow alumnus of the Collier sextet, where he played with the bassist Jack Bruce for the first time.

It was no surprise when he became a founder member of Nucleus, a band launched in 1969 by the trumpeter Ian Carr, inspired by Miles Davis’s recent turn towards rock beats and textures. The keyboards player was another former Collier bandmate, now Sir Karl Jenkins and known today as the successful composer of orchestral and choral music.

At the time of the band’s debut he had just married Maximiliana (Maxi) Egger, a young woman from Munich who had arrived in London the previous year to improve her English while working as an au pair. Their wedding was celebrated with a party attended by many musicians at his large flat in north London, which he had shared with the bassist Dave Holland, who had left the UK to join Davis’s band.

Marshall stayed with Nucleus for two years, performing at the Newport and Montreux festivals and appearing on their early albums. In 1970 he also toured and recorded as one of three drummers with Centipede, the pianist and composer Keith Tippett’s 50-piece jazz-rock leviathan.

He left Nucleus in 1971 to join Bruce, who had achieved fame and fortune with Cream, appearing on the album Harmony Row (1971) as part of a trio completed by the guitarist Chris Spedding, another former member of Nucleus. A year later Marshall was invited to join Soft Machine, taking the place of Phil Howard, who had replaced Robert Wyatt, the group’s original drummer. In a musical equivalent of the ship of Theseus, the entire lineup changed frequently over the years, until no original members remained.

A winner of the Melody Maker poll for the best British jazz drummer in 1973 and 1974, Marshall lectured and gave drum workshops and clinics in the UK and Germany. In 2022, having announced his decision to retire, he made his final recordings with the current version of Soft Machine, released this year as an album titled Other Doors.

He is survived by Maxi and his sister, Janet.

• John Stanley Marshall, drummer, born 28 August 1941; died 16 September 2023

Yahoo News

Yahoo News