Mars' Ancient Face-Lift: Water Carved Planet's Features, Not Massive Volcano

The face of Mars has changed since the planet's younger days. Billions of years ago, rain or snow may have carved major valleys on Mars, just as the largest volcanic structure in the solar system was forming on the Red Planet, new research suggests.

Understanding how Mars has matured over the years could help explain other mysteries of the Red Planet, such as why vast ice deposits lie buried under the Martian surface far from its poles, scientists added.

Mars is home to Tharsis, the solar system's largest volcanic structure. This continent-size bulge near the equator in the western hemisphere of Mars is about 7.5 miles (12 kilometers) high and 3,100 miles (5,000 km) wide, and hosts giant volcanoes up to 100 times larger than any on Earth, the researchers said. [Photos of the Red Planet from Orbit]

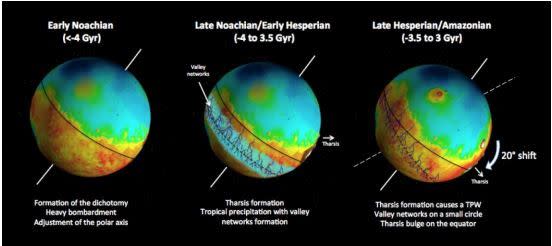

Previous research found that Tharsis started forming more than 3.7 billion years ago during the Noachian period. Prior work also found that its enormous mass — about a billion billion tons, or one-seventieth the mass of Earth's moon — was enough to pivot the outermost layers of Mars over the rest of the planet, a dramatic phenomenon known as "true polar wander," which caused the locations of Mars' north and south poles to shift.

Scientists previously found that many valleys on the Red Planet that formed by the end of the Noachian period more than 3.5 billion years ago were strangely oriented the same way as each other. The timing of the formation of these valleys and Tharsis suggested that Tharsis' effects on the hard rocky shell of Mars — its lithosphere — might have somehow influenced the directions in which these valleys ran, researchers said.

However, researchers now suggest that falling rain or snow helped carve these valley networks.

"We finally understand why the rivers formed where we see their dry beds today," the study's lead author, Sylvain Bouley, a planetary scientist at the University of Paris-Sud in Orsay, France, told Space.com.

The scientists carried out computer simulations to reconstruct how the Martian surface looked before, during and after the formation of Tharsis. They found that Tharsis would not have warped the Martian surface in ways that would explain the directions in which these valley networks formed.

To help solve the mystery behind the orientation of these valleys, the researchers noted that these valley networks occur in a band that runs around Mars. This circle is tilted with respect to the Martian equator.

The researchers suggest this circle of valleys originally lay parallel to and southward of the Martian equator. Their models suggest that substantial rainfall or snowfall in the tropical regions of Mars could have led to rivers that ran southward mostly parallel to each other, cutting valleys into the rock of Mars during the birth and growth of the Tharsis bulge. Later, during true polar wander, the position of this band of valley networks shifted, making it tilted with respect to the current equator of Mars.

These new findings suggest that these valley networks were born about the same time as Tharsis, instead of after Tharsis' formation, as previous research proposed. This in turn suggests that Mars' atmosphere was cold and substantially denser than it is today, which could have led to snowfall that helps explain why the Red Planet has giant ice deposits buried far from its poles, Bouley said.

The scientists detailed their findings online today (March 2) in the journal Nature.

Follow Charles Q. Choi on Twitter @cqchoi. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Copyright 2016 SPACE.com, a Purch company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News