Paraorchestra: Death Songbook live review – bittersweet ballads with Brett Anderson and friends

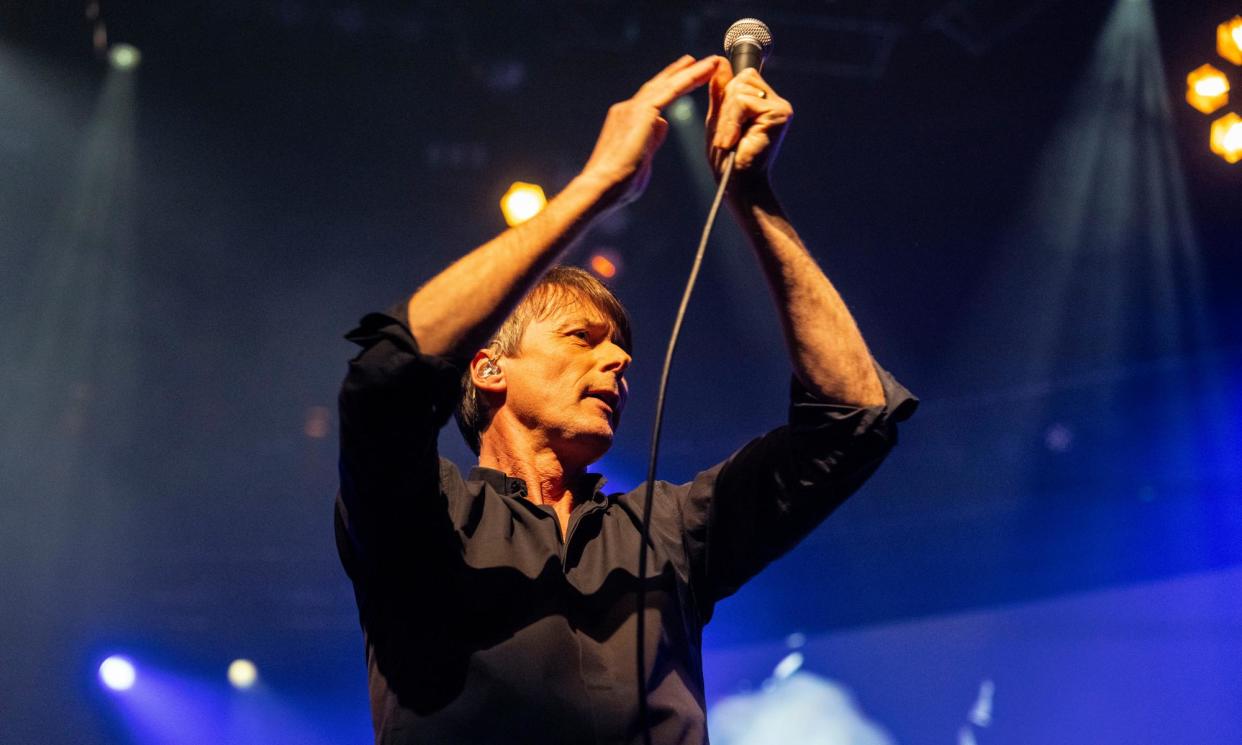

Dressed all in black, Brett Anderson is channelling the elliptical yearning of Echo and the Bunnymen’s 1984 song The Killing Moon. To his left, Paraorchestra percussionist Harriet Riley conjures a moody ache out of double-bowed vibraphone keys. Surfing atop currents of orchestral strings are flutes, whose trilling potential is kept in check here – this post-punk anthem requires a ghostly keen rather than anything more florid. On classical guitar, Paraorchestra’s Tony Remy is equally restrained, allowing himself some Spanish-tinged latitude only towards the end.

The Paraorchestra’s musical director, Charles Hazlewood, meanwhile, dapper of moustache, plays several instruments, often at once, and still has hands left over to lead the ensemble. It numbers 10 tonight, culled from the Paraorchestra’s “80 or 90” members, 50 of whom identify as disabled. This is an orchestra designed not only to break down ableist barriers, but also to dissolve the boundaries between orchestral music and the rest.

As well as tangling with the classical repertoire, the Paraorchestra has previously reimagined Kraftwerk and video game music. Its subtle, 3D take on Echo and the Bunnymen is a gateway track to what might double as a BBC 6 Music prom: songs people know, given a significant upgrade in dynamic range. Unprepared for an encore, the Paraorchestra and friends play The Killing Moon again at the end with the percussion dialled up.

Perhaps Nadine Shah nailed it when she trailed this performance as ‘a moment of melancholy magic with a bunch of fellow goths’

Originally performed in 2021 and 2022, Death Songbook is now an album. The project kicked off during lockdown when death was painfully foregrounded in the public imagination. Hazlewood and Anderson assembled a set of sweeping, bittersweet songs about death, or the death of love. The original sessions were socially distanced. Even in 2024, it remains poignant how far we have come, with woodwind players exhaling freely and Anderson clasping hands with Suede fans down the front. When he apologises for the lack of encore rehearsal, the excuse is a solid one – he’s been working on a new Suede record.

The tunes Anderson and Hazlewood, two fiftysomething men, bonded over were often from their youth in the 1980s, or from elsewhere in the indie rock canon. Japan’s Nightporter (1980) is here, sombre and resonant, as is Mercury Rev’s Holes (1998), on which Anderson is abetted by singer Nadine Shah, imperious throughout.

Central to the project are a handful of Anderson compositions. The Next Life, in which the then 22-year-old reflected on the death of his mother, remains one of Suede’s most emotional songs. She Still Leads Me On, from the band’s Autofiction (2022) is another, more mature look at that loss.

But next to these, Depeche Mode’s Enjoy the Silence feels like an outlier to the brief, dealing as it does with the limits of language in love. No one minds, though. Perhaps Shah nailed it when she trailed this performance as “a moment of melancholy magic with a bunch of fellow goths”. Death Songbook is dark-suited and Jacques Brel-loving, a place where dramatic emotion can legitimately overcome British reserve. Brel’s tune My Death finds Anderson, accompanied only by guitarist Remy, emphatically battling “the passing time” and channelling David Bowie’s and Scott Walker’s earlier renditions. It’s a stirring centre point.

In truth, though, Death Songbook feels like a slightly narrow take on the undiscovered country. These are great songs, played sensitively, but every track choice highlights paths not taken. The End of the World, for one, provides some much-needed female energy. Singer Skeeter Davis’s heartbroken 1962 plea to stop the clocks finds Welsh-Cornish singer-songwriter Gwenno trading regrets with Anderson while the Paraorchestra conjures a bittersweet waltz. Fabulously, Emma Coulthard gives voice to a large, freestanding contrabass recorder that looks as if it was hewn from Minecraft blocks.

Davis originally came from country music, a genre strangely absent from this project. The blues, too, are quite big on death and the death of love, as is folk music and soul. Other chansonniers pair sober tailoring with romantic pain: Nick Cave and Leonard Cohen, for two. Perhaps Anderson and Hazlewood wanted to avoid the obvious big guns. In a time of great conflict, this set feels somewhat apolitical. The reaper comes for us all, but power structures often disproportionately affect who goes when, and how and why.

Then again, it is perhaps unfair to expect one modest and elegantly formed undertaking to truly grapple with such a vast theme. The message of this sombre songbook is, perhaps, merely that sad songs say so much. The night’s most musically transporting passage, meanwhile, exhorts death to not be proud. The kaleidoscopic workout for Suede’s He’s Dead finds the Paraorchestra hitting a groove and tilting at the ineffable, its efforts underlining the importance of making a joyful noise while there’s still time.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News