Steam engines, injuries and a train called Brexit: The mad story of Lloyd Webber’s Starlight Express

In 1974, Andrew Lloyd Webber began working on songs for an animated TV series based on the Thomas the Tank Engine children’s books. It didn’t pan out, but the idea of singing, anthropomorphic trains would lay the foundations – or should that be the railway tracks? – for the 1984 debut of Starlight Express, the bonkers musical extravaganza in which actors don roller skates to whizz past the audience in a theatre refitted with a race track. Decked out in Eighties-meets-steampunk outfits, they play all-singing, all-dancing trains competing to be crowned the fastest engine in the world.

It’s enough to make its predecessor Cats look sensible and understated. Starlight Express has certainly been the butt of many jokes about the fever dream excesses of Eighties musical theatre – but it’s also a show that inspires diehard devotion (both semi-ironic and entirely sincere). During its first 17-year stint in the West End, it was seen by more than 8 million people and earned £140m at the box office. It has run since 1988 in the purpose-built Starlighthalle in Bochum, Germany, a venue that has held the Guinness World Record for most visitors to a musical in a single theatre since 2010. And, this month, Starlight Express is making an extravagant return to London, pulling into the Wembley Park Theatre and transforming this cavernous former television studio with ramps, runways and pyrotechnics.

Now that “immersive” is one of the biggest buzzwords in the theatre world, Starlight Express – with its performers deftly weaving through the audience at speed – seems less like a punchline and more like a trailblazer. But Lloyd Webber never envisioned the show to be quite so, well, flashy. After his Thomas the Tank Engine series failed to pick up steam (Granada TV, who had commissioned the pilot episode, thought that the stories didn’t have enough international appeal to justify the animation costs), he was hired on another train-related project. This time, a cartoon version of Cinderella, in which, for some reason, the fairytale heroine would be a steam engine (the ugly sisters, meanwhile, would run on diesel and electricity respectively).

Perhaps unsurprisingly, this was another false start. But when Lloyd Webber took his children to the Valley Railroad in Connecticut during a trip to the United States, their awed response to the old engines reaffirmed his intention to turn his dreams of a locomotive musical into a reality. “I’ll never forget Nick [his son’s] face when he saw a steam train coming,” the composer later told The Telegraph. “If you ever see a kid with a steam train, there’s something elemental about it.” He imagined the show as a concert for schools – just like the original version of Joseph and the Amazing Technicolour Dreamcoat – and joined forces with Richard Stilgoe, who had written lyrics for Cats.

The pair debuted a handful of songs at Sydmonton Festival, a theatre showcase held in the grounds of Lloyd Webber’s country estate, with the likes of Elaine Paige and Bonnie Langford on performing duties. Director Trevor Nunn, who had also worked on Cats, was in the audience. The material, he thought, was a little on the twee side, but he agreed to develop the show if he could amp up the sense of “theatre magic”. Seeking ways to turn a low-key children’s show into a real spectacular, they lighted on the idea of roller skating performers hurtling around a theatre space. At one point, Stilgoe recalled for The Guardian, the creative team ended up “stood in the ruins of Battersea power station, seriously discussing whether Andrew should buy the building to put Starlight Express on in it”. How different the power station’s regeneration might have been.

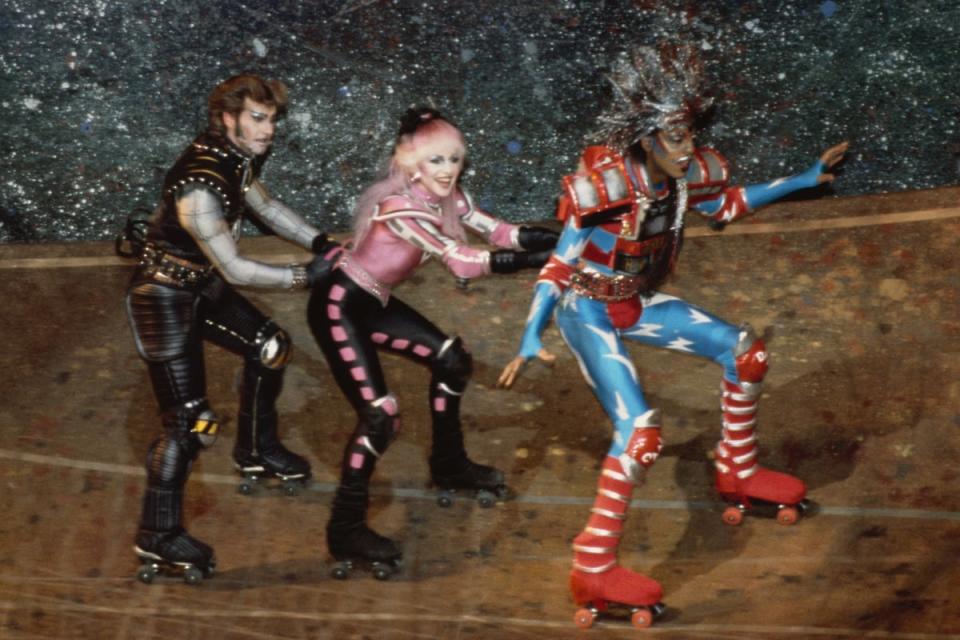

Arlene Phillips, who had previously learned to roller skate – at seven months pregnant, no less – while working on the Village People’s film Can’t Stop the Music, was brought on board to choreograph the complex, high-speed routines (performers would reach 30mph – no wonder the show would later acquire a reputation as one of the West End’s most injury-plagued productions). Designer John Napier would mastermind the set: it featured race tracks going all the way into the audience (including the upper tiers) at the Apollo Victoria Theatre, and a six-tonne steel bridge connecting different levels. No wonder it cost upwards of £2m to construct, making it the most expensive show in the West End at the time.

When the doors opened in March 1984, audiences were treated to a truly mind-boggling story. Steam engine Rusty is desperate to win the championship and be named as the world’s fastest train, despite his reliance on old-fashioned technology. He also hopes to impress Pearl, a first-class observation car, along the way. His competitors include a diesel train that also doubles up as an Elvis impersonator and an electric train who sings about bisexuality. There are plenty of other engines with smaller parts too, who are introduced through song (who could forget the freight trains who sing “freight is great”?) In need of some help, Rusty prays to the Starlight Express, a mythical train possessed with legendary speed. Oh, and there’s a disembodied child’s voice, known as Control, presiding over the whole thing.

Initial reviews were mixed: many critics thought an overemphasis on spectacle drowned out its emotional impact. The Guardian likened it to “a theatrical Star Wars, in which the human element is constantly struggling to get out”, while The Telegraph dismissed it as “only playing trains on a gargantuan scale”. But, as with so many musicals, a lukewarm response from journalists couldn’t diminish the ticket-buying public’s enjoyment of a show that really was like nothing the West End had seen before. By the end of the year, Princess Diana had graced a gala performance with her presence.

While most composers would probably draw a line under their involvement at this point, Lloyd Webber has been tinkering with the production ever since. Since its debut, it has been revised over and over again, with characters and songs being either removed or added in. Starlight Express is to musical theatre what Sugababes are to pop: its component parts are constantly being shuffled around. According to Lloyd Webber, the show “by its nature has to change”. He originally rooted the score in pop music to encourage young people to enjoy the theatre; music trends come and go, so Starlight Express must adapt accordingly. Sometimes characters simply undergo a name change: in 2017, the British train formerly known as “The Prince of Wales” was rechristened as “Brexit”.

The musical’s latest incarnation will also feature a brand new number all about hydrogen power. “I thought we can’t be saying that dirty [coal-powered] old steam trains are wonderful,” Lloyd Webber told The Telegraph. “There has been a lot of investment in hydrogen energy, and it occurred to me that instead of being nostalgic, we could have a show which suggests steam [courtesy of hydrogen] is the future.”

Commentary about renewable energy? If that sounds a bit heavy for you, fear not: even Lloyd Webber knows that Starlight Express is a show that it’s best not to take entirely seriously. As he once put it, Starlight Express is “meant to be nothing other than fun with a tiny heart of gold beating among all its trappings”.

Starlight Express is at the Troubadour Wembley Park Theatre, booking until 16 February 2025

Yahoo News

Yahoo News